Death Dance

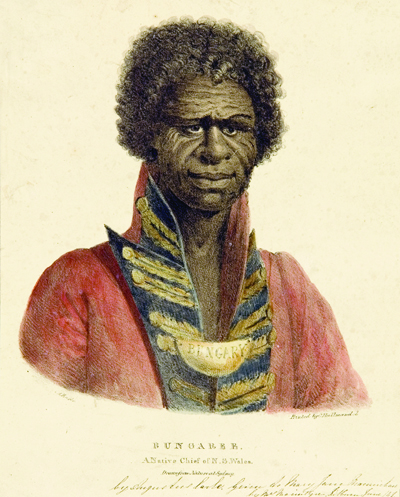

I am at the exhibition ‘National Treasures from Australia’s Great Libraries’. I have come to see a picture of a man named Bungaree. I am standing in front of him, but I am distanced. The painting is glazed, low-lit, hung on a wall on the far side of quite a deep display case. If I stand up straight he is in focus, but too far away for me to see the details. As I incline my torso forward to examine the picture more closely, we exchange bodily gestures of courtesy: I bow and he raises his hat. But in this exchange I lose clarity. The edges blur. I have to reach for my spectacles. I think about Lord McCartney’s diplomatic mission to China in 1792, which almost collapsed before it began through the refusal of the British ambassadors to prostrate themselves before the Emperor Qianlong in the courtly ritual of the kowtow. The cultural distance between London and Beijing was as great as the geographical: 5000 miles of mutual incomprehension.

I refocus, peering as closely as I can reach. This first corner of the exhibition, ‘Under the Southern Cross’, is about European exploration. Over to the left, in the corner of my eye, there is a fine terrestrial globe made in London by Richard Cushee and Thomas Wright in 1731, which shows Australia as New Holland. Above it hangs the National Library’s well-known portrait of Abel Tasman and his family, attributed to Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp. Immediately to Bungaree’s left is the famous Flinders Map, the 1814 ‘General Chart of Terra Australis or Australia’. This is entirely appropriate, a neat curatorial juxtaposition. Selected for his ‘good disposition and manly conduct’, Bungaree acted as the Aboriginal liaison officer on Flinders’ great Investigator voyage of 1802–03, making him the first first Australian to circumnavigate the continent. The trip also made him the first of a long line of indigenous expeditioner–advisers, preceding Oxley’s Toodwit, Major Mitchell’s Yuranigh, Dick, ‘the brave and gallant native guide’ of the Burke and Wills expedition, Jacky Jacky, who completed Edmund Kennedy’s Cape York expedition after Kennedy’s death, Tommy Windich, who accompanied the Forrest brothers across the Gibson Desert, down to Ray Raiwala, Donald Thomson’s guide to Arnhem Land in the 1930s.

The exhibition’s curators and designers have evidently recognised the necessary connection between exploration and empire, between discovery and dispossession. At this point in the show, the two categories segue from one to the other. Bungaree personifies the intersection. He is the link, the hinge, the fulcrum, the wedge. He stands between map and title.

Beneath his portrait, the case against which I press my belly as I lean forward contains the Endeavour journals of Captain Cook and of Sir Joseph Banks. The journals are both open to the day of the British landing at Botany Bay: 19 April 1770. Today is the twenty-first – two days late. I consider playing with time, fudging the truth of my visit so that I can write of the shivering coincidence of an anniversary encounter, but dismiss the idea: I wish to be honest. Besides, the numbers are trivial. The empirical realities I am looking for are more temporally extended. They are the lived human histories of intention, encounter, response. I look down at the Cook journal. It is not in the exhibition label, and I cannot find it in the faded brown ink of the Captain’s surprisingly untidy hand, but I recall the famous line: ‘all they seem’d to want was for us to be gone.’ ‘Warra, warra’, the Aborigines called, shaking their spears and waddies. ‘Go away.’

In the case to the left, there are two other Cook-related documents. The first is the secret ‘Additional Instructions’ from the Admiralty, in which he is authorised to search for and claim the Great South Land in the name of Great Britain. The second is a letter from James Douglas, fourteenth Earl of Morton, and then president of the Royal Society, containing hints on how to deal with native peoples encountered on the voyage. The page on display includes the observation that ‘They may naturally and justly attempt to repell [sic] intruders, whom they may apprehend are come to disturb them in the quiet possession of their country, whether that apprehension be well or ill founded.’ Elsewhere in the letter is a more straightforward assessment, one which is in direct contradiction of the Admiralty’s orders: ‘They are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit … No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or to settle among them without their voluntary consent.’

In the case to the right, ‘natural and … legal’ indigenous ownership is reasserted. The papers in this vitrine document the beginnings of native title in Australia: notes from a speech by Eddie Koiki Mabo delivered at the University of Townsville in 1981; Mabo’s texta-colour map of his customary land holdings on Mer (Murray Island); and his hospital diary, in which he reflects on his life and his struggle for land rights.

I look up again at Bungaree. His lifted hat and benevolent expression are at once courteous and condescending; regal, in fact. They epitomise the casual self-possession of the New South Wales Aborigines described by the colonial poet Barron Field: ‘They will not serve … they bear themselves erect, and they address you with confidence, always with good humour, and often with grace … They have bowing acquaintance with everybody, and scatter their How-d’ye-do’s with an air of friendliness and equality, and with a perfect English accent.’ Bungaree’s erect and stately pose, his gracious and formal gesture of greeting, are those of a proprietor. Captain Faddei Bellingshausen records Bungaree’s welcoming visit to the Russian exploring ship Vostok in 1820, and his confident opening address: ‘Indicating his companions, Bungaree said “These are my people”. Then pointing at the whole northern shore, he said, “This is my shore.”’ My shore? My land, perhaps? But what land, exactly? Here we encounter a slight mistranslation, one of contact history’s inevitable misapprehensions and misreadings. In recent years, following the anthropologist Norman Tindale, it has become common to refer to the Aboriginal people living around Port Jackson at the time of the British annexation as ‘Eora’. This is undoubtedly a positive thing. It gives those who bore the initial brunt of the white invasion an identity more specific, more personal than a general Aboriginality. It thereby conveys a certain dignity, offers a posthumous respect.

It is also not quite right. Although recorded in the earliest written word lists – those of David Collins and John Hunter from the 1790s – Eora seems never to have been a national or tribal name as such. Rather, it appears to derive from the Darug word ‘ora’, meaning place or country, with the ‘e’ as some kind of indicative prefix: this country, my country. The same sort of grammar gives us Kuringgai, the name given to the tribes which lived north of Port Jackson. The root word is the now-familiar ‘kuri’ or ‘koori’, meaning ‘man’, with the suffix denoting possession, thus ‘belonging to the men’, the place of, or pertaining to, those who were there. It is simple and circular, this Aboriginal equation of place and people and language, and until 1788 it was unchallenged.

‘The lines between language, dialect and accent are always fluid, and the more so in non-literate cultures’

Settlers will never get these names exactly right. The lines between language, dialect and accent are always fluid, and the more so in non-literate cultures. Identification of tongue and territory is further complicated by the Aborigines’ regular inter-nation trade, marriage and ceremonials, and the common multilingualism of adjacent tribes. Nevertheless, the consensus ethno-linguistic cartography of maritime southern New South Wales seems to be roughly as follows: from Jervis Bay in the south to Botany Bay lived the Dharawal. Moving up the coast, between Botany Bay and Port Jackson were the Darug speakers (or Eora), while above Port Jackson as far as Tuggerah Lake lived the Kuringgai. Further north still, and extending as far as the Hunter River, was Awabakal country.

Working on the basis of early ethnographic accounts, the 1828 colonial census and records of blanket distribution, James Kohen has identified a dozen distinct clans or bands within the Kuringgai tribe. And it is here that we find Bungaree, a Kuringgai man, probably from the Broken Bay–West Head group known as the Carigal. Again, we cannot be entirely certain. The engraved brass gorget presented to Bungaree by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1815, the first of the colonial ‘king plates’, was inscribed simply ‘Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe’. What we do know for sure is that although Bungaree and his extended family spent their days fishing on the harbour or wandering the streets of Sydney Town, they usually returned every night to the north shore, the Kuringgai side of the harbour.

What is the purpose of these speculations, this apparent diversion? In Beneath Clouds, Ivan Sen’s award-winning blackfella road movie of 2002, the two hitchhiker-runaways, Vaughn and Lena, are given a lift by some of Vaughn’s cousins. An older woman passenger divines Lena’s (hitherto unadmitted) Aboriginality, and asks: ‘Wher’re your people from, girl?’ Place of origin, family of origin: these are the first questions of first peoples, even today.

Art historians are likewise preoccupied with beginnings, with genealogy and location. I am interested in this man Bungaree in part because his image occupies a place – Sydney in the 1820s – not far from the beginnings of Australia’s settler art history. He is represented many times in drawings, watercolours and prints. We have more pictures of Bungaree than of any contemporary individual, black or white: a total of some eighteen portraits (give or take one or two subject to definitions and attributions), as well as half a dozen incidental appearances in broader landscapes or figure groupings. His is among the first full-length portraits in oil to be painted in the colony, and the first to be issued as a lithograph.

Beyond his personal, individual celebrity, Bungaree also stands not too far from the start of a long and ongoing thematic series of works of art: European representations of Aboriginal Australians, a pictorial tradition first explored by Geoffrey Dutton in 1974, and which he simply and succinctly called ‘white on black’. And while Augustus Earle’s portrait of 1826 (reproduced on the front cover this month) is not one of those universally recognised historical paintings such as John Glover’s House and garden, William Strutt’s Black Thursday, or Tom Roberts’s Shearing the rams, nor is it some obscure colonial oddity. A highlight of the Rex Nan Kivell collection at the National Library of Australia, it featured in the Art Gallery of New South Wales’s important 1988 exhibition ‘The Artist and the Patron’. Certainly it has been widely enough known since the 1990s to be reiterated in paintings and prints by Stephen Bush, Juan Davila, Julie Dowling and Clinton Nain, and in Murray Walker’s Federation Tapestry. I am interested in Bungaree because of the distance his image has travelled.

The man himself covered a fair bit of territory during his lifetime. In 1799, when in his late teens or early twenties, he sailed with Matthew Flinders on the Norfolk to Hervey Bay. A couple of years later, he accompanied James Grant on the shorter trip to Newcastle, before serving again with Flinders on the Investigator. Finally, with middle age approaching, he volunteered to go with Philip Parker King to the Gulf of Carpentaria, on a mission to fill in a few of the gaps in the earlier coastal survey.

Bungaree’s conceptual journeys were even longer, and certainly more difficult

Bungaree’s conceptual journeys were even longer, and certainly more difficult. He was born probably some ten to twelve years before the arrival of the British, and presumably enjoyed a traditional childhood, practising for grown-up hunting and war. Although the Kuringgai were initially relatively undisturbed by the growth of the settlement at Sydney Cove, they were devastated by the smallpox epidemic of 1789, and tribal structures of kin, territory and law were significantly loosened. By the late 1790s Bungaree and the surviving Carigal had drifted south to Port Jackson, now home to several thousand British convicts and settlers. Then followed the young man’s various maritime excursions. After 1810 the patronage of Governor Macquarie gave him a farm at George’s Head (not a success), a fishing boat (a rather more useful and profitable gift), various items of cast-off officer’s uniform, a formal title and a quasi-official appointment as the colony’s chief Aboriginal interpreter and master of ceremonies.

Augustus Earle, Bungaree A Native Chief of N.S. Wales, c.1829–38, lithograph, (courtesy of Art Gallery of South Australia)It is in this capacity that Bungaree finds his lasting fame. According to his biographer Keith Vincent Smith, an historical tradition maintains that Bungaree, as ‘host’ of the Sydney Aborigines, always attended Macquarie’s annual Native Conferences at Parramatta, and was responsible for introducing the other tribal chiefs or elders to the governor on these occasions. Much better documented is the position mockingly described by James O’Connell as ‘chief … boarding officer and official welcomer and usher’, his self-appointed role in greeting European ships as they entered the harbour. Of the several accounts of Bungaree’s visits to newly arrived vessels, that of Peter Cunningham in his Two Years in New South Wales (1827) can serve as exemplar. Cunningham describes the experience of an immigrant arriving in Port Jackson:

Augustus Earle, Bungaree A Native Chief of N.S. Wales, c.1829–38, lithograph, (courtesy of Art Gallery of South Australia)It is in this capacity that Bungaree finds his lasting fame. According to his biographer Keith Vincent Smith, an historical tradition maintains that Bungaree, as ‘host’ of the Sydney Aborigines, always attended Macquarie’s annual Native Conferences at Parramatta, and was responsible for introducing the other tribal chiefs or elders to the governor on these occasions. Much better documented is the position mockingly described by James O’Connell as ‘chief … boarding officer and official welcomer and usher’, his self-appointed role in greeting European ships as they entered the harbour. Of the several accounts of Bungaree’s visits to newly arrived vessels, that of Peter Cunningham in his Two Years in New South Wales (1827) can serve as exemplar. Cunningham describes the experience of an immigrant arriving in Port Jackson:

King Boongarre [sic], too, with a boatload of his dingy retainers, may possibly honour you with a visit, bedizened in his varnished cocked hat of ‘formal cut’, his gold-laced blue coat (flanked on the shoulders by a pair of massy epaulettes) buttoned closely up, to evade the extravagance of including a shirt in the catalogue of his wardrobe; and his bare and broad platter feet, of dull cinder hue, spreading out like a pair of sprawling toads, upon the deck before you. First, he makes one solemn measured stride from the gangway; then, turning round to the quarter-deck, lifts up his beaver with the right hand a full foot from his head (with all the grace and ease of a court exquisite) and, carrying it slowly and solemnly forwards to a full arm’s length, lowers it in a gentle and most dignified manner down to the very deck, following up this motion by an inflection of the body almost equally profound.

Advancing slowly in this way, his hat gracefully poised in his hand, and his phiz wreathed with many a fantastic smile, he bids massa welcome to his country. On finding he has fairly grinned himself into your good graces, he formally prepares to take leave, endeavouring at the same time to take likewise what you are probably less willing to part withal, namely, a portion of your cash. Let it not be supposed, however, that his Majesty condescends to thieve: he only solicits the loan of a dump, on pretence of treating his sick gin to a cup of tea, but in reality with a view of treating himself to a porringer of ‘Cooper’s best’, to which his Majesty is most royally devoted.

This is the reputation that sticks. Not Flinders’ assessment. In the published account of the Investigator voyage, Flinders describes Bungaree as ‘good-natured’, ‘modest’ and ‘humble’ in himself, and ‘gallant’, ‘brave’ and ‘worthy’ in his work for the expedition. He also describes him as a friend. Not the view of Lieutenant Menzies, Commandant at Newcastle, who thought him ‘the most intelligent of that race I have yet seen’. Not even the more general opinion expressed in the New South Wales Almanackof 1815: ‘This native has even been distinguished for the docility of his manners; his kind and tractable disposition; his friendly demeanour; his general utility.’

Bungaree is rather remembered as he was in the decade before his death, through anecdotes such as Cunningham’s, and through their reiteration and fanciful embroidery by subsequent writers. He is represented through portraits such as those by Augustus Earle and Charles Rodius, portraits reflecting the pronounced 1820s British taste for paintings and prints of low life and ‘eccentric characters’. Bungaree is not remembered as the explorers’ aide, the first Aborigine to circumnavigate Australia. He is not remembered as the first Aboriginal agriculturalist. He is not remembered for his political power, either as Kuringgai leader or as interpreter and negotiator for British governors. No, he is remembered as a comic metonym of early colonial Sydney: mimic, beggar, drunk.

Economic dependency and substance abuse are the familiar gifts of conquerors to indigenous peoples. But the mimicry is intriguing, the pantomime, the ‘dancing with strangers’, to use Inga Clendinnen’s potent phrase. In Clendinnen’s courageous and imaginative reconstruction of the First Fleet’s first year in New South Wales, the book’s title, cover image and first chapter summon the unlikely image of Britons and Aboriginals hand in hand, stepping out together on the light fantastic toe. She traces the first tentative, fragile contacts between whites and blacks, and the curious forms of that original interaction; not only dancing, but combing hair, whistling, singing, exposing sexual parts, a whole gamut of ‘clowning pantomimes’.

Yet, while for the 1788 European dancing is just one among many possible performances, a lightweight social pastime which signifies only high spirits, preliminary courtship, or a degree of class distinction, for Aboriginals the dance is primary, essential. Before any other form of exchange, whether of words, gifts or blows, strangers and meetings must be defined choreographically. The song and dance of encounter is a place of pause, a neutral space in which identity, location, authority and purpose can safely be established, and the expectations, the rights and the responsibilities of each side articulated. The convention was nicely described by the nineteenth-century Wurundjeri tribal leader and artist William Barak, whose paintings of traditional ceremonial life include many corroboree scenes. Speaking to the naturalist and pioneer anthropologist Alfred Howitt, Barak explained that among the tribes of the Kulin nation, ‘when visitors came to meetings from some distant place they danced and the hosts looked on; for it was for them to dance and make friends with each other, being from a distance’.

The occasional or introductory dance has left plenty of footprints in the dust of colonial art. Corroboree images or dancing figures are the common, continuous currency of white on black. Aboriginal dancers appear in the work of dozens of colonial artists: in the printed accounts of French and British exploring expeditions and of the early history of the colony of New South Wales; in Joseph Lycett’s Awabakal album; in John Glover’s Van Diemen’s Land oil paintings and S.T. Gill’s and George French Angas’s South Australian watercolours; in countless popular prints and amateur sketches.

Reciprocal performances are much less frequently referenced in the colonial archives, but an Aboriginal expectation can nevertheless be clearly inferred. In the relatively innocent encounter between Arthur Philip and the Kuringgai at Broken Bay in 1789 – drawn by Lieutenant Bradley of the Sirius, and reproduced on the cover of Clendinnen’s Dancing with Strangers(2003) – the hand-holding attitudes (a gavotte? an Aboriginal line dance?) imply equality, connection and instruction. Bradley’s capering figures invoke an image from another beach, in another hemisphere, in another century: Zorba the Greek and the young schoolteacher doing the syrtaki. In Tasmania a few years later, Antoine Piron, draughtsman on the Bruny d’Entrecasteaux expedition, blacked up with charcoal and danced with the Palawa at Rocky Bay. In 1818 Piron’s compatriot and fellow artist Jacques Arago impressed Shark Bay Aborigines by rattling a pair of castanets.

From HMS Beagle’s voyage to Australia in the late 1830s, we have a fine example of both the serendipity and the seriousness of cross-cultural etiquette. While at Adam Bay, on the Western Australian coast, two of the expedition’s survey staff put ashore to undertake a routine calibration of the ship’s compasses. Halfway through their observations, there suddenly appeared on the low cliffs behind the beach a large group of Aborigines, foot-stampingly, beard-chewingly and spear-quiveringly angry at the white men’s intrusion. The Beagle’s commander, John Lort Stokes, continues the story: ‘It was, therefore, not a little surprising to behold this paroxysm of rage evaporate before the happy presence of mind displayed by Mr Fitzmaurice, in immediately beginning to dance and shout, though in momentary expectation of being pierced by a dozen spears. In this he was imitated by Mr Keys, who … joined his companion in amusing the natives; and they succeeded in diverting them from their evident evil designs, until a boat landing in a bay near drew off their attention.’ While hopelessly gauche, even to a degree incomprehensible in Aboriginal terms, the Englishmen’s dance was nevertheless the proper form for visitors, and earned Fitzmaurice and Keys at least partial access to Aboriginal social space, and a reprieve from violence.

A more conscious and equal Terpsichorean trade had occurred earlier at Bribie Island-Moreton Bay, on Flinders’ Norfolk voyage, when our man Bungaree was part of the crew. Perhaps Bungaree was even responsible for arranging protocol on this occasion. Certainly he was confident in his role as go-between; it is reported that, when the Aborigines – probably Undanbi people – appeared, he ‘went up to them in his usual undaunted manner’. After a preliminary exchange of gifts – caps, port and ship’s biscuit for the natives, headbands and hair string armbands for the whites – the local people presented a dance and a song. In reply – and, I would venture to suggest, probably at Bungaree’s urging – three of the Norfolk’s sailors attempted a Scottish reel, though Flinders noted with regret that ‘for want of music they made a very bad performance’. Nevertheless, the ritual was repeated a week later when the Norfolk’s crew again visited the Undanbi, and were again greeted with singing and with a slow dance in which ‘their hands being held up in a supplicating posture … the tone and manner of their song and gestures seemed to bespeak the good will and forbearance of their auditors’. On this occasion, it was Bungaree himself who responded in kind, to complete the obligations of indigenous courtesy. Much preferring the music of the Undanbi to that of the Darug, and missing the point rather, Flinders was again disappointed by his team’s performance, observing that ‘the song of Bongree [sic] which he gave them at the conclusion of theirs, sounded barbarous and grating to the ear; for [he] was an indifferent songster, even amongst his own countrymen’.

‘What I think these anecdotes show is not only the centrality of corroboree, of dance and song in Aboriginal culture, not only its specific application within rituals of encounter, but also the mutual obligation it implies, the requirement of reply, participation, reciprocity’

What I think these anecdotes show is not only the centrality of corroboree, of dance and song in Aboriginal culture, not only its specific application within rituals of encounter, but also the mutual obligation it implies, the requirement of reply, participation, reciprocity. There is in the literature one further instance of response that is relevant to Bungaree’s story. Again it is from a Flinders expedition, though in this case from the incoming leg of the Investigator trip, before Bungaree was on board. At their first extended anchorage, at King George’s Sound, in Western Australia, Flinders and his crew had several weeks of tentative but cordial intercourse with the local Nyoongar. Towards the end of their stay, Flinders ordered the small detachment of marines under his command to drill on the parade ground of the beach. Flinders describes both the foreigners’ action and the indigenous reaction:

I ordered the party of marines on shore, to be exercised in their presence. The red coats and white crossed belts were greatly admired, having some resemblance to their own manner of ornamenting themselves; and the drum, but particularly the fife, excited their astonishment, but when they saw these beautiful red-and-white men, with their bright muskets, drawn up in a line, they absolutely screamed with delight; nor were their wild gestures and vociferation to be silenced, but by commencing the exercise, to which they paid the most earnest and silent attention. Several of them moved their hands, involuntarily, according to the motions; and [an] old man placed himself at the end of the rank, with a short staff in his hand, which he shouldered, presented, grounded, as did the marines their muskets, without, I believe, knowing what he did.

The old man knew exactly what he was doing: learning by imitation, drilling his body into remembering the forms of the strangers’ performance. For Aborigines, dance is a somatic mnemonic, the literal embodiment of story. Many early contact memoirs describe how good the natives were at this kind of physical learning, how quick on the uptake. Louisa Ann Meredith, for example, writes in her Notes and Sketches of New South Wales (1844) of one man who ‘learned to waltz very correctly in a few minutes’. And they had not just quick memories, but long ones, too. Through the old man’s remembrance and reiteration, the parade drill of Flinders’s marines eventually became a part of the local culture, a formalised corroboree known as the Koorannup, which was still being performed by Nyoongar over a century later.

I would argue that Bungaree’s clowning welcomes, his much-celebrated imitations of colonial governors, fall within this category of encounter-dance. His mimicry of English manners signifies not submission to the imperial power, but simply the adoption of new gestures to permit the maintenance of Aboriginal protocols of meeting under the new régime.

One particular story bears repeating. In his History of New South Wales (1834), the Reverend John Dunmore Lang recalls a meeting with Bungaree in his boat on the Parramatta River: ‘My brother requested Bungary [sic] to show us how Governor Macquarie made a bow. Bungary happened to be dressed at the time in the old uniform of a military officer, and accordingly standing up in the stern of his boat and taking off his cocked hat with the requisite punctilio, he made a formal bow with all the dignity and grace of an officer of the old school. My brother requested him to show us how Governor Brisbane made a bow, to which Bungary very properly replied in broken English ‘top top; bail [not]me do it that yet; top nudda Gubbana come’. In short, Bungary could exhibit the peculiar manner of every governor he had seen in the colony; but he held it a point of honour never to exhibit the reigning Governor.’

This story seems to be intended purely as comedy, as an illustration of the wide-eyed, innocent black man’s inability to comprehend the complexities of European social manners. Indeed, Bungaree’s response does seem a bit confused, a bit overstated, even a bit peculiar. But if we dispense with Lang’s idea of politesse, and instead cross-reference to the traditional cultures of, say, Central Desert Aborigines, which have been mapped in more detail and with more understanding by twentieth-century anthropologists and sociologists, an explanation emerges. It is possible to think of the ritual performance – the actual manner of bowing – as being a story belonging to the particular governor, with Bungaree – the white man’s black man, vice-regal favourite and master of ceremonies – taking the role of the skin-group uncle, the ritual boss or agent of the story. When Governor Brisbane is present amongst his people, it is his privilege, indeed, his responsibility, to deliver this small dance of identity, power and courtesy, as required by the circumstances of encounter. Bungaree, on the other hand, while he knows the script intimately, can only perform it himself if the actual owner, the originator, is gone away. For whites, the Bungaree’s impressions are little more than parlour-games, charades; for the man himself they are potent summonings of absent authority.

It is not so much story as authority that I am calling on here in this brief salute to Bungaree. What Augustus Earle’s portrait conveys are three important concepts in Aboriginal culture; or rather, one concept and two particular inflections or applications of it. The core idea is the Aboriginal dance of encounter, the indigenous notion that identity and greeting should initially be enacted or represented by bodily motion, that a ritual physical performance is required to neutralise the charged, uncertain and dangerous space of meeting.

Early contact Aborigines are always dancing for, if not always with, the white strangers. The first extension of the idea that such a dance demands a response is that there should in fact be a ‘with’. Dance yourself, your people, your totem, your place, and I will dance you back. When things are managed properly, the Undanbi dancers receive in reply a Scottish reel, albeit a fairly rough and ready one. For his carefully choreographed welcoming ritual, Bungaree receives ships’ captains’ and emigrants’ acknowledgment of his status, albeit in mocking tone. He gets a drink, at least. The second sub-concept, associated with the expectation of reciprocity, is the notion of mimicry. The Nyoongar’s trance-like following of the marines’ movements, or Bungaree’s careful attention to the particular mannerisms of successive governors suggest, when taken in context, that for the Aborigines imitation is, if not the sincerest form of flattery, then at least the customary form of respect.

First imitation, then repetition. This is not a totally unfamiliar concept for Europeans; Judaeo-Christian literary mannerism often entails statement, restatement in other words, and then a third reiteration, a tripartite exploration of metaphor, a trinity of revoicing. Aboriginal song and dance likewise reinforce the meaning of a story or a map or a social role or an encounter by copying it, making it, singing it, telling it over and over and over a long, long time, as long as Aboriginal possession, as long as a piece of hair string.

‘As hopeful visions of a national future shrink to the narrow compass of the next business or electoral cycle, or at most to the superannuated end of each of our individual aspirational lives, it is not surprising that more and more Australians choose to explore, invade and settle in that other country, the past’

As hopeful visions of a national future shrink to the narrow compass of the next business or electoral cycle, or at most to the superannuated end of each of our individual aspirational lives, it is not surprising that more and more Australians choose to explore, invade and settle in that other country, the past. Some seek only the slow, comforting rhythms of generation succeeding generation, and perhaps a convict or two to decorate the family tree. For others, the journey is more purposeful. They are in search of undiscovered or unfamiliar narratives for postmodern microhistories, recyclable imagery for post-colonial paintings, settings and characters for magical-realist novels. Meaner spirits want material for the history wars: lower body counts to distract from the frontier ethnocide, ancestral Aboriginal poverty, drunkenness and violence to explain and excuse failed government policy. Whatever their intentions, whether words, gifts or blows, whoever goes travelling in the Australian colonial past must not only encounter what Bernard Smith called in his 1980 Boyer Lectures ‘the Spectre of Truganini’: they must also face the confident, graceful greeting dance of Bungaree.

I step back from the glass case. Who is this man who salutes me from the wall of the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, in 2006, and from the rough streets of The Rocks, Sydney, in 1826? Is it Bungaree of the Carigal clan of the Kuringgai tribe, from Broken Bay–West Head country? Is it indeed Bungaree, husband of Matora, father of Young Bungaree and Long Dick and Sophie and stepfather of Gaouenren; also husband of Rose and father of John Bungaree; also great-great-great-great-great-grandfather of Warren Whitfeld, presently of Woy Woy? Or is it rather Bungaree, ambassador of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, dressed in Macquarie’s discarded general’s uniform and cocked hat, decorated with Macquarie’s medallion and standing in front of the Sydney Cove fort that bears Macquarie’s name? Or possibly even Bungaree, the proxy for Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane, painted by Augustus Earle, the artist of Brisbane’s official portrait, bowing the Brisbane bow, while behind him in the harbour is HMS Warspite, the Royal Navy frigate commanded by Brisbane’s first cousin? Which is the real Bungaree? Or is he lost completely, the very type of post-colonial theory’s mottled, creolised, unsubstantial, subaltern mimic man?

A school tour comes into the exhibition gallery. For a few minutes, I move still further back and leave exploration to the young. I watch from the shadows of convict punishment. The guide provided by the library is dynamic, intelligent, well-practised, and speaks with a marked Spanish accent. The students, from a Catholic secondary school, are neat, interested, well-behaved; and nine of the class of twenty-one are of East Asian descent. They listen to brief disquisitions on the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English, on the European discovery and naming and settlement of Australia. Bungaree is not included in the programmed tour. No one wants to know who he is. The conga line of contemporary Australia moves on through the glass labyrinth towards Ned Kelly’s helmet and Sir Donald Bradman’s cricket bat.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.