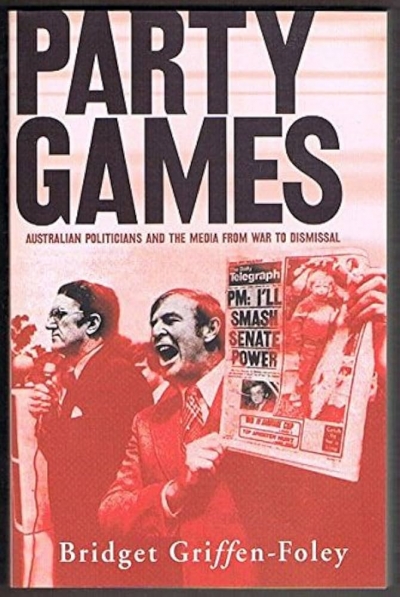

Bridget GriffenFoley

The Men Who Killed the News: The inside story of how media moguls abused their power, manipulated the truth and distorted democracy by Eric Beecher

Changing Stations: The story of Australian commercial radio by Bridget Griffen-Foley

Dennis Altman

In any given year we will read but a tiny handful of potential ‘best books’, so this is no more than a personal selection. Here are two novels that stand out: Stephen Eldred-Grigg’s Shanghai Boy (Vintage) and Hari Kunzru’s Tranmission (Penguin). Both speak of the confusion of identity and emotions caused by rapid displacement across the world. The first is the account of a middle-aged New Zealand teacher who falls disastrously in love while teaching in Shanghai. Transmission takes a naïve young Indian computer programmer to the United States, with remarkable consequences. From a number of political books, let me select two, both from my own publisher, Scribe, which offers, I regret, no kickbacks. One is George Megalogenis’s The Longest Decade; the other, James Carroll’s House of War. Together they provide a depressing but challenging backdrop to understanding the current impasse of the Bush–Howard administrations in Iraq.

... (read more)‘The public are starting to say why don’t they just leave Laws and Jones alone? Why are they highlighting these two?’ said John Laws on 3 August 2000, at the height of ‘cash for comment 1’. He hasn’t been complaining about too much publicity in the current cash for comment controversy. Indeed, Laws has been courting it since 28 April 2004, two days after Media Watch revealed a glowing letter Professor David Flint had written to Alan Jones on Australian Broadcasting Authority letterhead shortly before Flint was to chair an inquiry into Jones’s sponsorship arrangements, and the morning after Flint, during an interview on the 7.30 Report, had acknowledged exchanging several letters with Jones.

... (read more)On-air banter. It’s a staple of radio and television shows seeking to project a friendly, accessible image. Think of the chats between Steve and Tracy on Today, and Mel and Kochie (and, increasingly, their viewers) on Sunrise. Chats between news, sports and weather presenters are routine. It helps if the weather presenter is gorgeous, zany or eccentric, such as Tim Bailey on Channel Ten’s 5 p.m. news in Sydney or the semi-retired Willard Scott on the NBC Today show. (There was never any evident warmth or banter between Channel Nine’s Brian Henderson and Alan Wilkie, one of the few actual meteorologists on air.) The presenters are meant to seem ‘just like us’ as they yarn about their weekends, their birthdays and their children. Some of the chats, particularly between radio hosts, are designed to personalise and promote interest in what’s coming up on the next programme.

... (read more)