At Eternity's Gate ★★★★

A man sits on a chair in a field, hands clasped together. He runs into the open grass before collapsing onto the ground. Grasping a handful of earth, he holds it high above his head and lets it fall over his face. He sits up, draws a palm across his mouth, and looks at the sunset. He grins.

Vincent van Gogh is an artist difficult to see clearly. Endlessly reimagined, the post-Impressionist is tucked inside myriad pockets of culture, from a Don McLean melody to a Tupac Shakur poem to a Doctor Who episode. In film, many have tried to encapsulate him. Kirk Douglas gives us a seminal Vincent in Vincente Minnelli’s Lust for Life (1956), setting a precedent for the painter as chaotic and impassioned. Tim Roth offers a Vincent similarly chaotic but more sinister in Robert Altman’s Vincent and Theo (1990), a take on the loving if turbulent relationship between Vincent and his brother, Theo. Most recently, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman pay homage to the art itself in Loving Vincent (2017), set after Vincent’s suicide and comprised of sixty-five thousand hand-painted frames.

It might seem bold, or inescapably recursive, to attempt another biographical study of the Dutchman. Yet At Eternity’s Gate, director Julian Schnabel’s tender portrait of the artist, succeeds for what it tries to eschew: another retelling of the life of Vincent van Gogh.

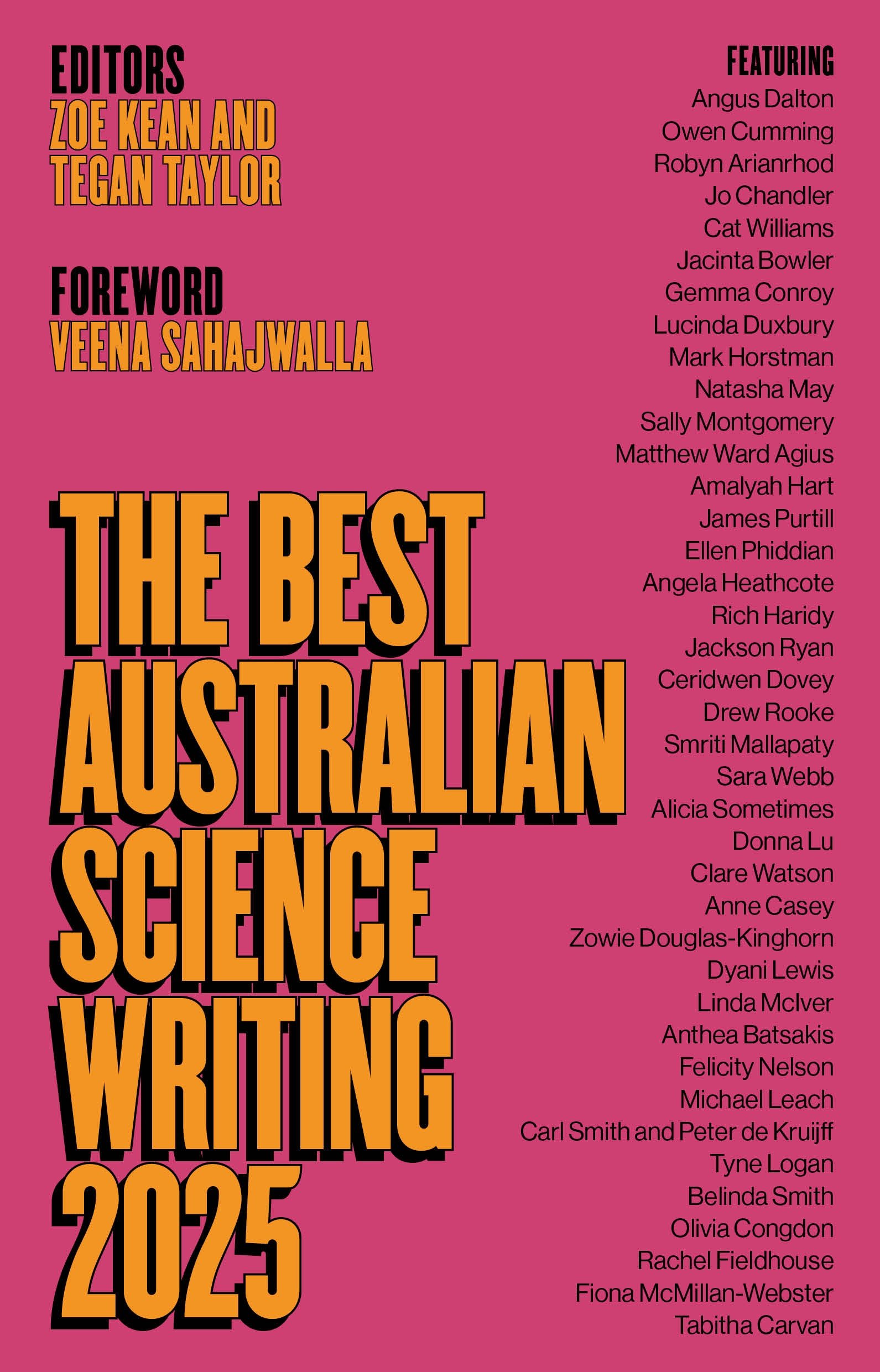

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity's Gate (photograph via CBS)

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity's Gate (photograph via CBS)

The film, in a series of unreliably chronological vignettes, looks at Vincent’s final years before his suicide in 1890. We first encounter the painter (Willem Dafoe), creatively and emotionally weakened, in a freezing Paris with Theo (Rupert Friend). Uninspired and seldom painting, he heeds the words – ‘Go south, Vincent’ – of a French painter he meets, Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac). From Paris, he travels to the sun-kissed fields of Arles. We walk with him, cane in hand, feet trampling reeds, legs carving swathes through wheat fields. In Arles, Vincent finds a home in the abandoned 2 Place Lamartine, the famed Yellow House along the Rhône River. Gauguin soon joins him, and together they enter a period of mutual productivity, challenging each other on the true nature of art. The majority of the film is set here, in Arles, where Vincent entered the most creatively fecund but increasingly volatile time of his career.

As van Gogh, Willem Dafoe evokes an artist both intimidating and vulnerable. From his previous roles – a career ranging the humble Judean carpenter in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), the terrifying Green Goblin/Norman Osborn in Spider-Man (2002), and the world-weary Bobby in The Florida Project (2017) – we know Dafoe as a master of expression. Whereas Douglas, Roth, and Dutronc portray a manic yet steely-eyed Vincent, Dafoe’s van Gogh is almost a frightened animal: one moment frenetic, the next self-doubting, frightened, assailable. His performance is one of unrelenting unease, one reifying the struggle Vincent had with his art and, inextricably, his health. Yet Dafoe also captures his tendency to frighten and intimidate. Despite the age difference between actor and painter (Dafoe at sixty-three, Vincent thirty-nine when he died), there is no feeling of detachment. If anything, Dafoe’s weathered mien, taut skin, and weary eyes convey a prolonged anguish and sensitivity, as well as a fearsome instability.

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity's Gate (photograph via CBS)

Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity's Gate (photograph via CBS)

Julian Schnabel, a distinguished painter himself, has dissected artists and their methodology before. In Basquait (1996) he tells the poverty-to-painter tale of American postmodernist Jean-Michel Basquait, and in Before Night Falls (2000), the moving life story of Cuban writer and émigré Reinaldo Arenas. (Schnabel is most celebrated though for his depiction of stroke-victim Jean-Dominique Bauby in the multi-award-winning The Diving Bell and the Butterfly in 2007). The painterly care with which Schnabel and his cinematographer, Benoît Delhomme, treat colour, light, and shadow is apparent. Throughout the many scenes of Vincent meandering around the countryside – mostly to Ukrainian Tatiana Lisovkaia’s haunting score of discordant piano – the light of dusk turns green fields to turquoise, Vincent’s pale skin to shades of purple and blue. In one scene inside a church, Gauguin tells Vincent he is leaving Arles, the relationship between them having deteriorated. Vincent, left in despair that will culminate in the severing of his left ear, runs into the courtyard and is engulfed by the darkening indigoes and violets of twilight.

These scenes are largely viewed through Vincent’s perspective, with the camerawork shot entirely in hand-held, first-person perspective. Faces are oppressively close, the minutiae of stubble, eyelashes, and freckles becoming, as Schnabel describes, like the ‘portraits themselves’. The fractured nature of these vignettes effects upon the viewer an accumulative feeling of the painter, rather than a simple biography of his life. It is as if we embody Vincent: running through fields, brushing tree branches aside with outstretched arms, stabbing at the canvas with our brush.

Oscar Isaac as Paul Gauguin and Emmanuelle Seigner as Madame Ginoux in At Eternity's Gate (2018)

Oscar Isaac as Paul Gauguin and Emmanuelle Seigner as Madame Ginoux in At Eternity's Gate (2018)

The only hindrance to At Eternity’s Gate is its clunky dialogue. Scenes of Vincent and Gauguin sparring with platitudes about creativity quickly stale (‘it’s called the act of painting for a reason!’). However, there are inspired moments, such as when Vincent, admitted to the Saint-Rémy asylum, sits down to discuss his health with a priest (played superbly by Mads Mikkelsen). ‘I don’t want to hurt your feelings,’ the priest says, asking Vincent to look at a painting of his, ‘but don’t you see this painting is unpleasant? It’s ugly.’ The artwork, Landscape with Rabbits, now sits in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

‘I didn’t want to make a movie about Vincent Van Gogh,’ Schnabel says in an interview. This is clear. Schnabel doesn't want us to observe Vincent, he wants us to become him, to empathise with a man so inexorably tethered to nature and to light. ‘The winter is always dangerous to you,’ Gauguin wrote to van Gogh on 20 March 1890, a few months shy of his suicide. In At Eternity’s Gate, we come to appreciate the weight of those words.

At Eternity’s Gate (Transmission Films), 111 minutes, is directed by Julian Schnabel and is in cinemas from 14 February 2019.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Copyright Agency's Cultural Fund and the ABR Patrons.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.