The Whitlam Government 1972–1975

Viking, $35 pb, 787 pp

The Whitlam Government 1972–1975 by E.G. Whitlam

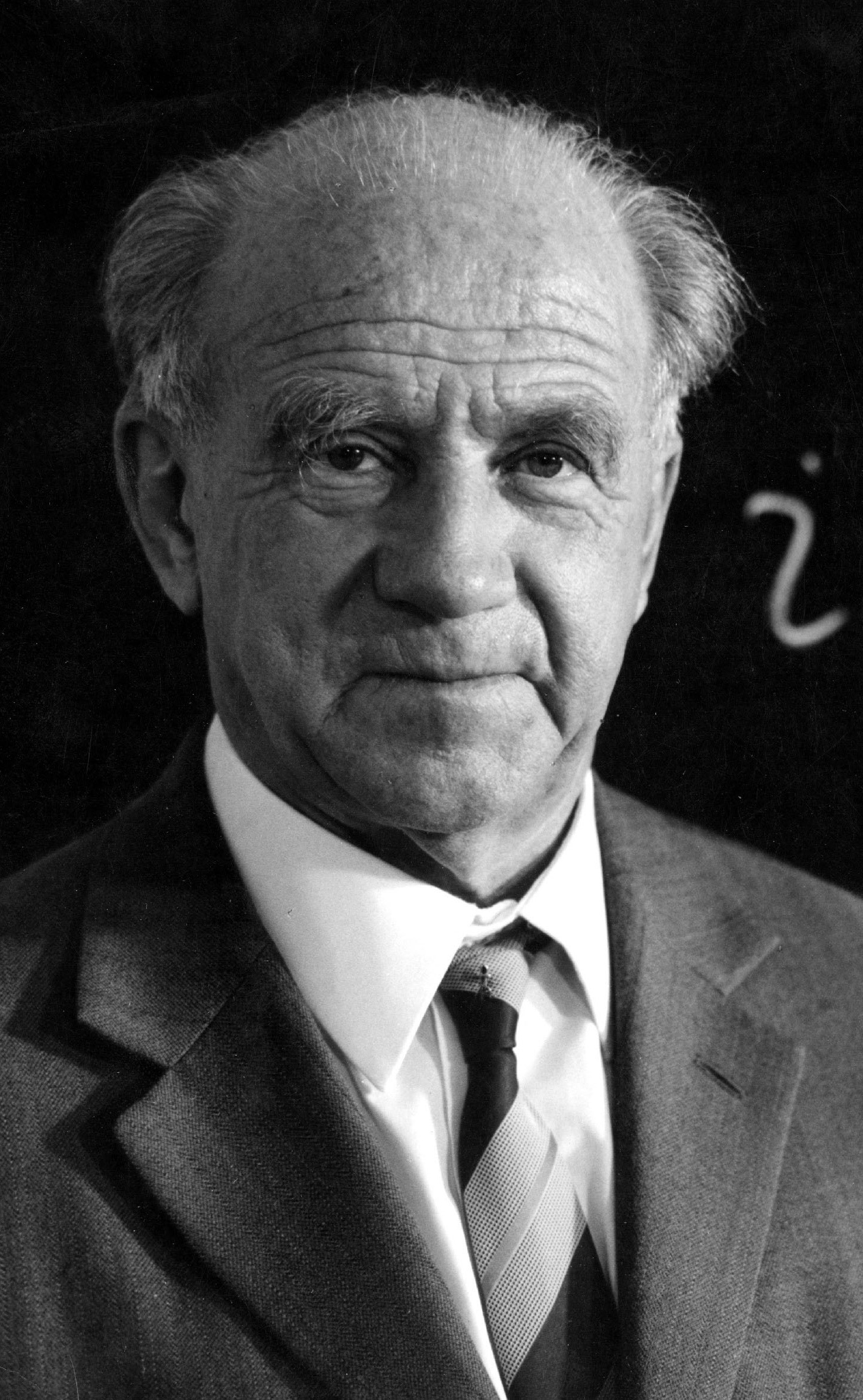

This is a massive book, as large in scale as the author himself, running to over 700 pages, and – at a rough estimate – to something like 300,000 words of text, lightened only by a few photographs, all of them of Gough Whitlam with friends and enemies.

It is not a book for anybody who expects revelations, or even for more light to be shed on the events of 11 November 1975 when a single decision by the governor-general split the nation in a way it has seldom been split politically before. The full story of that day has probably yet to be told, despite all the millions of words and hours of air time which have already been devoted to it.

The Whitlam government is also, in some ways, a curiously impersonal book. What is one to think of an account of the Loans Affair which does not even mention the name of Tirath Khemlani, or of a resume of the political rise and fall of Dr Jim Cairns, which omits any reference to Junie Morosi? Whitlam allows himself only a sidelong look at the ‘conversion’ of Cairns to the values of the alternative society when he says ‘... by now espousing “the economics of love”. He [Cairns] was hardly able to speak a common language with the hardnosed men in his Department [Treasury] whose concern with human values was such that they were quite willing to use unemployment as a tool against inflation.’

On the other hand, Whitlam avoids personalities mainly where they lead him on to dangerous ground. Where he can, with safety, exercise the famous Whitlam wit, and the equally famous Whitlam malice, he does so with great style and verve, hiding his bons mots, like plums, in the dense body of the text, as treats for the persevering reader.

The book is largely what its title suggests, a detailed account of the Whitlam government (‘my government’, as the author invariably says) during its three tempestuous years in power. The theme is justification: Whitlam sets out to demonstrate – and does so very effectively – that whatever its weaknesses, and whatever criticisms have since been levelled against it, the first Labor government for twenty-three years left behind it a legacy of reform in both the domestic and the foreign fields for which it can never be forgotten.

A sub-theme, not unexpectedly is the betrayal of a great leader by fools and knaves. though to be fair this is hinted at rather than laboured. Whitlam seems to see the main villains as the conservative Establishment, the Canberra bureaucrats (especially the ‘hardnosed’ men of Treasury) and the media. A quote from Machiavelli at the beginning summarises the text from which Gough is preaching:

And one has to reflect that there is nothing more difficult to handle nor more doubtful of success nor more dangerous to conduct than to make oneself the leader in introducing a new order of things. For the man who introduces –·it has for enemies all those who do well out of the old order and has lukewarm supporters in all those who will do well out of the new order.

There are some small surprises in the book’s format. It is not, as might have been expected, a chronological account of the years 1972 to 1975, but instead Whitlam has chosen to examine his government’s achievements almost portfolio by portfolio. There are chapters on foreign affairs, the economy, national resources, industrial relations, education, health, social security, transport, housing, Aborigines, migrants, women, the environment, arts, the media, and law reform.

By far the longest section is on foreign affairs, the area in which Whitlam was most at home, and in which he can list with pride his government’s recognition of China, and the granting of independence to Papua New Guinea. ‘If history were to obliterate the whole of my public career save my contribution to the independence of a democratic PNG, I should rest content,’ he writes.

Whitlam takes a few hard swipes at the Hawke government for putting pragmatism ahead of idealism and for shying away from radical reforms. One senses that he may not care much personally for Bob Hawke, as he tells, apropos of nothing at all, a malicious story of Bob and Hazel disporting themselves on the carpet in the best bedroom of The Lodge, then coming downstairs to complain about the fleas.

Apart from Sir John Kerr, for whom his detestation has never weakened, the main villain for Whitlam, as far as Labor history is concerned, is Arthur Calwell, whose conservatism, racism, and sheer bloody mindedness he mercilessly exposes.

The Whitlam Government clearly reflects the paradox of Gough: a reforming idealist with a high view of the human condition, who is at the same time a bad hater with an almost feline maliciousness, and who has a view of his own greatness that sometimes comes close to monomania. We have not seen his like in politics since.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.