Richard Rossiter

Indigo Vol. 3 edited by Sarah French, Richard Rossiter and Deborah Hunn

by Anthony Lynch •

Farewell Cinderella: Creating Arts And Identity in Western Australia edited by Geoffrey Bolton, Richard Rossiter and Jan Ryan

by Wendy Were •

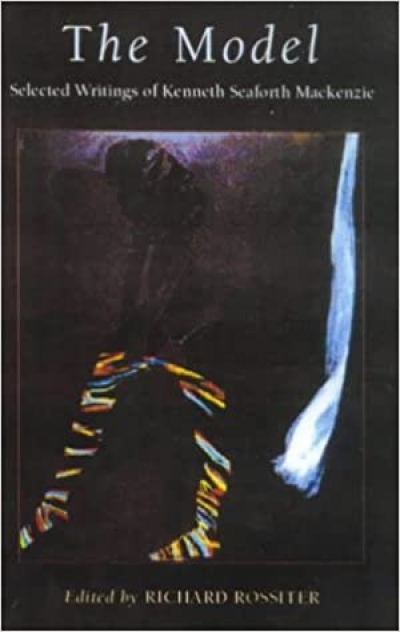

The Model: Selected writings of Kenneth Seaforth Mackenzie edited by Richard Rossiter

by Thomas Shapcott •