Our Members Be Unlimited

Scribe, $39.99 pb, 256 pp

Solidarity forever

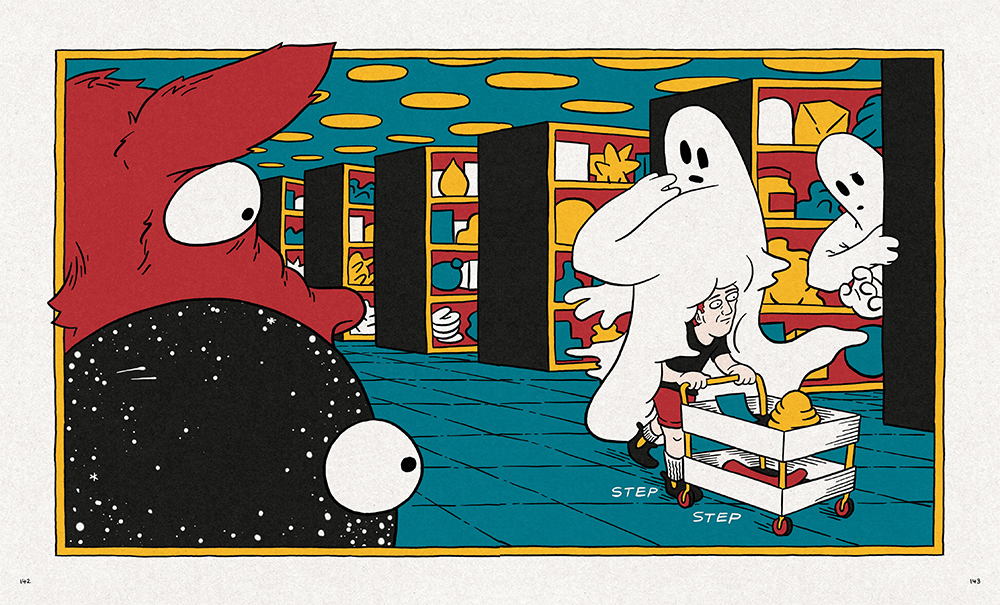

Sam Wallman’s graphic novel Our Members Be Unlimited – ‘a comic about workers & their unions’ – recalls the past victories and the present importance of unions but is haunted by an increasingly attenuated spirit of collectivism. These ‘good ghosts’ of unionism appear halfway through the book during a conversation between two friends, both union members but engaged at different levels of activism. The sequence ends as they watch a fellow worker, oblivious, push his trolley through the trailing ectoplasm of one of these ghosts of collectivism. The two friends look on, bug-eyed, willing him to turn around and notice. So do the ghosts.

This book is a graphic retelling of the history and triumphs of unionism (eight-hour days, weekends, the battle against child labour), and also a polemic: that in the age of Amazon and Uber and Deliveroo, collective bargaining for pay rates and worker rights is more important than ever. As global capital becomes more globalised (and pays less tax), Wallman asserts that workers banding together and demanding better conditions through strike power is a matter of social justice because it will make working people’s lives better. The other characters haunting the margins of this book are sweaty, nervous-looking middle managers and the occasional smugly besuited boss.

It is also an autobiographical account of Wallman’s year as a picker in an Amazon warehouse in Melbourne. Some of the most absorbing sequences in the book detail the minutiae of his Amazon worklife. Wallman’s artistic style (located on the cartooning spectrum halfway between the Simpsons and Salvador Dalí) is well suited to the depiction of subjective experience. His line is bold and clear, but his willingness to delve into the dense physicality of his characters means that his comics are always fleshily embodied. For a book focused on physical labour – pushing trolleys, caring for patients, drawing comics – this is a great advantage. Wallman’s style means that we feel the work that his workers do, and we feel what is done to them. His line insists on the sweat and the strain and the push and the pull. The fatigue. The weariness. It’s skin and it’s bones and it’s arms and it’s legs. We sense the sweet relief of a meal break, or a beer on the footpath outside the John Curtin Hotel.

A spread from Sam Wallman’s Our Members Be Unlimited (Scribe)

A spread from Sam Wallman’s Our Members Be Unlimited (Scribe)

Wallman takes advantage of the visuality of comics texts by rendering mental states as physical phenomena. He shows his own body extruding extra brains and morphing into the trolley which he pushes along the endless Amazon aisles. Wallman’s approach to cartooning combines physical bodies dancing with embodied metaphors across carefully designed pages: reading his work is like watching an editorial cartoon being animated. It’s freewheeling and furious – political and personal.

A double page spread depicts Walt Disney’s metamorphosis from childhood, as the happy son of a socialist drawing pictures of top-hatted fat cats, into an efficiency-obsessed slave driver, railing against his workers’ ‘communistic’ unionising. The pencil-moustached Disney is depicted febrile with rage, as the world around him transforms into a parody of his animated films: lamps with eyes, lightning bolts from tiny brow-circling storm clouds, white gloves …

If this book has a fault, it is that it can occasionally come across as breathless: there is so much Wallman has to say about unionism as a vital brake to unchecked capitalism; so much he has to say about the need to convey this message. Visually it is busy, excitingly so: colour and image bleed to the edge of many of its pages, and Wallman favours visually complex layouts, which give our darting eyes continual puzzles to untangle and decipher. With these levels of visual activity, Wallman or his editors have made a deft choice in making the opening and closing sequences of the book wordless, gently inviting us into and ushering us out of the dense world of this book.

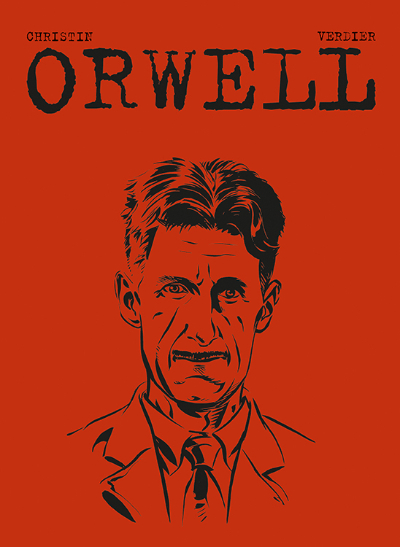

Orwell, by Pierre Christin (script) and Sébastian Verdier (art), is a graphic biography of George Orwell originally published by the major French bandes-dessinées (comics) company Dargaud. Published by English comics outfit Self Made Hero, this translation (by Edward Gauvin) appears on the shelves alongside other Orwell graphic novels, including two adaptations of 1984.

As a writer, Christin is a big name in the French comic industry, and in addition to the beautifully realistic black-and-white artwork by Verdier which tells us the life story of George Orwell, née Eric Arthur Blair, he has called upon other heavy-hitters, including André Juillard, Blutch, and Enki Bilal, who provide short colour artwork interludes which represent Orwell’s major works. This is an elegant solution to the problem of inserting Orwell’s famous oeuvre into his life story.

The brevity of the comics form, as in cinema, imposes a requirement that the script writer needs to take up a tight angle on biographical material, and the names of the chapters: ‘Orwell before Orwell’, ‘Blair invents Orwell’, and ‘Orwellian Orwell’ tell us how Christin and Verdier have approached this task: they focus on the point at which Blair becomes Orwell. They are telling us the author’s life story in order to illuminate his writing. Many of the pages feature Orwell’s writing, denoted by a typewriter font in among the narration and dialogue, another visually elegant solution.

This book is overtly the repayment of an artistic debt that Christin feels to Orwell. But the book is not a hagiography; the ‘heroic’ Orwell is often shown as bull-headed, with unfortunate consequences (getting shot in Spain, contracting pneumonia in England).

For a comic honouring a writer, Orwell features many fine wordless panels to convey Orwell’s feeling for wild England, which was, as per Rebecca Solnit’s Orwell’s Roses, a source of solace and strength for him. This book also deploys wordless panel sequences – the rolling of a cigarette, the shooting of an elephant, a glance at a child’s face in the Underground during the Blitz – each of which imparts an impassive melancholy to the character of George Orwell created in this graphic version of his life.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.