Anna Bolena (Opera Australia) ★★★★

Opera Australia – in its present expansionary phase – has hitched its wagon to a digital star in the form of a series of seven-metre-high LED screens. The future moves about on a busy automation system, thus creating a series of new dramatic spaces. Interviewed in the July 2019 issue of Opera magazine, Lyndon Terracini – now in his tenth year as artistic director – extolled the new technology: ‘We’re choreographing the screens – essentially they become another character … You can fly them out, send them upstage or downstage, turn them at any angle … What we’re doing is much more progressive than anyone else.’

Like it or not, we’ll have to become accustomed to this bright aesthetic, for the company’s clearly not for turning. While rightly praising David McVicar’s production of Così fan tutte, recently seen in Melbourne (‘the most beautiful Così in the world’, according to Terracini), he was emphatic, in the same interview, that the future looks very different. ‘We’ll keep [Così] – and others. But over the next ten years, as we add new productions, they’ll be digital.’

The aim, he says, is twofold: to find new audiences (‘Aida attracted a lot of digital freaks who were new to art form’) and to save money (lots of it, presumably) on building sets. Next year’s Ring cycle – lost to Melbourne because of major works at the State Theatre commencing in 2020 – will be similarly digital when it moves to Brisbane: a new production to be directed by Chen Shi-Zheng.

The cast and chorus of Opera Australia’s 2018 production of Aida at the Sydney Opera House (photo by Prudence Upton)

The cast and chorus of Opera Australia’s 2018 production of Aida at the Sydney Opera House (photo by Prudence Upton)

It will be interesting to see how traditional opera audiences – and the favoured directors – cope with this LED technology. In the right hands, it might be transformative, as radical in a way as Wieland Wagner’s regenerative postwar productions of his grandfather’s soiled operas – a stripping away, a moving on, a veritable shaking up. In less confident hands – used glibly, gaudily, gratuitously – it has the potential to subvert the music and libretti that sustain our fascination with the hundred- or two-hundred-year-old operas that dominate this company’s repertory.

With new productions of Anna Bolena and Madama Butterfly (Graeme Murphy’s mixed affair), Sydney audiences currently have two opportunities to assess the merits of the digital technology, which had its début in 2018 with David Livermore’s production of Aida. Reviewing it, I remarked: ‘Only Enobarbus could do justice to the infinite variety of the Italian director’s busy production. It relies heavily on video, ten LED screens, comely gym-gods in G-strings, and inevitable hieroglyphics. There is so much going on in the first hour as to be giddy-making. Nothing, no one, stays still for more than ten seconds.’

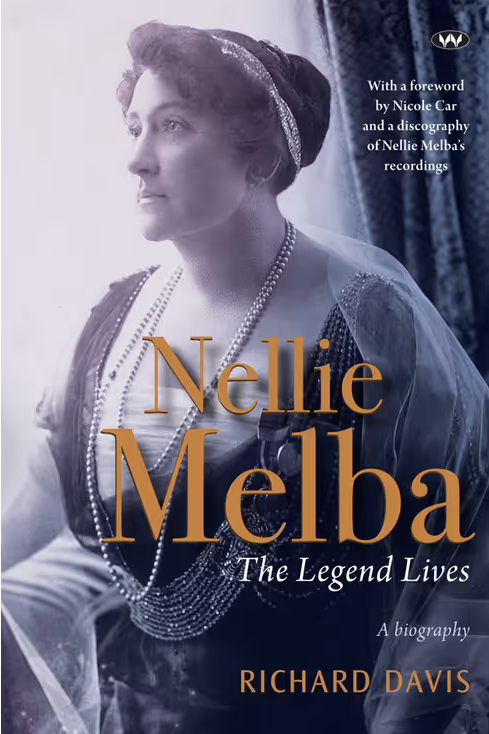

Livermore returns for the first in a series of Gaetano Donizetti operas: Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, and Roberto Devereux – each one to be directed by him. It’s been done before in Australia, quite recently: Melbourne Opera presented the Tudor trilogy between 2015 and 2017. It’s rare, though, for one soprano to tackle all three vocally and histrionically demanding roles. Beverley Sills did so in 1974 for the New York City Opera; Sondra Radvanovsky sang all three roles at the Met in 2015–16. (Melbourne Opera had two different queens: Elena Xanthoudakis as Anne Boleyn and Mary Stuart; and Helena Dix as Elizabeth in Roberto Devereux.) Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho, first up as Anne Boleyn, will not sing all three roles in Sydney.

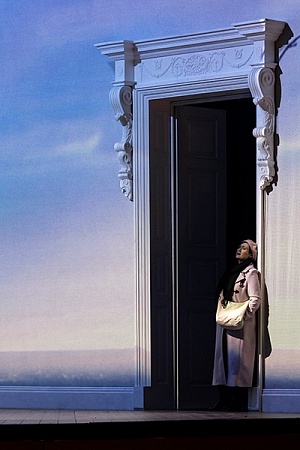

Ermornela Jaho as Anna Boleyn in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Anna Bolena at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Ermornela Jaho as Anna Boleyn in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Anna Bolena at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

The thirtieth of Donizetti’s seventy operas, Anna Bolena premièred at the Teatro Carcano in Milan on 26 December 1830 (a full sixteen days after its completion). It was Donizetti’s first major international success. Writing to his wife after the première, he rhapsodised: ‘Success, triumph, delirium – it seemed that the public had gone mad. All say that they do not remember ever being present at such a decided triumph.’

Anna Bolena soon moved to London and Paris, with the same principals, Giuditta Pasta (Anna) and Giovanni Battista Rubini (Percy). Donizetti had written the title-role for Pasta, the first Amina and Norma, of whom Stendhal wrote, she ‘electrified the soul’. Interestingly, Pasta’s singing was said to be ‘chaste and expressive’, ‘never disfigured by meretricious ornament’ – ‘The crowning excellence of her art was its grand simplicity’. This stateliness and expressiveness surely influenced the creation of Donizetti’s heroine (the first of his Tudor queens).

Anna Bolena was performed throughout the nineteenth century, but verismo opera brought an end to that at the turn of the century and it was not revived until 1956 (in Bergamo, Donizetti’s birthplace). A year later, Luchino Visconti emphatically restored it to the repertory with a famous production at La Scala, which was revived the following year. The opera (though it has been performed by the likes of Montserrat Caballé, Edita Gruberová, Anna Netrebko, and Joan Sutherland, rather late in her career) will forever be associated with Maria Callas, notwithstanding the fact that she performed it only twelve times, and only in Milan. The sole ‘full’ performance we have is a live recording from La Scala on 14 April 1957 (egregiously cut though it was by conductor Gianandrea Gavazzeni, who had seen it in Bergamo and brought it to Milan for Callas; ‘butchery’ was how Andrew Porter described it). This was one of Callas’s most blazing and vocally even performances since her Lucia with Karajan in Berlin two years earlier. For lovers of bel canto singing, it is an indispensable recording, like the mad scene she recorded the following year. Callas, throughout, while battered and disbelieving, is always queenly, befitting Anne Boleyn’s exalted status (Anne was, after all, crowned with the same crown as the reigning monarch – a unique honour – making her, in effect, Queen Regnant).

Ermonela Jaho as Anna Boleyn and Leonardo Cortellazzi as Lord Percy in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Anna Bolena at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Ermonela Jaho as Anna Boleyn and Leonardo Cortellazzi as Lord Percy in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Anna Bolena at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Felice Romani’s libretto is based on two plays: Anna Bolena by Alessandro Pepoli (1788) and Marie-Joseph de Chénier’s Henri VIII (1791). This was their third collaboration, and the first time Donizetti had been presented with a first-class text. (Romani later wrote the libretti for L’elisir d’amore and Lucrezia Borgia.)

Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s second queen, needs little introduction. Her story, fancifully told here, is very familiar. The opera begins in medias res. Anne, shattered by her husband’s unfeelingness, doesn’t realise that Jane Seymour, her lady-in-waiting, is his new paramour. Mark Smeaton, the queen’s page, is a gauche, flirty complication, and when Anne’s old admirer Lord Percy returns to court, Henry seizes the opportunity to accuse her of adultery with practically any male in her circle, including her brother, Lord Rochfort. Anne is duly tried and condemned. The opera – performed here without cuts, thus running for more than three hours – ends with an arresting mad scene in the Tower of London prior to her decapitation.

From the beginning, everything is tremulous, everyone apprehensive. Jeremy Commons writes in the Decca/Bonynge booklet: ‘Right from the moment when the curtain rises … right from the moment when we hear the violin figure of the Introduction, with its unsettling tremolo on every note – we are struck by a sense of foreboding.’

Ermonela Jaho, in the title-role, is a natural foreboder, ever mannered and tragic. Interviewed in the June 2019 issue of Opera magazine, Jaho said: ‘We are so naked on stage in opera. We can’t fake it. You need to be human, to be real. Singing is vocalizing your soul out.’ At times it was like watching a stricken martyr from the silent era.

Jaho has sung here once before, in 2017, as Violetta (she has performed the role 250 times in about thirty productions of La Traviata around the world, including recent performances at Covent Garden). Hers is not a big voice, and there was less of it for a while after that demanding first act, which culminates in a phenomenal outburst from Anne when she is arrested: ‘Giudici, ad Anna’. With considerable artistry and enormous commitment, Jaho husbanded her voice and met all the challenges of this taxing score. The scintillating duet with Jane Seymour – when Anne finally recognises that her lady-in-waiting is her rival – won a long ovation. Carmen Topciu, impressively carnal at times despite her seeming contrition, was a powerful presence throughout; her mezzo soprano is much stronger than Jaho’s careful, filigreed soprano.

Anna Dowsley as Mark Smeaton, Carmen Topciu as Jane Seymour, Teddy Tahu Rhodes as King Henry VIII and Ermonela Jaho as Anna Boleyn in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Anna Bolena at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Anna Dowsley as Mark Smeaton, Carmen Topciu as Jane Seymour, Teddy Tahu Rhodes as King Henry VIII and Ermonela Jaho as Anna Boleyn in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Anna Bolena at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Anne’s long aria in the Tower, Donizetti’s first great mad scene for soprano, is one of the finest things in bel canto opera. Winton Dean considered it ‘a masterpiece of dramatic pathos’, much better than the ‘conventional and far inferior’ mad scene in Lucia di Lammermoor. The scene comprises a series of short arias. The aria based on Henry Bishop’s ‘Home, Sweet Home’ gives the final scene great character. Anne, delirious, drifts in and out of consciousness, ‘lost [as Commons writes] in the labyrinths of a wandering, wavering mind’. Here, Jaho was at her best. ‘Al dolce guidami’ was beautifully preluded by the cor anglais. Jaho, lying on her back near the edge of her stage, sang with delicacy and pathos, all the trills and melismas impeccably placed.

Of the other singers, Anna Dowsley stood out as Mark Smeaton. Dowsley, who made such an impression as Dorabella in Melbourne, is fast becoming one of the stars of this season. Her opening song in the first scene, and the aria ‘Ah, parea che per incanto’ in the third, were superb. Leonardo Cortellazzi, though not always helped by some wayward lighting (John Rayment), sang freely and ardently as Percy; he was at his best in the Act I duet with Anne that signals their undoing, and in ‘Vivi tu’ in Act II. Richard Anderson and John Longmuir were fine as Rochfort and Hervey. Teddy Tahu Rhodes, physically menacing as Henry, sang throughout with lots of volume but scant focus.

As for Livermore’s production, it is more measured than his Aida, but not always convincing. It opens with images of present-day London (Norman Foster’s Gherkin even) repeatedly scaled back to humbler Tudor times. Because something must always be done to enliven a mere overture, four dancers dressed in white rotated on the ubiquitous revolve, miming in vague allusions to facets of Anne’s tragedy. One even took touristic selfies, fast becoming a tired trope. Princess Elizabeth, absent from Romani’s libretto, appeared mutely, slightly too old and dressed, oddly, like a Velázquez Infanta – only to be snubbed by her imperious mother and finally, huffily, to snub her in retaliation.

Mostly the LED screens were filled with brilliant amber or wrought iron on which tiny beetles crawled up and down for all three hours, symbolically or not. The stage was very dark, and the brilliant costumes and wigs (Mariana Fracasso) accentuated this menacing gloom, apart from Henry’s Elvis Presley-like white outfit.

Renato Palumbo drew fine playing from the orchestra, and the chorus was in excellent voice.

Lastly, a note on a further departure at Opera Australia: this one quite regrettable. No longer does the company offer a substantial program for sale. Gone are the artists’ biographies, any serious expression of directorial intent, substantial synopses, essays on the opera, notes on past Australian productions, commemorative photographs, lists of donors, etc. Presumably, this represents another welcome economy, but how are amateurs and operatic newcomers meant to cope without any guidance? Surely Opera Australia – handsomely subsidised by Australian taxpayers and charging high prices – should do better than the flimsy leaflets currently on offer. Modern opera, if it’s to have a future, needs informed audiences, not just dazzled ones.

Correction: In an earlier version, we stated that Ermonela Jaho would undertake all three roles in Sydney. This was based on a separate report. Opera Australia informs us that the roles will be shared.

Anna Bolena continues at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House, until 26 July 2019. Performance attended: July 2.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.