Miegunyah Press

Through Artists’ Eyes: Australian Suburbs and their Cities, 1919-1945 by John Slater

by Daniel Thomas •

Treasures edited by Chris McAuliffe and Peter Yule & Treasures of the State Library of Victoria by Bev Roberts

by Christopher Menz •

Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land by Donald Thomson, edited by Nicolas Peterson

by John Mulvaney •

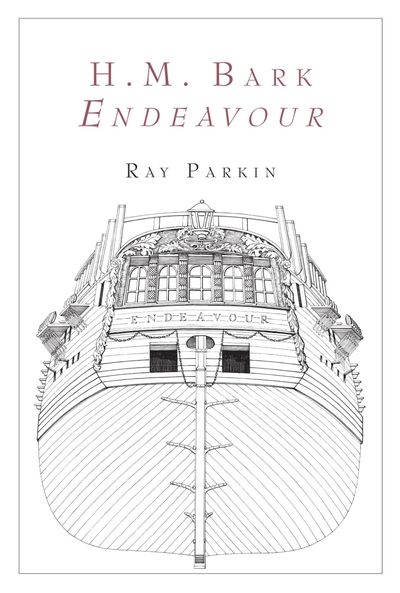

The Global Reach of Empire: Britain’s maritime expansion in the Indian and Pacific oceans, 1764–1815 by Alan Frost

by Donna Merwick •

Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines by David Unaipon, edited and introduced by Stephen Muecke and Adam Shoemaker

by Susan Hosking •

Colonial Consorts: The wives of Victoria’s governors, 1839–1900 by Marguerite Hancock

by Paul de Serville •

The Solitary Watcher: Rick Amor and his art by Gary Catalano

by Bernard Smith •