'Missing from my own life' by Elisabeth Holdsworth

About ten years ago I was interviewed on Irish radio on a matter entirely unconnected with writing. The first question the interviewer asked me was, ‘Is that yourself, Elisabeth?’ This ungrammatical question struck me as both hilarious and pertinent. I don’t remember much about the interview except that leading question.

‘Is that yourself?’ In 1959 the sociologist Erving Goffman wrote a famous book called Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life. Goffman hypothesised that we are all actors on the stage of our own lives, that we present convenient and expedient personae according to the occasion. In hindsight Goffman’s proposition seems obvious, but in 1959 this was groundbreaking stuff, with particular relevance beyond sociological interpretation to the dramaturgical. Indeed, Goffman explained his thesis using the theatre as a model. He proposed that everyday life is a staged performance. Thus, the front of house is where the public performance of our lives is managed. Backstage contains the parts of our lives that are inaccessible to a wider audience. Yet, it is backstage where the most interesting things happen. I come from a background in the social sciences. To me, the act of narrating a memoir is a front-of-stage performance and memory, the handmaid of memoirs, is dragged out from backstage as a supporting cast. However, as any social scientist will attest, memory is the most unreliable component of the psyche.

‘In telling the story of my ancestors, my attempt at the memoir genre proved self-defeating and creatively stultifying’

In telling the story of my ancestors, my attempt at the memoir genre proved self-defeating and creatively stultifying. Rather than helping me to explain why I had gone missing from my own life for the best part of thirty years, I found that I was disappearing into a fault-line between what I wanted to reveal and what needed to be kept hidden. The final result was a front of stage performance. The curtains to the area backstage, which should waft enticingly, were tightly closed.

This is not unlike the dilemma that Günter Grass explored in his purported memoir Peeling the Onion (2007). Grass’s decision to reveal that he was briefly (and ineptly) a member of the notorious Wafen SS at the end of World War II aroused such controversy that it derailed the important points he made about memoir: namely, the cohesion and dissonance between Dichtung und Wahrheit, fiction and truth; the way in which a backstage story can be told front of stage.

My full name is Elisabeth Miriam Esther de Rijke-Nassau. I am a medieval dinosaur. When I die, a DNA coiling back to Charlemagne will be declared extinct. In 2010 others who claim a more indirect descent from Charlemagne will gather in a place called Vianden, in Luxemburg, to celebrate one thousand years of identity as the Nassaus. Vianden, a castle in the air, was abandoned in the seventeenth century but reconstructed in the 1960s. It is where my ancestors first established their identities as warlords, dukes and princes. Now it is a tourist site.

The Nassaus led the revolt of the Low Countries against the Spanish in a war that lasted the worst part of eighty years, ending in 1588. A century later, another Nassau, William of Oranje-Nassau, became king of England. At the Battle of the Boyne he defeated his father-in-law, James II, the last Catholic king of the English. Among William’s legacies was a divided Ireland and the wearing of the Orange in support of the Protestant cause.

The author's parents on their wedding day, 1935 (photograph courtesy of author)

The author's parents on their wedding day, 1935 (photograph courtesy of author)

I was born on a freezing day in January 1947 in a place called Middelburg, on the island of Walcheren, the most south-western province of the Netherlands. Middelburg, or Middelbroch as it was known in the Middle Ages, was founded in the twelfth century by Elisabeth Kunigunda, daughter of the king of Thuringia and wife of Wolfert of Nassau. My grandfather, who had many titles but preferred to be known as ‘The Lord of the Islands’, registered my birth the same day. As if he knew I would be the dynasty’s full stop, he added to my birth certificate the title ‘The Lady of the Islands’. The matter of titles is a minefield of arcane conundrums. Only someone born into the family can be known as the Lord of the Islands. As I come from an unbroken male line, there had never been a ‘Lady’ before.

A few days after my birth, I was decked out in eighteenth-century lace in preparation for my baptism. The tradition of the Calvinist sect I was born into dictates that one of the godparents should carry the child to church. My godfather, Prince Bernhard, the German-born son-in-law of Queen Wilhelmina – a war hero like my father, who was his close friend – emerged from my grandparents’ house, took one look at the snow and ice in the street and removed his army greatcoat. I was carried to my baptism wrapped in the same coat that Prince Bernhard had worn when he accepted the German surrender at Wageningen.

This story, this image, is so vividly imprinted on my psyche that I can feel the cold. I can visualise the streets, the wasteland of the dead city which had been consumed by the fire of blitzkrieg; then flooded and sunk in the liberation of the Netherlands. Logic suggests that it is impossible to remember one’s infant baptism. Nevertheless, the story exists, transported somehow to my memory banks.

On my second birthday I contracted rheumatic fever and nearly died. My mother had been badly affected by the war. She had spent two years in Dachau, betrayed by one of my father’s brothers. For long stretches of my childhood she disappeared into a sanatorium. My father, a dijkes engineer in charge of the reconstruction of our province, was of necessity absent for much of the time. For the next four years I was largely brought up by my father’s aristocratic parents, who had given three sons to the war, and by my mother’s parents, who were illiterate Jews and from whom my paternal grandmother, looking for servants, had virtually abducted my mother when she was ten. These four people, from such different backgrounds, gave me the greatest gift – unconditional love. To them, the sole child to be born after the war, the only survivor of both families, I was the centre of their fractured universe.

In 1953, on another bitterly cold January day, a great storm surge in the Atlantic produced the highest tides in living memory. At midnight the dijkes around our island, which had been deliberately destroyed by the Allies and the Resistance in 1944, and which had been badly mended after the war, could not withstand the force of the sea. Eighteen hundred people died that night, thousands more in the following months, of pneumonia, influenza and heartbreak. Among them were my grandfather, the ‘The Lord of the Islands’ and my grandmother, François, his ‘Lady’.

I remember that night in 1953; the profound silence before the dijkes of Zeeland broke one by one lives as strongly in my brain as the memory of being carried to my baptism by Prince Bernhard. These two memories survive as indistinguishable entities within my psyche. Yet one of those memories is a psychological impossibility.

By 1955 my father was a disgraced and bitter man. He blamed the government for neglecting the rebuilding of the dijkes. He lost the patronage of the royal family and, most importantly, his friendship with Prince Bernhard. Over the next few years he rented all of our properties and arranged a two-year exile for us in a place he called ‘New Holland’. He would never call Australia home.

‘There is a narrative arc in Australian migrant stories which prefers you to arrive penniless, make a success of your life and refer to yourself ever after as a proud and grateful Aussie’

There is a narrative arc in Australian migrant stories which prefers you to arrive penniless, make a success of your life and refer to yourself ever after as a proud and grateful Aussie. My parents and I arrived with a shipload of possessions, a suitcase full of titles and enough money to buy a fairly grand house in an upper-class Melbourne suburb. Less than two years later, my father was dead and my mother and I had an unpleasant encounter with poverty.

In 1975 my mother was killed in a car accident. I was the driver of the car and walked away physically unscathed. The memory of that dreadful moment of impact, the severing of my mother’s life, is one that can never be dislodged.Two years later, I married and became Elisabeth Holdsworth, effectively erasing my previous life. I researched my family from time to time, particularly when I was stationed at NATO Headquarters in Brussels. I rarely spoke about my family. Although I was physically close to the Netherlands, I avoided going there. When I returned to Middelburg in 2005, it was the first time I had been there since 1959.

In my professional life I was required to be discreet. Closing the curtains firmly on anything going on backstage became habitual, perhaps pathological. My going missing from my own life suited me and my masters. And that is how it remained for the next three decades.

In 2005 I learnt that my aunt, my last blood relative, was dying in the Netherlands. Katrien, my father’s only sister, had been a lady-in-waiting to four queens: Emma, Wilhelmina, Juliana and the current monarch, Queen Beatrix. Katrien was sent to court in 1920, with every hope that she would attract the attention of an aristocrat and marry well. My family had considerable wealth from properties in Indonesia, and Katrien had a huge dowry. Yet she died in 2005, having never married. At court she had been handicapped on two counts: her mother was a member of the re-reformed Calvinist sect, frowned upon by the royal family; and there was a rumour that my paternal grandmother, Katrien’s mother, was part-Japanese.

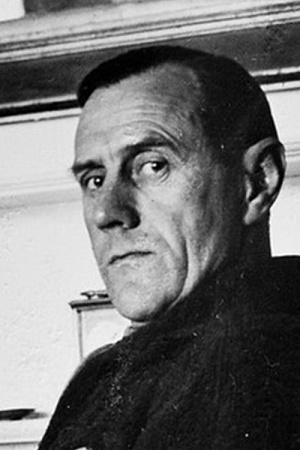

Her name was François de Rijke. Her family may or may not have been related to my father’s. The story that came down to me was that her French-sounding first name, her dark eyes, her black hair (which my father and I inherited), were due to Huguenot ancestry. Her father was Johannis de Rijke, who lived in Japan from about 1873 to 1903. Johannis is known to the Japanese as the hero of Kiso for his work in the reclamation of the Kiso Delta near Nagoya. He was a secretary of state and close confidant to the Meiji emperor – the only Westerner to achieve this status in Japan.

Johannis returned to the Netherlands in 1903, having been decorated by the emperor of Japan and knighted by Queen Wilhelmina, yet when he died in Amsterdam in 1911 he was buried in an unmarked grave. According to her marriage papers, François was born in Nagoya in 1879. She did not exist as François before her marriage to my grandfather in 1899. I have no idea who her mother was or what her true given name was. I only know that when François married my grandfather the Meiji emperor gave her a ring, a heavy gold band with a large cornelian set in a coronet. The story I received was that Meiji gave this ring to François as a sign of respect to her father.

‘Is that yourself, Elisabeth?’ I hear my Irish interlocutor ask.

On the face of it I have material enough to write a memoir, maybe several. In another way, I don’t have nearly enough. Before abandoning the memoir process completely, I read many examples of the genre. To someone trained in the social sciences, Goffman and his theories on the presentation of the self had made too deep an impression for my writing to find a comfortable niche within the genre. I was torn back and forth. If I ditched the memoir process, how was I to write the stories entrusted to me?

J.M. Coetzee’s eponymous character Elizabeth Costello declares: ‘There must be some limit to the burden of remembering that we impose on our children and grandchildren. They will have a world of their own, of which we should be less and less part.’ Quite! But what if one is the full stop? Do I have a responsibility to history, to my ancestors, and who gives a damn anyway? Why not just close the curtains and shuffle off?

A bust of Johannis de Rijke (1847–1913) on the island of Walcheren (photograph by Elisabeth Holdsworth)

A bust of Johannis de Rijke (1847–1913) on the island of Walcheren (photograph by Elisabeth Holdsworth)

The decision to write in another way was ordained in Middelburg in 2007. It was made for me by my ancestors and by that uncomfortable companion of one’s life – the psyche. My husband and I were staying in an upstairs apartment of a narrow house in a street called the Joodengang, Jew’s Alley. The stairs to our rooms were no more than a ladder, which could only be negotiated backwards. At times during my life I have been afflicted by sleepwalking. I had spent days trying to write the memoir. It was proving so elusive that even a title refused to reveal itself. My nights had become peopled by horrible dreams of my ancestors rising out of their crypts with raised arms. One night my husband woke me as I was about to descend the ladder frontwards. Had I done so I might have been badly injured, or worse. My husband is a phlegmatic man, not given to outbursts. ‘Will you stop with that bloody memoir before you kill us both!’ he shouted.

I persisted a little longer, and found two apparent memoirs which proved useful.

Michael Ondaatje, in his memoir, Running in the Family(1982), makes the following comment, which sums up my dilemma: ‘Truth disappears with history and gossip tells us in the end nothing of personal relationships.’ In the acknowledgments, Ondaatje makes this extraordinary statement:

My family ... had to put up with compulsive questioning ... hearing again and again long lists of genealogies and rumour ... I must confess that the book is not a history but a portrait or ‘gesture’. And if those listed above disapprove of the fictional air I apologise and can only say that in Sri Lanka a well told lie is worth a thousand facts.

Ondaatje’s fictional air and gesture towards memoir is a work of art. My attempt at something similar was rubbish and quickly abandoned.

Günter Grass dubs memory the handmaid of memoir. In his view, very appealing to a social scientist, memory is subject to conflation, distortion, misperception, deception and ambition. In Peeling the Onion, Grass repeatedly shows how the stories arose out of real events, and illustrates how the lines became so blurred that he cannot say, or will not say, where truth deviates from fiction. The origins of The Tin Drum (1959), he says, lie in a postwar stonemason’s yard, the winding path to art, and the narrow track between literature and reality, Dichtung und Wahrheit.

Grass uses the metaphor of peeling an onion layer by layer to reveal the core of his memoir. But what is the core? Grass, also a graphic artist, provides the etchings in the book. The endpaper shows a closed onion, with a baby onion next to it – not, as one might expect, the fully flayed vegetable.

I read Peeling the Onion not as a memoir but as a commentary on the memoir genre, with its inherent complications such as omission, exaggeration and problematic memory. I absorbed two important lessons from Grass: a way of writing while treading that narrow path between Dichtung und Wahrheit; and another more important moral lesson. In the world I grew up in, the suffering of the German people in the immediate postwar period was a matter of indifference to us. Grass describes how his mother, who was not at all sympathetic to the Nazi régime (quite the opposite), was raped repeatedly by the Russian liberators who helped free the German people from themselves. Mrs Grass died of cancer five years before the publication of Tin Drum.

This I believe to be the true core of Grass’s work: to make us aware of that postwar period that the victors have chosen to ignore.

Grass and Ondaatje had something I did not possess: people – characters – from whom they could draw those small and large details of their lives. With the exception of my aunt, all the characters of my life had died decades ago. Time proved to be the final thief as I tried to write my memoir.

‘Is that yourself, Elisabeth?’ That medieval dinosaur searching for some evidence that we existed at all?

My mother was betrayed to the Nazis by my uncle. Had he revealed her Jewishness, not just the fact that she was the wife of a Resistance leader with a price on his head second only to that of Prince Bernhard, she would probably have died in the concentration camp. But she escaped, and after the liberation, amid the turmoil, my father executed my uncle for his treachery.

Despite everything, my mother was one of the wittiest people I have ever known. (Once, when a gauche boyfriend of mine asked her if she had been to university, she replied, ‘Yes, the University of Dachau’.) She was also immensely intelligent and brave. But violence was a part of her life too. As I was growing up, my mother wasn’t insane but she was consumed from time to time by a rage at the hand that fate had dealt her. She beat me, even when I was very ill. She struck me for the last time when I was sixteen. I was vacuuming at the time and she had just hit me across the back of the head. I lifted the end of the pipe and said to her, ‘If you ever hit me again, I will kill you’.

The castle of Vianden at Luxemburg (photograph by Elisabeth Holdsworth)

The castle of Vianden at Luxemburg (photograph by Elisabeth Holdsworth)

Fifteen minutes later I left the house, not to return for a year. I didn’t go very far. I moved in with a man who lived around the corner. He was a psychiatrist and homosexual. I am speaking of the mid-1960s. The word ‘gay’ was not in common use then, though other descriptors and attitudes were. My mother knew where I was. She, bless her, had an imperfect understanding of homosexuality and thought it meant that he was sterile, that I wasn’t therefore in danger of becoming pregnant. How right she was.

‘My mother and I were united in the belief that this damaged, haunted man deserved our unconditional affection’

I owe this psychiatrist my interest in human behaviour. For a year my mother and I talked through this man. She misunderstood the backstage aspects of homosexuality and frankly didn’t care. My mother and I were united in the belief that this damaged, haunted man deserved our unconditional affection. Gradually, after many travels, many adventures (none of which I am prepared to discuss at this time), we became close again. In my twenties we shared a flat in Melbourne. Mother declared that there be only one house rule – that whoever was there for breakfast was there and that was that. Needless to say, the friends were always hers, not mine.

I can never atone for the car accident which took my mother’s life, but I can try to make her live on the page. In fiction I can make sense of her rages at the many unfair throws of the dice. In fiction I can speak about my psychiatrist friend, who committed suicide in 1975, the same year my mother died. And through fiction I can examine my grandmother’s life and explore the forces that made her recreate herself into this persona, ‘François’, with her rigid adherence to the most fundamental tenets of Calvinism, presumably to conceal her Japanese past.

In 2010 this dinosaur, this relic of medieval riff-raff, will attend some fine parties in Luxemburg, at a castle in the clouds called Vianden. I will also host some grand affairs in a place called Middelburg, which has been rebuilt to an approximation of what it was before the war. That year, for what will probably be the last time, my home, Toorenvliedt, the fourth castle built on the same site since the twelfth century, will take centre stage. In 2010 I will probably be the only one to remember that it is also the centenary of my parents’ birth.

Both Vianden and Middelburg hold the myths, the rumours, the truths, the conflations, the erasures and all the rest of the baggage that surround my ancestors. My heart belongs in these places, yet they are both recreations of something they once were, or hoped to be. Vianden and Middelburg are as real as film sets. I would like to think that ultimate irony would appeal to that insightful sociologist, Erving Goffman.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.