A Storm and a Teacup

During a lull in the fiercest weather event the south-east of the continent has seen in thirty years – we call them ‘events’ these days, as though someone’s putting them on – I went out on a Sunday morning and bought myself a book.

I should tell you that we live on an acre in the country one hundred and twenty-five kilometres south-west of the city. We moved here two months ago after another unsuccessful attempt to love – and afford – the city. We used to live in the mountains. Then children came, and I needed to find the kind of regular work that feeds a mortgage and a family, and which one finds more of in a city. We moved to a terrace house in the inner city and tried to like it. But I’m not much good at the kind of work you have to do to afford the kind of oversubscribed and overlit life the city wants you to lead, and every day in town was another day I couldn’t see out to any kind of country, and every day I seemed to become less like the man I thought I was.

So here – to keep it trim – we are in the landscape again. The house we found was built for the man who ran the dairy for the big property from which our acre has since been cut. The house has grown in the hundred years since it was that first dairyman’s home. It has four bedrooms now, its weatherboards are a nice dusty yellow, and its roof is clad in corrugated iron. It is a plain house, but pretty, and it is set about with rose bushes and mature trees, and it is more than enough for us.

But the real reason we bought the place – apart from the paddocks over the fence and the space around us and the cool air above, and apart from the fact we could afford it – sits down the back between the silver poplars and the oak. We moved here because of a cowshed. The cowshed is a little older than the house, and it is the reason the house is here. It is made of brick, rendered now and painted the same kind of yellow as the house. According to Ross, who came the other day to dig a trench to bring the telephone wire down from the house, the cowshed is a four-stand walk-through, and it would have milked sixty head twice a day one hundred years ago. Since mid-March it is where I have sat and worked, and I am sitting there now – writing this – in early June. Across the lane the elms have stopped being yellow and stand bare against an acid-clear winter blue sky. The ground smells of poplar leaves and the aftermath of rain. The light is failing; soon I must go and lock the hens in their coop. Down in the paddocks some heifers bawl. Soon the frogs will start up along the Wingecarribee, which snakes through the pastures and the willows and the birches down there, a quarter mile from where I sit.

I am in Australia, though it’s not easy to tell. No eucalypts here. No sheoaks in sight. Nothing to place me here except for the name of that river and the way a mob of Eastern Greys bounds away in its desultory panicwhenever you get close to them in the paddock by the river, and the fact that it is winter in June, and the way right now the possum drags its world-weary self into the nest it calls its own in the ceiling above my head. Something antipodean – which has nothing to do with ‘Australia,’ that abstraction, of course, but everything to do with the way this place belongs to the natural history of this bend of this particular river on this particular continent under this bit of heaven in the present geological era, the Holocene, doomed and beautiful era of men – something antipodean, more than a scent, less than a voice, something close to a sensibility, is immanent here, in the face of so much circumstantial evidence that this cowshed is set down somewhere in West Massachusetts or The Cotswolds. And I don’t believe for a minute that I would write the truth about this place, nor would I write truly from this place about anything, if I didn’t catch in my syntax and diction something of the cadence of that local Wingecarribeean intelligence, including the way it plays among these colonial cows and cowsheds, these immigrant trees and grasses and women and children and men, such as me, sitting here in my post-pastoral shed withmy pale skin, my Cornish surname and my Apple computer.

Australia, the driest continent on earth after Antarctica, is drying out. Down in the southern half of the island, we’re nearly ten years into a drought that’s starting to feel like the future, global warming being what it is turning out to be. The dam, for instance, that keeps Sydney in water, is below thirty-five per cent, and it’s not been above fifty for as long as I can remember. In the place where I have come to live, a panicked government has slyly approved the pumping of the Kangaloon Aquifer into the river system that stocks that dam – a plan that threatens to wreck the pastures and swamps and brown-barrel forests of the basalt hills under which the aquifer runs. Such is our growing desperation. For the skies have dried up, and the ground below is perishing. In five years we will have a desalination plant turning the Pacific Ocean into potable water. But we’ll be needing quieter and more radical solutions than that: like, for instance, the sclerophyll habits of the native trees – their ethic of restraint.

‘Australia, the driest continent on earth after Antarctica, is drying out’

But in the meantime, we have been dancing and voting and praying for rain – and we’ve been doing it too well, it seems. For suddenly, on the very afternoon of the eve of last weekend, a long weekend, a low-pressure cell settled over a large tract of the east coast and dropped 200-odd millilitres out of cyclonic winds over the next two days. Trees fell, houses fell, roads fissured, and cars upon them and families within them were washed away. Farming land and shopping malls and entire suburban streets were inundated.

Things were pretty calm, by comparison, here along the Wingecarribee. I went out Saturday night and strung a tarp over the chicken coop, because I hadn’t got around to getting someone to get around to patching the leaky roof, and the girls were having trouble staying dry. I was wetter than they’ll ever get by the time I had fought the blue tarp placid in the gusting winds and pinned it with bricks to the roof. And my cowshed leaked; the winds were carrying rain from all points, including, apparently, north, and some of it got in under the big barn door. I came in Saturday morning and found a shallow kind of estuary making a muddy kind of sea of the rug on the concrete floor. I mopped it up and plugged the gap with an old towel and got a fire started in the stove and thanked the household gods that the good old structure, home now to my library as well as my work, was as sound as it looked, and I got on.

By Sunday the worst was over – though not in the Hunter, where floods were just making ready to come downstream. The system that had caused all this had blown out to sea to make its peace. But a trough was coming in behind it, so I figured we had a few good hours to take our cloistered selves and our cabin-feverish children outside. The paddock is normally where I would have started. The paddock and the river. To check on the ducks and the white-faced herons, the horses and the roos. ‘Can you take me to the paddock?’ Henry, who is four, asks whenever I return to the house from the shed. This morning he was more eager than ever because he could see from the house some impressive puddles down there in need of being splashed. But right there – that was going to be the problem with the paddock, even in good rainboots. So instead, we took a drive to Berrima, and after horsing round at the village shops while Maree discovered bargains, we drove some more and landed up at Berkelouw Book Barn.

Now, I don’t need any more books. But you don’t have to need them. I found some nice old Zane Greys and a Paul Auster and a Larry McMurtry, but I left them. I found two volumes by a good poet who used to live close by, one of them named – aptly – Berrima Winter, and I bought them. And then, after an hour’s bibliophilic shambling about the wooden floors, face out on the counter of the café, where we had bought off the boys with a milkshake, there it was, the thing I didn’t know until then I had been looking for: The Book of Tea.

The book was a small work of art, humble and finely made and useful like a piece of anagama pottery: a small hardback, bound in white cloth, the title gold embossed on a black panel, and textured brown endpapers inside. This was an object incarnating an idea, and the idea, happily, was what the book was about. The Book of Tea is a Zen classic, written a hundred years ago by Okakura Kakuzo. What Okakura, like Basho well before him, wanted us to know was that the tea ceremony, performed, of course, mindfully, might be not just a metaphor but an actual practice – right up there with painting and poetry and solitude – for mindful living; for a well-made, dignified and responsible kind of life, and for what Okakura called a beautiful death.

What he meant by that was not so much an actual (good) death but a kind of dying to one’s meaner self – a making of one’s life, as Sam Hamill glosses it in the introduction – part of a greater work of art. And that greater work of art is the way that nature goes. ‘The first task for each artist,’ Basho wrote in Knapsack Notebook, meaning not just the making of art but the making of a good, true and beautiful life, ‘is to overcome the barbarian or animal heart and mind, to become one with nature’.

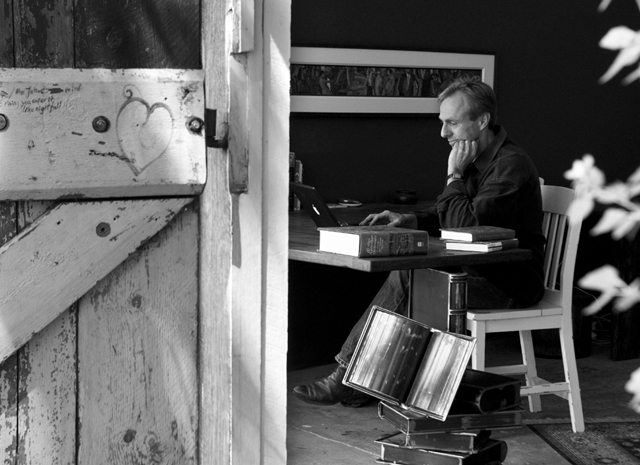

Mark Tredinnick in the cowshed (photograph by Tony Sernack)

Mark Tredinnick in the cowshed (photograph by Tony Sernack)

And so one might live well and, for that matter, write and paint and parent and garden and keep the chooks dry and mop up the cowshed well by adopting ‘tea mind’, by living as though one were making and sharing a good cup of tea, a thing one has learned to make so well – sticking at the task and bringing all one’s attention to it – that the enactment becomes easy and natural. As though it belonged to nature herself. ‘Learn the rules,’ Basho advised artists, poets especially, ‘and forget the rules.’

‘Tea mind’, if I have understood it, describes pretty well how I aspire to live here and how I would like to write and how I would like quietly to change the world’s mind. And I am pretty sure I’m going to fail, though the failing and carrying on anyway is part of the ethic The Book of Tea describes. Which goes something like this: to live conformably with the rest of creation; to live modestly, mercifully, truly; to say nothing, if one can’t say something that helps; to do nothing, if one can’t do something that helps. And there is an aesthetic that goes with it: the simple vernacular beauty of the little white book and the tea ceremony it describes; of the cowshed and the paddocks in winter. I was always attracted to the idea of living mindful of one’s small part in the larger natural world. In the story of one’s habitat. In the narrative of evolution. In the geologic epic of the world. I like the idea, though I always stumble at the practice, of living as if I really were a part, like the wrens in the hedge right now, of the place in time, attuned, as Basho put it, to ‘nature through out the four seasons’ (not that there are four seasons here).

‘I was always attracted to the idea of living mindful of one’s small part in the larger natural world’

The secret to the beautiful life, then, is tea; the secret is attunement to a larger world than one’s self; the secret is perspective; the secret is humble, open-eyed, big-hearted, tough-minded awareness.

I paid for the milkshake and coffees, and I bought the book, and as we drove home into the returning rain, I began to wonder how tea mind might look in weather like we had just had, in weather not yet done. What would the tea-mind practitioner look like, for instance, having drunk their tea and walked down to a cowshed, sending some e-mails as the storm resumes outside, and writing some poems and later, perhaps, doing something about trying to persuade the government to stop drawing so mercilessly on the Kangaloon Aquifer just over the ridge – what would one look like if one’s actions were attuned to a once-in-thirty-year weather event like this? What would tea mind look like in cyclonic mood? What would Hurricane Katrina mind look like, for that matter, and what good would it bring?

Nature never was temperate, and she is not getting any calmer. A life pursued at one with nature would not be the tranquil endeavour The Book of Tea might make one imagine. Would a beautiful life and death include behaving now and then like a turbulent low-pressure cell, like the waves that washed a tanker onto Nobby’s Beach and forced thousands of Novacastrians out of their homes and washed nine people away in their cars and killed them?

Okakura has an answer:

Those of us who know not the secret of properly regulating our own existence on this tumultuous sea of foolish troubles we call life are constantly in a state of misery while vainly trying to appear happy and contented. We stagger in the attempt to keep our moral equilibrium and see forerunners of the tempest in every cloud that floats on the horizon. Yet there is joy and beauty in the roll of the billows as they sweep outward toward eternity. Why not enter into their spirit, or, like Liethse, ride upon the hurricane itself?

I am pretty sure that Okakura’s idea would bring small comfort to the extended family of a mother and father and three young children whose car fell into a fissure opened in the Old Pacific Highway last Friday in the thick of all this by the falling rain and the rising creek and carried downstream to their deaths. Nature, whether you are at one with her or not, is blind, like justice. Riding the hurricane can kill you, and the dying won’t always be beautiful. There is a quietism in tea mind – there is a kind of resignation implicit in the very ethic I aspire to – that troubles me. But as in nature, so in human life – and so Ecclesiastes, that other great book, says – there are storms and there is death; there is violence and there is peace; ‘there is a time for every purpose under heaven’; there is a time, for instance, to weep, and a time, a bit later, to laugh; there is ‘a time to break down and a time to build up’.

So I can see how tea mind – place mind, if I may translate Okakura loosely, even cowshed mind – might include rage and protest, rightly steeped, of course, and poured precisely for whom and only for whom it was meant. When marching on the Capitol, I hear Okakura intone, just march on the Capitol; when writing nature poems, just write nature poems; when changing the baby, just change the baby; when changing the world, just change the world. Master the steps required for that one task, and perform them in good time, as though they were the most natural thing in the world – and the only thing on your mind right now.

The weather event played right through the weekend – it still plays – in newspapers and on television as a story of calamity: holidays ruined, property damaged, hopes dashed, lives, worst of all, lost. Disaster is one way, perfectly understandable, to characterise the weather. And again, it is all very well for me, high and dry in my cowshed in the placid Southern Highlands, to say this, but to tell the weather that way is to see the world from an alienated, merely human perspective; it is not to see things whole; it is not to observe the world with tea mind. Ours is, after all, a continent in drought; the land – and we upon it – need the rain. And we need it to come as emphatically as this; the groundwaters are drying out, and only such heavy rain, again and again, will bring them back, if they are ever coming back. We should be giving thanks, while we also help and comfort those who have suffered.

The world, we must not forget, has changed. It was always thus, of course. That is the nature of the world. But lately it’s been doing it fast, and it looks like we are largely to blame. Where I live, the world has got drier; and in many places it is getting sporadically stormier. Like this weekend. This is nature now. This is a new kind of season, and we had better get used to it. There is going to be more hurricane-riding before we are through. ‘The art of life lies in a constant readjustment to our surroundings,’ Okakura advises. So let’s adjust; let’s see the fierce new world for what she is; let’s ride her and rein her in how we can.

‘Let’s adjust; let’s see the fierce new world for what she is; let’s ride her and rein her in how we can’

When I interviewed David Suzuki last year, he told me that the world has, in his estimation, ten years to change its habits fundamentally – to the tune of ninety per cent, which is to say, almost completely. We’re going to have to scale things back. Drinking tea will not be enough; but it does speak of moderation, a thing we are going to have to master again. The modesty and simplicity of the ceremony remain a powerful metaphor in these immoderate and apocalyptic times. We need to use less of everything, Suzuki explained to me with alarming equanimity (‘tea mind’?) and assurance – less energy and water, in particular, in everything we do (writing books, warming houses, travelling, lighting our lives, growing grain, raising cattle, raising children, fashioning clothes, shipping everything, you name it) if we are to avoid tipping the earth into the kind of unstoppable atrophic chaos Al Gore’s film, An Inconvenient Truth, so vividly depicted. And we need to do it fast and stay calm while we do.

The good news is we have the techniques and the wherewithal, Suzuki and others say, to change our ways to that degree in just about every field. The bad news is what it always was: everywhere in the developed and developing world there is an overwhelming lack of political, mercantile and domestic will. Prosperity is a drug of addiction; denial and lethargy are two of its side effects. So perhaps the best news of all is also the worst: we are running out of oil. Nothing may teach us to live more slowly than running out of gas. And when the oil is gone – and later the coal – we will, if it is not too late, stop fueling the engine that is overheating the system.

The Book of Tea speaks of the ultimate virtue of attunement, of living at one with the way things go. Harmony is the organising metaphor here. The phrase ‘at onement,’ which grew out of a Middle English expression, used to mean the same thing – harmony. ‘Atonement’, though, which that phrase evolved into, means not just harmony but a process of reconciliation, some kind of putting things right again, and – importantly – some kind of sacrifice or suffering. If we want to live sustainably, if we want the world to keep us, and more particularly our children, we are going to have to surrender some of what we have; we are going to have to give something away. It is going to cost us, and so it should: it is worth the world. Someone has to suffer, and it might as well be us.

We need, more than anything, to learn the elegant restraint, the modesty, of the tea ceremony – a thing the eucalypts already know. And we are going to need to persist. Ritual repetition of modest gestures is what the tea cere-mony, like all Zen practice, consists in; it is what it teaches; it is what the world needs now, possibly more than love. Unless that is what love really is.

The tea ceremony – ‘teaism’, as Okakura calls it – ‘is a worship of the imperfect.’ To live well is to essay something within your gift and to work at it until you have got it more or less down. Perfection, in other words, is not necessary, even in these urgent times. We are going to fail the world long before the world fails us; it is a question of how badly or beautifully. What is compulsory is effort: sacrifice and discipline and selflessness.

One cold night this week, after the stories, some of them recited by the boy, some of them read by his mother, Maree was talking Henry to sleep, and she was talking, as mothers sometimes will, about how the boy had come into the world and how it had made her glad. Nearly asleep, the boy asked her, ‘What is the world?’ What, indeed.

‘What is the world?’ is the question we may be here to live. Learn the world, Basho might almost have said, and forget the world. That is to say, become not merely yourself; become, where you are, what the world is. Celebrate the world; it is beautiful and terrible. Like God; like one-self. Come into the world over and over again.

And because the world, in its physical manifestation, is also what we drink and breathe and eat and walk and work upon, we had better not just observe it; we had better husband and conserve it. And try to rein ourselves in.

After the rain, we had four hard frosts; four cold and brilliant days. Now it is raining again. Steadily this time. Good rain; nothing violent. By mid-month this is already the wettest June since 1964; 350 millilitres of rain have fallen, and this is only the start of what we need. The Wingecarribee has broken its banks and made a floodplain of the pastures just below me. But still there is hardly a word of welcome for the rain. Nothing much is said in the press or on the streets of the virtues of this drenching (except at last today a mention at the bottom of the nightly news that our dam may soon be up to close to fifty per cent capacity.) We seem to need all our stories to speak of ourselves. We want drought and flood; we want tragedy and loss; we want heartbreak and fairy tale and comfort. The land is the big picture, and we forget to paint it. It isn’t news, of course; we are, as ever, the news.

So the rain runs in the papers as the quantum of damage, as contested insurance claims, as heroics and adversity, and it is all those things, and, had I lost my family or farm or library, my teacup might be stormier. But mostly the rain is itself; that is the story, and it would behove us to listen. I have been hearing it all day on the roof and in the gutters; I’ve been seeing it in the hanging lichens of the poplars. The trench Ross dug across the yard has subsided. The boys step in it, and Henry gets stuck there, right up to his knees. The world has got hold of him.

At dusk I wade out to the car and drive – there I go driving again – with our baby girl to the post office to send a birthday card to a nephew before it’s too late. Lucy falls asleep in the car on the road; that was part of the plan. I am home now, and I have carried her to her cot, and I hope she’s sleeping still, but I have come back here to write on, and it rains on, and Maree’s in the house feeding the boys, and night is falling along the Wingecarribee. My wife knows a whole lot more than I ever will about the art of tea and the business of patience and the repetitive performance of small, good, necessary tasks. But something in me wants to write today. So here I sit again at small, difficult repetitive gestures of my own, in which I persist in a cowshed, noting ‘the beautiful foolishness of things’, in case it helps. And beside me rests The Book of Tea.

When I came upon The Book of Tea, I was wrestling with a poem. I didn’t know – I still don’t – if it is an especially good poem. But I knew I had to write it, and I had been sitting at it in the shed, picking it up and putting it down between other obligations all week, in every kind of weather, most of it cold. That Sunday morning in the bookbarn, I knew my poem was two stanzas short. A poem is an equation, among other things, and mine hadn’t quite come out. I was aware, too, that my poem was still looking for whatever it is that tautens a poem, that tightens its screws – a line of thought older and more beautiful than I had discovered working alone in a cowshed; it wanted, perhaps, a hit of caffeine; the medicinal fragrance of a cup of hot black tea. And when I opened the tea book, it happened.

‘I found in the book what my poem had been trying to help me think – about the way I want to live and work, here by the Wingecarribee, or wherever, until I am done; I found what I had been trying to say’

I found in the book what my poem had been trying to help me think – about the way I want to live and work, here by the Wingecarribee, or wherever, until I am done; I found what I had been trying to say. It wasn’t the only answer in the only words I will ever need to the best question I’ll ever ask; half the books in my library know the same thing the tea book told me. Some of the books of my grandfather’s preaching Bible lying over there on the third shelf up have been talking to me thus all along. But it was a good answer, shapely and wise. And timely. And not only for my poem.

I found in The Book of Tea an economics and a moral geometry – to use Okakura’s phrasing – for the slow and mindful, engaged and grounded life I aspire to here, and at which, as I say, I will almost certainly fail. The tea ceremony, writes Okakura, ‘is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life’. Maybe that is what I am down here working at tonight, my feet cold in their boots, the rain falling hard again on the roof.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.