La Trobe University Essay | 'On September 11' by Morag Fraser

Primo Levi, in two interviews given almost twenty years ago*, set a standard of critical sympathy that is not only exemplary, but peculiarly apt to the fraught debate about the post-September 11 world and the USA’s place and reputation within it.

Levi was talking about Israel. The interviews were published in the aftermath of the Phalangist attacks on Sabra and Shatila. The horror of the killings in those Palestinian camps was the spur for Levi’s (rare) remarks on Israel, but not their full substance, not the heart of them. Levi, more than most human beings, had seen too much horror to be jolted into revisions of his considered judgment by yet one more instance of it. That does not mean that he was, as a man and as a Jew, unmoved; the depth of his reaction registers in that habitually precise, plain speech of his as clearly as in anyone else’s anguished scream. But it was the state of Israel that was his central concern. And his terse opinion of the then Israeli Defence Minister, Ariel Sharon, was not reactive, not merely a response to Sharon’s role in allowing the Phalangist militia into the camps (his judgment on Yasser Arafat was correspondingly incisive). Levi’s views had been long pondered, and were broadly, not just specifically, critical of Israeli policy. What is remarkable about them is the way in which, in giving them expression, Levi manages to do two things at once. He can utter the most stringent criticism of particular Israeli politicians and régimes while at the same time demonstrating his unwavering commitment and loyalty to Israel. ‘Affectionate and polemical rapport’ he calls it, a sympathy that ‘runs very deep’. That sympathy – a bond, as he says, almost ruefully – is so strong as to be involuntary. And absolutely convincing.

Critical, unblinkered sympathy, or ‘polemical rapport’, shouldn’t be remarkable. But we know it is, and all the more so during war – ‘truth the first casualty’ etc. Certainly, in the post-September 11 world, and throughout the ‘war on terrorism’, with its undefined limits, critical rapport has been straining to find a public, let alone a popular or political, forum. George W. Bush’s dictum – ‘Either you are with us, or you’re with the terrorists’ – hasn’t left much room for critical loyalty. In Australia, a related and engineered polarisation of opinion has slapped a muzzle on debate. For instance Foreign Minister Alexander Downer’s recent, and indecent, haste in consigning Simon Crean to Saddam Hussein’s camp the moment the Labor leader made his decidedly pragmatic criticism (but what about the wheat?) of Australia’s eagerness to line up with the USA in any pre-emptive strike against Iraq.

Post-September 11, in Australia, as in the USA, the ad hominem tactic has had a thorough workout, and the patriotism card is the most thumbed in the deck. As a consequence, it becomes increasingly difficult, even in our two democracies, to debate crucial matters – ones that have potential life or death decisions written into them – and even harder to make the debate count. Spin rules. Public servants are formed into ‘task forces’ to keep its wheels turning. Propaganda thrives. Misinformation becomes a ministerial tool, and denigration replaces argument. Draconian laws that once would have been rejected by a public outraged at the infringement of their civil and political rights are passed into law in an atmosphere of contrived panic. There are plenty of journalists and commentators who have now had a rapid education in the consequences of dissent: abuse, threats, dismissal. And this in vaunted democracies. What kind of example, or hope, one has to ask, does this provide to people in other parts of the globe who live without even the presumption of democracy and freedom? What is lost, in this overheated atmosphere, is understanding, a readiness to reflect, and the analytical capacity to link cause, particularly historically complex cause, with effect. And so we blunder on in a politics of confusion, confabulation and vested interest.

In July this year I spent a lot of time talking to Americans about America. We happened to be in California, but they came from all over – New York, Ohio, Boston, Colorado. It was unsurprising, and characteristic, that the prompt to talk politics came from me. Never underestimate the genuine politeness of Americans, or the ritual formalities of their hospitality. But, once the rude and divisive subject was broached, there was no stopping them.

Their conversations were different from ones I’d had with other Americans last year, in the weeks after the attacks on the Twin Towers and Pentagon. Understandably so. At that time, shock and terrible personal loss, compounded by fear, made speculation about causes of the attacks too painful, too difficult. Criticism, even analysis, sounded like betrayal.

Ten months on, however, this group was vocal. They’d had time to distil their reactions, sift the mass of information and counter-information. Other events had impinged and expanded the context of their considerations. They had watched, night after night, as their television sets brought news of the serial defaulting of US corporate giants such as Enron and WorldCom, and the complicit derelictions of the supposed scrutineers (Arthur Andersen et al.). They had watched, in October 2001, as their Senate voted to approve, without debate, the expenditure of US$60 billion on the as yet unproved missile-defence system. They saw their own and foreign nationals caged in Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay in circumstances that could only be described as legal limbo (and a bizarre parody of civil rights abuse Fidel Castro style). They saw their president sign the USA PATRIOT Act, and they understood its ramifications – surveillance, wiretaps, a legalised invasion of the privacy of financial and medical records – all in the name of national security. They saw the freedoms enshrined in their Constitution eroded and their liberties and civil rights treated with cavalier disregard. And they were obliged to consider the liberties and civil rights of foreign nationals who, after another presidential signing, could be remanded to a military tribunal simply on suspicion of having been associated with a terrorist organisation or linked with subversive individuals or ideas.

They saw the stock market buck and plunge. They watched as some of the highest officers in the land, Vice President Dick Cheney among them, were involved in serious questioning of their financial dealings. They also heard, in every press statement, presidential utterance, in speech after speech, and on the nightly television news, a loop of rhetoric that was mind-numbing in its repetitive banality – a signal for patriotic suspension of the critical faculty. ‘We go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in the world.’ Don’t ask how. Wrong question. They heard, repeated ad nauseam, the same disingenuous evasion – ‘régime change’ – used to presage war. And, if they did not already know, they learned from their own experienced and wary US military veterans (such as Stormin’ Norman Schwarzkopf of Gulf War fame) that the projected régime change could mean a war against another state that, like any number of states including Saudi Arabia, harbours terrorists but that also boasts 400,000 troops, many of them well-equipped and battle-hardened, particularly on the ground. ‘war on terror’, or war on Iraq? They understood that the two are different and that the latter could lead their country into drawn-out strife, and entail American casualties and international isolation precisely at a time when its previous isolationism had ended. It ended in the worst possible way on September 11, but it ended nonetheless.

None of these people wants to live anywhere but in the USA. They are disturbed by the unilateralism of the Bush camp, but they are not about to start a revolution. They want, instead, to see a reassertion of the values and liberties that they, as Americans, cherish. They certainly want to see that at home, and they demonstrated a fair notion of how close is the connection between a revival of liberty and democracy at home and the promotion of liberty and democracy abroad.

Another odd thing: they didn’t resent my asking questions, or voicing criticism. ‘Please write about this,’ they said. They didn’t think of themselves willingly as part of an imperial power, but they were ready enough – their initiative, not mine – to look at the history of US involvement in South America, the Philippines, Vietnam, Cambodia, Korea, the Middle East. They were also ready to look at their ally and former imperial power, Great Britain, and its history of political and economic involvement in the Arab regions that so preoccupy us all, post-September 11. And some of us (not all: this was America) were boning up, as fast as possible, on whatever was being written about Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, oil, weapons trade, Islam and Christianity – fundamentalist or not.

In Australia, my interrogatory bent, or indeed that of any commentator who doesn’t salute and fall in with the Bush line, risks being traduced as agonised, leftist and anti-American. (See, for example, Salusinszky and Melluish’s Blaming Ourselves: September 11 and the Agony of the Left, Duffy & Snellgrove, 2002.) My American conversationalists didn’t see it like that. Together we were neither agonised nor self-flagellating. Concerned? Yes. Critical? Certainly. Un-American? What I heard from them was in the finest tradition of American reflection on the state of their nation, the kind of summation that you’d hope for in an ideal State of the Union address. They weren’t a statistically significant sample of US opinion (though their views are repeated and amplified now in much of the press). They were just a bunch of regular, educated Americans, willing to talk. They were too busy, all of them, to be political activists, and any left–right taxonomy would not have made much sense; their views and allegiances – Democrat, Republican, uncommitted – ranged too widely. What they did have in common, and with me, was a conviction that, in the post-September 11 world, it has become increasingly difficult to voice opposition to the status quo and to have the integrity of that opposition accepted, let alone acted upon. More broadly, it seemed clear to us that, in the world in which the USA has become the dominant power, there is no elbow room for countervailing critique. Oppositions are no longer allowed to be loyal oppositions. That model of civilised, substantive argument in a common cause, for a common good (Levi’s ‘polemical rapport’), disregarded or downright condemned in practice.

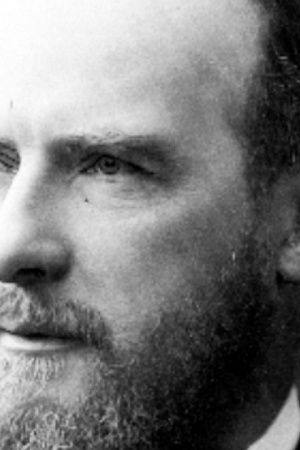

In that sense, there has been a change, or at least an acceleration towards intolerance and an erosion of the liberal ethos that we all treasure. Still, you can’t say we hadn’t been warned. Forty years ago, another old soldier (and Republican president) had something to say about powerful influences on the nature of American democracy:

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence – economic, political, even spiritual – is felt in every city, every Statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognise the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military–industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Dwight D. Eisenhower (17 January 1961)

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s concluding emphasis, on the symbiotic prospering of security and liberty, is what makes his January 1961 presidential farewell so resonant today. Since September 11, security and liberty in America, and to a lesser extent in Australia, have been in an accelerated process of uncoupling. And our leaders have done much to ensure that the citizenry do not become the alert and knowledgeable guardians that Eisenhower nominated as indispensable for maintaining the balance of power in a democracy. Ignorance is now cultivated. In our politicians it is faux ignorance (only a happy few rejoice in the genuine article). ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I didn’t know’ is not a becoming political modesty; it’s the stock legalist formula for evading political and moral responsibility. See the records of the Australian Senate inquiry into the children overboard incident for evidence of the technique, polished and honed. The ignorance in the citizenry is, however, harder to manage. The pesky desire to know, and a few venerable conventions keep getting in the way. Remember the English political apparatchik who tried to bury some bad news about British transport by suggesting it be released on the afternoon of September 11? She came unstuck. We can be sure that many other similar attempts have been successful. The point of political information management is to ensure that we don’t hear the bad news, or, if we do, that we don’t notice too much. There is now a battery of sanctioned techniques (commercial-in-confidence requirements for example) to keep us from knowing. And, if all else fails, invoke national security.

So has the world changed since September 11? No. In large part it is as it was, lopsidedly wealthy, indefensibly poor, and caught up in cycles of poverty, war and ideological strife that keep children out of school, or thrust them in fundamentalist training houses for more war. People still die in their millions from treatable diseases like malaria. War is a potent distraction from the difficult business of breaking cycles of oppression, hunger, disease and misery. And not much education goes on while war is alienating the best energies of nations and peoples.

There have been régime changes. Afghanistan has a new set of rulers, and the Taliban have been scattered. About Al Qaeda we know about as much and as little as we ever did. But we have become much more nervous. India and Pakistan have slightly different grounds for warlike (and nuclear) posturing than before. While the USA has winked, the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians has exploded.

The USA has not so much changed as been shaken into a new period of self-scrutiny, and perhaps a greater awareness of context, of connectedness. Meanwhile, reactive or opportunistic US unilateralism runs ahead of national self-knowledge. That may change, too. But there is no guarantee, even with the current emergence of American pragmatists and wise-heads cautioning against a war with Iraq that has no escape clause and few allies.

September 11 has been the catalyst, or the excuse, for policy initiatives that are extensions of what was happening before. Certainly, in Australia, what we have seen since September 11 is a strengthening of impulses that were already running in our political culture. It is easy to conflate the Tampa incident with the cataclysm of September 11 (as Peter Reith so artfully did), but the MV Tampa was heading into Australian territorial waters some weeks before the USA was attacked. Relations with our Muslim neighbours, Indonesia in particular, were strained well before we had such shocking warrant to link militant Islam and terrorism.

The logic of imperialism does not often lead to enlightenment, let alone universal prosperity. But the USA is a very unusual empire. In its own examination of the nature of its democracy and connection with the rest of the world may lie the fitting memorial to those who died in the furnace of September 11.

*‘Io, Primo Levi, chiedo le dimissioni di Begin’, ‘Primo Levi: Begin should go’, interview with Giampaolo Pansa, La Repubblica, 24 September 1982, and ‘Se questo è uno Stato’, ‘If This Is a State’, interview with Gad Lerner, L’Espresso, 30 September 1984, republished in The Voice of Memory, Primo Levi, Interviews, 1961–1987, edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon, translated by Robert Gordon, The New Press, New York, 2001.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.