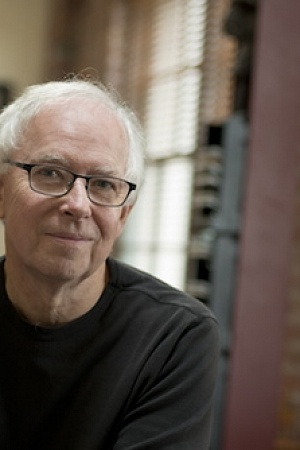

An interview with Ken Ruthven

A new series called Interpretations, published by Melbourne University Press, aims to provide up-to-date introductions to recent theories and critical practices in the humanities and social sciences. Series Editor, Ken Ruthven, answers some questions about the role and reception of critical writing.

Does the brief introduction to the series, which says it is ‘clearly written and up-to-date’, respond to the constant criticism that critical theory uses élite language?

As books by Christopher Norris and Jonathan Culler indicate, even the most complicated types of critical theory can be written about clearly, providing those who undertake such tasks include among their expository skills a mastery of English syntax. Sentences that require to be read twice before they can be understood will be edited out of the Interpretations series. Each book will explain the meanings of appropriate technical terms as they come up, and then use them wherever necessary without further ado. This procedure will depend, of course, on cooperation between writers capable of explaining what they’re on about and readers willing to grant the humanities what has never been denied the sciences, namely, the right to introduce new technical terms in order to articulate new types of knowledge. I believe it’s time to put an end to those recurrent standoffs staged by the Australian media between philistine journos out of their depth in the newer critical discourses and arrogant critical theorists who (to adapt a phrase of Sir Peter Medawar) behave like voluptuaries of the higher forms of incomprehension. What any reader of an Interpretations book will learn is how to use a particular set of critical terms in order to engage with otherwise elusive or obscure issues.

Each book in the series will focus on some aspect of those new developments in the humanities and social sciences which have come into existence by the application of critical theory to traditional preoccupations in these fields. As you know, there was no ‘critical theory’ in the current sense before the late 1960s. And although a few Australian intellectuals were engaging with this largely French phenomenon in the 1970s, it was not until the 1980s that tertiary institutions here started to offer courses on critical theory, and their campus bookshops began to stock the very first guidebooks to it written in English. The series will be up-to-date to the degree that critical theory itself is a recent phenomenon continuously in the bibliographies for the benefit of readers who want to go into matters more thoroughly.

MUP announced the change of general editor, following Stephen Knight’s departure for the UK, by suggesting that ‘Sailing the seas depends upon the helmsman’. How do you see your role?

The nautical metaphor wouldn’t be my favourite choice, although I suppose the general editor might be imagined as steering the series through discursive seas made treacherous in the 1990s by ideological conflicts. Personally, I prefer to think of the series as a space in which some of the newer developments in the humanities and social sciences can be discussed and analysed by people who know about them for the benefit of those of us who do not. In that case, the task of a general editor is to ensure that the available space is filled over the years by as many varieties of the new as possible.

Are these titles in the series literary, social or cultural theory?

To put the question this way is to assume that knowledge can be compartmentalised in ways made familiar by a traditional fragmentation of the humanities into those discrete disciplines which are institutionalised in university departments with names such as History or Philosophy or English. Had there not been problems with such disciplinary arrangements, interdisciplinarity would never have flourished. Such moves were accelerated when scholars located in different disciplinary departments began to study the same critical theorists and to collaborate in the production of certain types of knowledge that don’t ‘belong’ in any of those traditional departments. The Interpretations series will try to accommodate well-informed studies of such highly theorised practices, irrespective of how they might be categorised, on the assumption that they will be of varying interest to people from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds.

What kinds of topics will be covered?

No restrictions are envisaged, provided topics are of contemporary interest and written about in ways that make clear both the theoretical grounds that constitute them, and the critical methods employed in exploring them.

What’s the relevance of the series, and to whom?

The series will not interest people who believe that the world went mad in 1968 and that we should do everything in our power to bring back the 1950s. People who are more curious than appalled by recent developments in the humanities and social sciences, however, might be expected to welcome a series of books that, without patronising their readers, explain and critique some current critical practices in a well-informed and non-threatening manner. By no means all such readers will be enrolled in tertiary courses of study.

Many books of theory produced in Australia are aimed at a very limited audience and are produced on very small budgets. Is there enough of a readership to make a series such as this viable?

Given the relatively small size of Australia’s population, the local market for such books is always going to be correspondingly small, which is one of the reasons why Melbourne University Press is seeking to have the series published by an American university press and by a British press. Nevertheless, two factors are worth bearing in mind. First, and with respect to the potential academic market, it should be noted that the arts faculties of tertiary institutions continue to experience no difficulty whatsoever in attracting students, in spite of the economic hardships they endure and the government’s attempt to lure them into science; and furthermore, that by far the most popular courses in arts faculties are those that engage with the newer forms of humanities and social sciences.

Second, there is an Australian intelligentsia outside the academies that frequents bookshops such as Readings in Melbourne or Gleebooks in Sydney and buys books on critical theory in such numbers as to make it commercially viable to stock them. Much of this material is imported from the USA and the UK. Some of it, however, is produced locally, and I hope that Interpretations will be perceived as an important contribution to that endeavour.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.