It should be so, it must be so

David Walsh is a tease; he enjoys wordplay. The founder and owner of the Museum of Old and New Art (he prefers Mona, not MONA) concedes that his private playground is entirely a matter of self-gratification, like ‘the sin of Onan’. Hence the cheeky titles ‘Monanism’ for his inaugural exhibition of some 460 works, and Monanisms for the beautifully produced picture book of 115 selections from the collection (Monanisms: Museum of Old and New Art, $80 hb, 378 pp, 9780980805802). Many of the latter are not included in the inaugural exhibition, and will be presented later.

By way of an exhibition catalogue, which Monanisms is not, there is a new-technology option. Substituting for labels, an iPod device, called The O, contains information that you can email to your home computer. My printout checklist of sixteen pages included a lot of accidental duplicate hits, and three pages of ‘Missed Works’.

The book is a bibliographic tease. The colophon assigns it to a corporate author, ‘Museum of Old and New Art (Tas.)’. Another page identifies ‘Contributors: David Walsh, Elizabeth Mead/with: Jane Clark, Damian Cowell, Gregory Barsimian, Tim Walsh’. Book-buyers like to know who did what, and they eventually read that crucial research was contributed by Jane Clark, Mary Lijnzaad, and Delia Nicholls, that the editor (meaning copy-editor) was Linda Michael, and the superb designer was Leigh Carmichael.

Carmichael devised the playful Curator-Rater, an inserted cardboard disc that rotates under a perforated black page. Sixteen favourite works are named on the page, and when the underlying rotator marks a particular work with Mona’s signature colour (the in-your-face shade known as ‘Shocking Pink’ that appears in all Carmichael’s printed ephemera), its curatorial score appears in another perforation. Cassandra Laing’s drawing Darwin’s girls scored 340; Andres Serrano’s The morgue, a photograph of an Aids victim’s corpse, scored twelve. I couldn’t work out what the rating system meant. The sequence of illustrations is systematic, too, but I couldn’t work that out either.

Mead, a young staffer, wrote up most of the notes about the works from Walsh’s comments and various research sources, including interviews with artists and curators. Some works have no accompanying text, others have many pages. Walsh himself is sole author of quite a few texts, among which are a crucial five-paragraph preface, a four-page introduction, and a brief afterword. Jane Clark’s contributions are usually straight art-history essays about older works.

Mona commissioned Melbourne garage-punk musician Damian Cowell to compose fifteen songs inspired by art in the collection. His lyrics are printed in the book, and the songs, constituting an album titled Vs Art, are in an audio-disc insert. Touring the exhibition with The O, you can call up Cowell’s Melbourne burning while gazing at Arthur Boyd’s eponymous painting. American artist Gregory Barsimian provides a note about his own sculpture. The last contributor, the late Tim Walsh, was David’s elder brother; a poem of his, titled ‘A Professor of History Greets his Students’, accompanies an Egyptian figurine of a baboon.

David Walsh chose everything. He, not curatorial scouts Olivier Varenne in Europe or Jane Clark and others in Australia, made the final decisions on works bought for the collection. He decided which works would be illustrated in the book. He is thus the prime author of the book, and prime curator of the exhibition.

Walsh’s modesty about his part in the book-making, and the unusually ‘flat’ management structure of Mona, are attractive qualities. His peculiar immodesty in the crucial, brief preface is oddly endearing. He imagines his forty-nine-year-old self waking up four decades ago in the mean streets of a poor Hobart suburb:

The mirror said pigeon chest, dark hair, tiny dick, flat stomach … There is nothing in the ’burbs in 1970 … My brother says he’s insane ... I don’t eat meat mum …School, Mass, people believe in God? Unformed, uniformed girls. Is it wrong to wish I was a pædophile? I can tolerate almost everything …

I invent a gambling system. Make a money-mine. Turns out, it ain’t so great getting rich ... What to do? ... A man in a white coat ... says something like, “He is highly delusional, believes he is building a museum, changing the world”.

The preface emphasises the dark hair and flat stomach at the age of nine in order to dramatise the final illustration, David Walsh Portrait,2010, a photograph by Andres Serrano. Physiological changes are visible at forty-nine; we see the mature atheist seated full-frontal naked, gazing sullenly at the reader, with greying hair and a sagging stomach.

The ambition to change the world was not entirely delusional. Walsh has already changed hometown Hobart, and Tasmania. The place – free admission helps – is abuzz with demographics seldom encountered in art museums. Sixteen-year-old free-range boys (not in school groups) are enthralled by James Angus’s dimension-shifting Mack Truck, its front jammed into the wall of a narrow corridor, its rear end visible in a nearby gallery space, but mostly missed. They have patience with video art, loll happily on beanbags to gaze at ceiling projections. One lady remarked, ‘It’s the first time I’ve mixed with lots of bogans in an art museum; isn’t that marvellous?’ By early May there had been an astonishing 163,000 visitors over three and a half months, seventy per cent of them locals, many repeat visitors; the others had come specially from elsewhere in Australia or overseas.

Museum of Old and New Art (photographed by Leigh Carmichael)

Museum of Old and New Art (photographed by Leigh Carmichael)

On the ferry back to Hobart, a stylish woman was making notes. An artist’s statement about the long corridor installation of 150 life-size porcelain Cunts…and other Conversations, ‘by Greg Taylor and friends’, is available in the Artwank section of The O. It tells that the clay had been sculpted by Greg in 2008–09 from close observation of 150 friends, ranging in age ‘from eighteen to seventy-eight …Catholic, Protestant, Salvation Army, and Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Pagans, Witches and Atheists … teachers, doctors, lawyers, accountants, writers, actors, musicians, artists, life models, students, architects and theologians … heterosexual, bisexual, lesbians. Some were virgins. All of them want one thing: for young women to be free of growing up with fear, ignorance and loathing of their bodies and sexuality.’ The note-maker on the ferry had written, ‘It was like my first time at a nude beach, surprised that every tit was different.’

Vox pop interviews in the Hobart press stated that what they called ‘the 150 vaginas’ was far and away the favourite for women. They found it ‘empowering’, but I wonder if that is a conventional response, easily offered to the most surprising work, and one of the largest.Taylor’s unusually interesting Cunts, on display in ‘Monanism’, is not illustrated or discussed in the book Monanisms.

The men’s favourite was the largest work, well publicised in advance: Sidney Nolan’s vast 1620-sheet Snake, 1970–72, forty-four metres wide. Children, less preconditioned, went for Erwin Wurm’s cartoonish anti-obesity sculpture, Fat car, 2006, a sleek Porsche Carrera encased in scarlet foam. Both are in the book, Snake illustrated in a six-page foldout, with an essay by Walsh, who says, characteristically contradictory, ‘It’s the largest modernist work ever made in Australia. I don’t know this for a fact. I could find out … I don’t need to because it should be so, it must be so … it forced a layout on the museum that now seems ideal.’

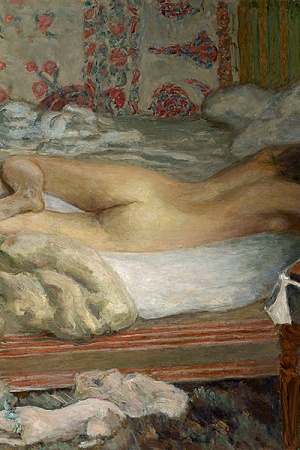

Some women have found Mona too blokey. Others have called Walsh ‘adolescent’ and ‘a nice boy’, which might be cautious appreciation of his enthusiasm. Well, the collection is a self-proclaimed, let-it-all-hang-out expression of one man’s own interests. However, some modern blokes are feminists. This one has adjusted the orthography of the museum from impersonal-corporate MONA to seductive feminine Mona. He attempts even-handed representation for women artists: sculptures by Australian Fiona Hall are conspicuous, and videos by Serbian Marina Abramoviæ.

He is even-handed, too, about gendered subject matter: a vulva in Del Kathryn Barton’s canvas Making love with love confronts you, while, nearby, you encounter inflamed penises and nipples in a series of watercolours by Balint Zsako. Barton’s painting visually rhymes the vulva with a row of pansies, and quick-witted parents of small children who enter one of the orange-red zones on the museum floor plan – ‘Parental discretion advised … Recommended for ages 15 and over’ – have an answer to questions about the Cunts: ‘They’re flowers, dear.’ Even-handedness extends to sexualities, even to primal, mythic bestiality. An ancient bronze of the god Zeus in the form of a swan mating with Leda, Queen of Sparta, is displayed near Russian artist Oleg Kulik’s 1997 performance-documentation photograph of a crouching man apparently being buggered by a homosexual mastiff. Titled Family of the future, 9, Kulik’s work was the hardest to take. It is not in the book, and The O has no comment. Google reveals that it is the climactic piece in a series where a beautiful white-skinned naked man is otherwise seen peaceably relaxed, lying among drowsy black-furred companion animals. Walsh has told us he can tolerate almost everything, and it would have helped us begin to tolerate this work if The O had provided contextual information.

The press, some years ago, latched onto a catchy remark of Walsh’s: ‘It will be a museum about sex and death.’ That is too simple. His true interest is a rather bleak atheistic belief that gods and afterlives are dangerous delusions; we are mere organisms, like plants and our fellow-animals, all of whom have to obey the biological imperatives of birth, growth, feeding, ageing, mutating, breeding, and dying. We should also continuously attempt to measure and test the world scientifically. Some of the most telling works at Mona are about mathematics and digital technology.

Considerate to our fellow-organisms, Walsh still doesn’t eat meat. The much-noticed digestion machine, Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional, 2010, a handsome industrial mechanism, suspended in the air, is fed each morning with leftovers from the Mona café, poos daily at two p.m., and is fed again two hours later. Its stinkiness is a reminder that a taste for equally stinky cheeses can be acquired. Nearby is one of Mona’s masterpieces, Jannis Kounellis’s Untitled, 1998, a seven-metre-wide metal frame containing elegantly placed sides of beef, hung on hooks; over the five days of each supply, its stink competes with Cloaca’s. Mercifully, fresh meat is hung only on special occasions, such as the ten days of Mona’s opening, or for Easter. At other times, nooses of strong rope substitute for the suspended flesh.

While we live, suggests Walsh, we should enjoy the animal pleasures of food and drink and sex and sociability. Three years ago, he initiated a summer festival in Hobart called mona foma, the second acronym standing for Festival Of Music and Art. Walsh links it to Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle (1963), where beautiful Mona follows the scriptures of the ‘Books of Bokonon’ and ‘lives by the foma – harmless untruths – that make you brave and kind and healthy and happy’. A pagan paradise is here on earth.

Some objects, but not people, achieve afterlives because of beauty. At Mona, these include Egyptian funerary wares of characterful animals, and gold and silver Greek coins, among which is a ravishing Syracusan image of the nymph Arethusa celebrating the mystery of pure spring water. There are, too, the fake Meso-American carvings that were once exhibited as originals in the short-lived Moorilla Museum of Antiquities. Now displayed in a water-filled glass case, the ‘fishy’ objects are nevertheless beautiful: harmless untruths.

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled, 1998, iron, meat, ropes, steel hooks, 352 x 782 cm, courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled, 1998, iron, meat, ropes, steel hooks, 352 x 782 cm, courtesy of MONA Museum of Old and New Art

Few paintings at Mona rise to great heights of object-and-idea, the best qualification for an afterlife. Damien Hirst’s monochrome black panel textured with dead flies is an impressive surprise. Other works by the once-hyped Young British Artists of the 1990s have begun to lose their aesthetic force. Easel paintings by Walsh’s favourite Australian, Sidney Nolan, are fine, though not the vast Snake, probably conceived for the more intimate spaces of an opera-house foyer, and too distanced in its misguided, cavernous space at Mona.

Walsh’s preface falsified the nothingness of the suburbs in 1970. Highly conspicuous on the shore beyond the young David’s Glenorchy, Claudio Alcorso’s private Moorilla estate included a vineyard and winery, a modern cube house for the tycoon–aesthete and his art, and a garden where the public came for classical music. The gambling system developed by Walsh and his fellow students of mathematics at the University of Tasmania eventually enabled them to buy Moorilla as a wine-making investment, and as a place to exhibit investment antiquities from Africa, the Mediterranean, and Meso-America. Walsh’s Mona – he bought out Moorilla from the other three gamblers when the idea for a Wunderkammer museum of antiquities mingled with avant-gardism took hold of him – has grown upon what was already the most interesting private place in Tasmania.

Walsh’s Melbourne-based architect, Nonda Katsalidis, says the exterior is ‘more a colour-matching landscape piece for the casuarinas than architecture’; his brutalist waterfront cliff face of rusted Corten steel panels and concrete honeycomb now supports Roy Grounds’s white house, which has become the foyer from which visitors descend, by lift or circular staircase, through three levels of underground museum. The ideal approach is by ferry, from which a stately flight of steps leads as if to an ancient Greek temple that turns out to be a mountain-viewing terrace with an Astroturf tennis court, where, after museum hours, Walsh plays games of geometrical skill. From there we double back with surprise to the entrance wall of the once classical house, now pasted over with a huge wavy fun-fair mirror.

The lowest level is the most extensive. After the long descent into darkness we are greeted by a bar – absinthe is available – and a scatter of bizarre fake-baroque armchairs and sofas, intended to evoke an Enlightenment salon for exchange of stimulating ideas. A great wall of live Triassic sandstone evokes geological time-scales. The first of many taxidermy works of art occur here, and others emphasising biological processes. Further along are conventional white-cube spaces intended for future temporary exhibitions. In the inaugural Monanism selection, one of these rooms is sparsely installed with little besides Conrad Shawcross’s Loop system quintet, a kinetic whirling-light piece, and Kandinsky’s watercolour Aufstieg (Rising); music and dance come to mind, the empty floor suggests a ballroom, and, on enquiry, we learn that Walsh still spends time dancing in nightclubs as well as drinking in bars.

Another white-cube space pretends to be for leftover paintings crowded onto mesh storage racks, but Damien Hirst’s dead flies are here, and the arrangement allows you to read the words pasted onto its reverse, and to inspect both sides of a double-sided Sidney Nolan. Also lurking here is a tiny pencil drawing of a mild bloke and a beer, by a little-known American, Jeff Gabel. Regardless of when you punch it into The O, it comes out at the beginning of the saved tour; we suspect it might be Walsh’s favourite work.

At the far end of this lowest level, a tunnel leads to the MONA Library, a beautiful and very respectful conversion of the Roy Grounds roundhouse built in 1958 for Alcorso’s parents as a companion to his classic square. Not accessible when the museum opened in January, it was completed and opened on 7 May.

Sculptures provide the big thrills. The Kounellis meat piece is one, and its monumentality suits the cavernous Snake space. A couple of book-related works are peculiarly Monanistic. Wilfred Prieto’s Untitled (White Library), 2004–06, is a walk-in room, lined with shelves of blank white books, which also rest on reading tables, all engulfed in blazing light – an amazement in the otherwise dark and shadowy museum; books are vehicles for mental enlightenment. Anselm Kiefer’s Sternenfall: Shevirath Ha Kelim (Falling stars: The Breaking of the Vessels), 2007, is a five-metre-high iron bookcase filled with book leaves of lead and broken glass, standing on a floor covered in broken glass. It has an outdoor pavilion to itself, reached beyond the Library. Daylight or starlight streams in the windows: light at the end of a dark tunnel from the underground museum. The title refers to Jewish liturgical song, the materials to alchemical and chemical transformation, and the image to the Kristallnacht riots of 1938, when Nazis instructed police to seize Jewish archives from synagogues in Germany and Austria, and destroy knowledge along with the Jewish race. The power of books had to be destroyed.

Walsh never graduated in mathematics. He found, as they say in such cases, that his formal studies interfered with his reading. The undergraduate computer nerd, an enthusiastic autodidact, says he consumed ‘ten books a day on ancient civilisations and science’. Walsh is, above all, mad about books.

He also loves abstract ideas. He was delighted with Leigh Carmichael’s design for the Mona logo. It is a multiplication sign beside a plus sign, to signify the mathematician gambler. Or a cancellation mark beside a cross of crucifixion. Or a kiss before a sexual act that might generate an addition to the great chain of biological continuity. May many more of Mona’s books stream from magical Moorilla peninsula, once called Large Frying-pan Island, but let them focus more on the ideas in individual works of art. Monanisms and ‘Monanism’ stew the works into a bouillabaisse of David Walsh’s responses.

Monanism, the inaugural exhibition at the Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, 21 January–19 July 2011. The book Monanisms: Museum of Old and New Art is also available in luxury binding at $300 in a signed and numbered edition of 360 copies. See page 9 for more details.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.