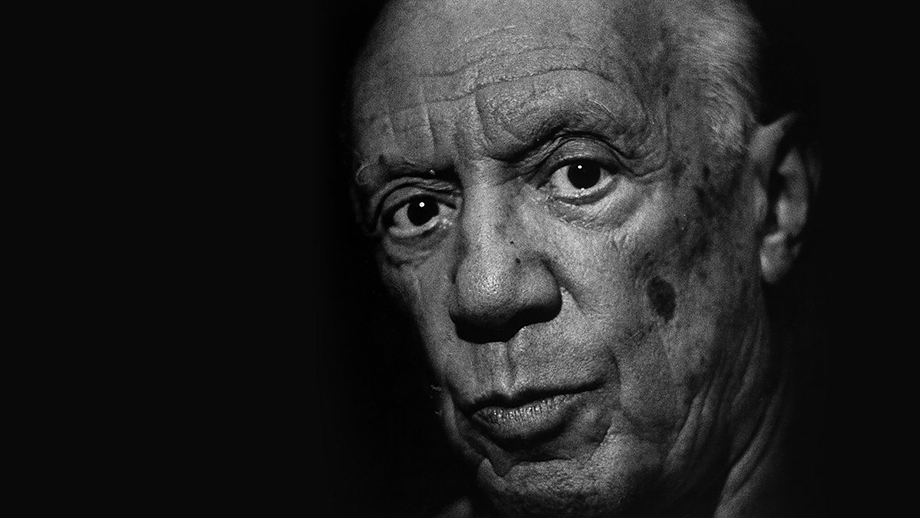

Picasso/Asia: A conversation

Picasso/Asia: A conversation, at M+ in Hong Kong, is simply splendid. It is innovative: not a standard chronological parade of ‘masterpieces’, but a rich and probing interrogation of the most famous European artist of the twentieth century, paired with an intelligent consideration of the impact of his work in Asia, and how it connected with Asian artists. The cover of the accompanying book shows a hilarious 2010 remaking by Japanese trickster Yasumasa Morimura of a famous 1952 photograph of Picasso by Robert Doisneau; it is playful, pungent, and undeniably affectionate, a dazzling example of curiosity among Asian artists about this towering figure. In fact, Picasso specifically addressed Asia only once, with the 1951 painting Massacre in Korea. More on that later.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.