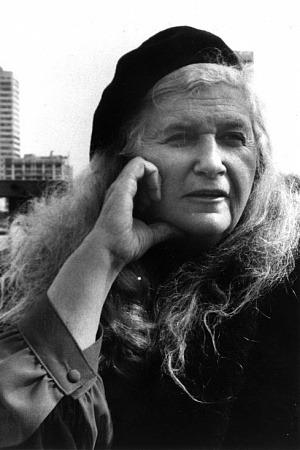

Faith: Faith Bandler, gentle activist

Allen & Unwin, $39.95 hb, 238 pp, 1 86508 841 2

Faith: Faith Bandler, gentle activist by Marilyn Lake

I came to this book after reading Don Watson’s biography of Paul Keating. On the cover of Recollections of a Bleeding Heart, Keating is seen through a window frame, head bent, reading engrossedly, shirt sleeves rolled up – a remote and distant figure. He is seemingly careless of the attention of his photographer, and biographer; a recalcitrant subject.

The contrast with Faith could hardly be starker. On the cover of Marilyn Lake’s biography, Faith Bandler looms large, hands clasped, face alight with laughter and pleasure, in turquoise tones. There is nothing remote about this figure. Faith Bandler wanted an account of her life, and chose Lake as her biographer. This is, Lake tells us, a joint project, the product of frequent discussions between biographer and subject. But why has Lake, Australia’s foremost feminist historian, turned to biography? From the co-authored Creating a Nation (1994) to Getting Equal: The history of Australian feminism (1999), Lake’s work has been directed towards writing women into Australian history. Her signature, as an historian, is a concern with the interaction of masculinity and femininity as a dynamic force in history, and with the way Australian citizenship has always been contested along lines of gender, race and ethnicity. From this, it is apparent why Bandler’s role as an activist and campaigner for indigenous rights interests Lake.

This shift to biography is in some ways brave, for Bandler, like Keating, is a difficult biographical subject. It is not just that she is an unlikely public figure: a politically effective woman in a public culture dominated by men; a political leader outside parliament; a black leader in white Australia; and a highly respected public figure. It is also a difficulty generated by her characterisation as a ‘gentle activist’: a charismatic presence, beguiling and disarming; and a black activist who felt at home in the radical, literary circles of middle-class Sydney. Bandler used the art of gentle persuasion rather than factional alliances and party struggles, and this makes her story very different from those of activists such as Charles Perkins. The title of the book becomes metonymically symbolic of Faith’s character, a celebration of a woman with extraordinary creative and spiritual capacities who campaigned in white gloves and elegant shoes. This is the fabric of the biography, and it remains intact throughout. Who would have thought that Marilyn Lake would characterise a woman as the consummate modern wife, mother and hostess, combining political activism and domestic prowess? Thankfully, Lake offsets this somewhat by including the story of the meticulous arrangements Faith made when she invited the feminist activist Jessie Street to dinner. New yellow curtains were made to match the daffodils on the table; the roast veal dinner was perfect. Street was in fine form, and enjoyed the feast. Nevertheless, she reminded her hostess to conserve her energy for the things that mattered most: her politics and public speaking.

Bandler’s father, Peter Mussing, was one of more than 62,000 men and women brought to Australia from the Pacific Islands in the late nineteenth century to perform manual labour considered unsuitable for whites. In 1902 the newly formed federal government of Australia passed the Pacific Islands Labourers Act, which ordered that all the Islanders brought to Australia to work on the sugar cane plantations be deported by 1906. And so, as a child, Faith learnt from her father about slavery, the ‘blackbirding’ of Melanesians, and their loss of cultural identity as ‘kanakas’. Mussing escaped and walked south, arriving in northern New South Wales around 1903. He settled there and served as a lay preacher in the Tweed River district, marrying Ida Venno, a beautiful woman of Indian–Scottish descent, in 1905. Ida Faith (always called Faith), their sixth child, was born in 1918.

Faith Mussing moved to Sydney in 1940. In the bohemian circles of Kings Cross in the late 1940s, she met a wide range of people on the left and married a Jewish refugee from Vienna, Hans Bandler, in 1952. She was inspired as an activist by Australia’s best-known feminist of the time, Jessie Street, who was by then president of the New South Wales branch of the Australian Peace Council. This story emerges from Lake’s recent work on the history of Australian feminism. By following Bandler’s development as an activist, we can see how the 1950s campaign for Aboriginal rights grew from related campaigns for women’s rights and for peace. This also brings to light the coalition politics of that decade, and the development of Bandler’s commitment to assimilation through the Aboriginal–Australian Fellowship. Later, Bandler and the Fellowship would reject this commitment and advocate integration, signalling support for the retention of a sense of Aboriginal group identity. However, the keynote of coalition politics was the belief that blacks and whites needed to work together in a national conversation directed to constitutional reform and Aboriginal rights.

In the Fellowship and the activism of Street in the late 1950s, Lake locates the genesis of the movement for constitutional amendments that came to fruition in 1967. Charting these developments, Faith brings to light connections and events of historical significance that have largely gone unnoticed. For example, through Bandler’s memories and story, Lake argues strongly for the symbolic significance of the 1967 referendum, contesting recent revisionist readings by Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus. She is also able to chart the institutional trajectory of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI), a major organ for the coalition politics pursued by Bandler and her mentors Jessie Street and Pearl Gibbs. This was instrumental in generating a national political constituency for Aboriginal rights.

Later, after the referendum, ideological shifts changed the grounds of indigenous activism in Australia. The politics of representation undermined the power base of FCAATSI, and discourses of Aboriginality became increasingly important. Non-indigenous blacks such as Bandler were regarded very differently, as culture, not colour, formed the basis of the politics of emancipation. This is the context of her fictions Wacvie (1977) and Welou My Brother (1984), a turning towards the specific network of relationships and obligations between Bandler and her father’s people, the South Sea Islanders, and the campaign to establish the presence of three black minorities in Australia. At the beginning of Faith, Lake suggests that this biography challenges some understandings of Australian history. It does this by returning to preoccupations of her work as a feminist historian: the attention to the lives of those who are not placed in political and institutional hierarchies. Furthermore, Bandler’s ‘gentle activism’ is an example of forms of resistance that embrace the values of domesticity and the private sphere, and these are always important in Lake’s ideas about history. In this, perhaps, she differs from Jessie Street. Most importantly, this biography challenges some of the coordinates that dominate our thinking about race relations. Bandler’s ‘third minority’ is rarely included in our ideas about social justice.

By tracing the changing discourses of Aboriginality, Lake suggests why this is so. In conclusion, Lake advances continuities between Bandler’s lifelong commitment to coalition politics, non-racialism and contemporary campaigns for reconciliation. This is surely the ground of ongoing discussions between biographer and subject, and it embeds reconciliation in a tradition that goes back to the peace campaigns and coalitions of the 1950s and 1960s. As Lake reminds us, it is consoling, in 2002, to be reminded that Australians can lay claim to long-standing traditions of inclusion, acceptance and social justice.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.