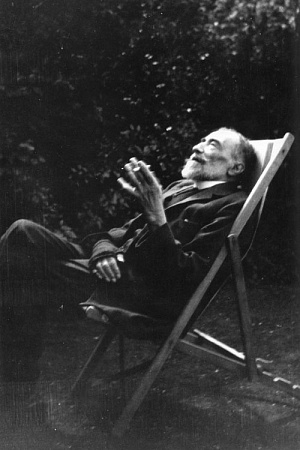

James Joyce in Australia

If James Joyce had ever visited Australia it is unlikely that he would have come up with anything like D.H. Lawrence’s Kangaroo. For one thing, as with most Irishmen, his interest in landscape was negligible; for another, his sense of play and his myopia would not have allowed him to romanticise the great Australian bush, much less the suburban sprawl. He might have felt somewhat at ease in the ‘Loo or the Rocks area, in Gertrude Street, Fitzroy or Little Dorritt Street in Carlton, or perhaps by the Yarra at Burnley. But why fantasise? The man who had to scrounge and borrow to pay his fare from Dublin to Trieste, who lived most of his life in extreme poverty and on handouts from friends, could not have afforded the passage to Australia, even had he wished. (He did, however, once apply for a job with the South African civil service.) Of his three major (and dozens of minor) money-making schemes – busking at the seaside resorts of England, establishing the first cinema in Dublin, and securing the Donegal Tweed licence for Trieste – only the latter came to reality and, to his surprise, few of the denizens of that polyglot city rushed to bedeck themselves in Irish tweed. Joyce, it appears, was not much of a traveller, a businessman, or an economic genius.

Yet Joyce did come to Australia, and in a form different from his appearance elsewhere in the Western cultural world. He came here, of course, in one of the forms he playfully chose – as instigator of scholarly theses on his works, and hence as a serious progenitor of many fine academic careers. But his most obvious showing was in a form which he himself had deliberately discarded as part of his juvenilia – that of Stephen Hero.

Joyce’s rejection of this his earliest alter ego in favour of Stephen Dedalus indicates the quantum leap in his work from writer to artist. Stephen Hero (or that part of him which remains in the incomplete manuscript left to us) is, as the name suggests, the romantic martyr-hero. He is a loosely veiled adolescent Joyce, serious, pompous, self-important. His crises – those with his religion, his family, and his nation – are worried through with intensity of rhetoric and a pretence at high drama. His self-regarding concentration is almost priapic, and his martyr-hero stance is narcissistic in the worst traditions of romanticism.

Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is the transitional alter ego between Stephen Hero and the Stephen Dedalus of Ulysses. He is the young man, the learner, much more like the brash, gormless Icarus than the crafty, sagacious Dedalus. But he is the artist as a young man, whittled and shaped into being by Joyce the author, who portrays him with irony and gentle, loving humour.

Stephen Dedalus entered Australia mainly through university syllabi, and his entrance coincided with the great influx of Irish-Catholic youth into the Universities in the 1950s and early 1960s. For example, for various socio-political reasons, the major topic of interest to students at Melbourne University during this period was religion. Lunchtime debates on The Existence of God could draw between 500 and 600 participants, and the Catholic intellectuals of the time, Vincent Buckley, Max Charlesworth, Bill Guinnane, Paul Simpson, Jim Griffin, Peter Wertheim, John Ryan etc., were intent on showing the conservative Catholic establishment, as well as the secular institutions, that religion could be the Benzedrine of the masses.

It is not surprising then that Stephen Dedalus should have become something of a prototype artist-hero to many of the younger generation of Catholic students. After all, he was sensitive, serious, intellectual, brilliant, and he fought against the complex web of Catholic upbringing, family, and nationalism to win artistic freedom and independence. Joyce’s novel portrays him standing up bravely against the brutal and unfair punishment meted out on him by his teachers, suffering and tormented by the brilliant rhetoric of the sermon on hell and tearing himself free from the belief system into which he was born. To many young Catholics brought up in the close-knit web of Catholic school, parish and family social life, and DLP politics, the university represented a kind of religious, sexual, and intellectual freedom that was difficult to combat. Protective groups, such as the Newman society, attempted valiantly to demonstrate that students could maintain and develop their faith within the fierce secular atmosphere, but that most famous and widespread of Irish institutions, ‘the Split’, soon fragmented the protective group spirit, and by the mid to late 1960s the fervour once reserved for religious debate had shifted to the political sphere. About the same time, the ‘Catholic upbringing’ novels started to appear, and were warmly welcomed by the Australian reading public, since they confirmed several strongly held prejudices: that Catholic schools were brutal and insensitive; that Catholic attitudes to sex were distorted and unnatural and that to free oneself from the bonds of Catholicism was a remarkable and heroic feat achieved only by individuals of the Ubermensch variety.

In Stephen Hero, the young Joyce delivers his recantation of faith in the following conversation with Cranly.

- Then you do not believe any longer?

- I cannot believe.

- But you could at one time.

- I cannot now.

- You could if you wanted to.

- Well, I don’t want to.

… I am a product of Catholicism. I was sold to Rome before my birth. Now I have broken my slavery but I cannot in a moment destroy every feeling in my nature. That takes time. However, if it were a case of needs must – for my life, for instance – I would commit any enormity with the Host

… If I mum it is an act of submission, a public act of submission to the Church. I will not submit to the Church.

- You could be a rebel in spirit.

- That cannot be done by anyone who is sensitive.

Cranly here acts as a concerned friend seeking devious ways whereby Stephen can hold his views, but not cut himself off dramatically from friends, Church, and family. Stephen resists these blandishments with a stem display of heroic will, sensitivity, and honesty. The situation is serious and earnest.

In Portrait of an Artist, the discussion between Stephen Dedalus and Cranly is long and wide-ranging. Cranly acts as an older, tougher and wiser friend, and his comments on Stephen’s remarks are amicable but consistently mocking.

(Cranly) What are our ideas and ambitions? Play. Ideas! Why that bloody bleating goat Temple has ideas. MacCann has ideas too. Every jackass going down the roads thinks he has ideas.

Stephen, who had been listening to the unspoken speech behind the words, said with assumed carelessness:

Pascal, if I remember rightly, would not suffer his mother to kiss him as he feared the contact of her sex.

- Pascal was a pig, said Cranly.

- Aloysius Gonzaga, I think, was of the same mind, Stephen said. And he was another pig then, said Cranly.

The church calls him a saint, Stephen objected.

- I don’t care a flaming damn what anybody calls him, Cranly said rudely and flatly. I call him a pig.

Joyce’s use of Cranly, the intelligent, mature, honest friend able to mock, argue, cut down to size, is a masterpiece of invention in his portrait of Stephen. Cranly’s presence helps us place Stephen and his youth in the context of irony and humour, whilst not allowing us to condemn him utterly as immature and pompous. In Stephen Hero, the bantering and the chiack of Cranly are missing. Similarly such contextual means of distancing ‘the hero’ are absent from our Australian novels of Catholic upbringing. When humour is attempted in the general context of the novel such as in Barry Oakley’s A Wild Ass of a Man, it is singularly lacking in those actions which deal with the crisis of faith or the influence of the Catholic Church. What we have is a kind of savage bitterness and a sense of heroic achievement in the struggle to cast off the evil wrappings of a distorting belief system.

James Joyce did visit Australia and made a kind of permanent home here. But he did so in a form which he himself saw as immature, romantic and essentially silly and humourless. That form is the form of Stephen Hero – a young man who wanted to be and was trying hard to be an artist, but who remains for all time just a young man, trying to be an ex-Catholic.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.