William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen

2008_Artist_001.jpg)

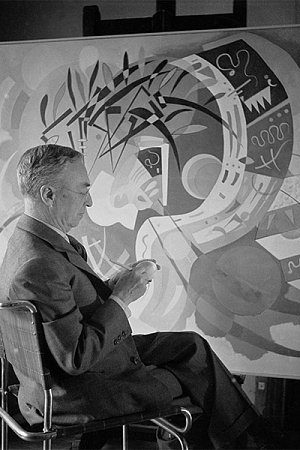

With its title, William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen, an exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery, signals two prongs of the politics of vision: the power of the gaze and the importance of representation, an apt framing for an artist who has been invested in both for more than fifty years. As a substantial and generous retrospective, curated by Rosie Hayes, it threads together the distinct but connected themes of Yang’s practice: queerness, particularly the queerness of gay men; Chinese-Australian identity and experience; the Australian landscape; and the art, film, and literary scene in Sydney.

One of the first works in the exhibition is a clip from Yang’s monologue-cum-film Sadness (1999, directed by Tony Ayres), displayed on a small monitor among framed photographs. Throughout the space, Yang’s voice can be heard recounting the experience of being taunted as a young boy in the late 1940s. He repeats a racist chant familiar to me from the playgrounds of my own childhood in the 1990s. The work in this first room represents his family and early life in the Atherton Tablelands of North Queensland. Across the show, Yang’s treatment of his heritage treads complex ground. A black-and-white photo of Yang with his two siblings, all in costume, is accompanied by text explaining they were raised ‘in the Western way’; his mother thought that ‘being Chinese was a complete liability’. This was a loss for Yang – work in an adjacent gallery documents his efforts to reclaim Chinese culture. Nor did it protect him from racism. In one of the many self-portraits in the exhibition, Yang is pictured at the site of his uncle’s murder in 1922. Part of the series My Uncle’s Murder (2008), Yang is dwarfed by the tall stalks of a sugar cane plantation. He wears a white T-shirt with Chinese script running down it. The small house where William Fang Yuen was killed is gone, but Yang stands in the violent legacy of his death.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.