Hedda Gabler | Belvoir St Theatre

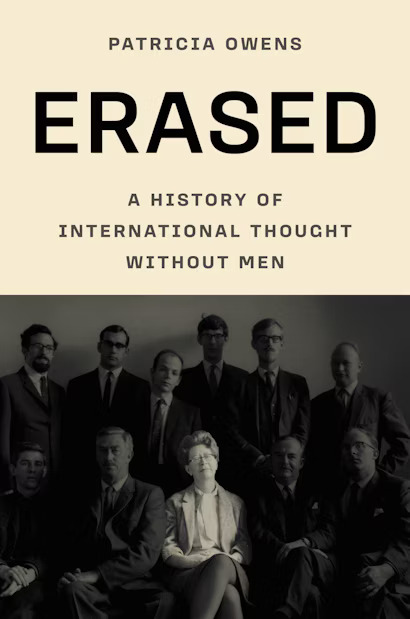

Hedda Gabler (1890) occupies a somewhat schizophrenic position in Henrik Ibsen’s work. On the one hand, it is normally seen as the apotheosis of Ibsen’s realist period, his sardonic homage to the fashionable ‘well-made play’ of the time. But, on the other hand, from early in its theatrical life there have been productions which have reacted against the naturalistic style in which the play seems to have been couched.

The Russian director Vslevold Meyerhold’s 1906 production had Hedda centrally enthroned while the rest of the cast struck poses and declaimed their lines in a monotone apparently so as to downplay the personal relationships and concentrate on Ibsen’s attack on bourgeois society. Ingmar Bergman’s iconic Swedish production, which electrified London audiences when Peter Daubeny imported it in one of his world theatre seasons in 1968 and which Bergman revived not so successfully for the National Theatre, concentrated on Hedda’s psyche. Bergman divided the stage with a centre panel, so that the audience saw not only the room in which the play is normally set but also the inner room to which Hedda retreats and throughout the play she could be seen pacing, staring at her reflection, and playing with her father’s pistols.

Henrik Ibsen (1906)

Henrik Ibsen (1906)

These two very different approaches highlight the central enigma of the play’s protagonist. Is Hedda simply a psychopath, a narcissist with a tendency towards melodrama, or is she a captive of her era, a woman of strength and intelligence whose fear of scandal has condemned her to a limited, meaningless existence and has warped her judgement?

Neither of these questions is answered or indeed even asked in the train wreck that calls itself Hedda Gabler at the Belvoir. In the original play, Hedda is a true product of her hidebound, nineteenth-century provincial society. The haute-bourgeois daughter of a general, married to Tesman, a dull, decent academic, she is fascinated by his unstable rival, Ejlert Lövborg, whom she romanticises into some sort of Dionysian figure with whom she never had the nerve to have an affair. She is willing to enter into a discreet ménage à trois with Judge Brack, but lacks the courage to do what the outwardly more conventional Thea Elvsted does and leave her husband. For some reason that, judging from her program notes, does not seem clear even to the director, Adena Jacobs, the play has been set in the present in a sort of dream America. This immediately negates the idea of a woman trapped by social convention. In nineteenth-century Europe, for an upper-class young woman to lose her virginity to a drunken reprobate, however romantic he might seem, would have been a dangerous step to take. In the present day, it would seem to be simply a rite of passage. Moreover, Ibsen contrasts Hedda’s cowardice with the courage of Thea Elvsted, who is willing to do what then would have been considered unthinkable and leave her husband to be with another man, something that is now an everyday occurance.

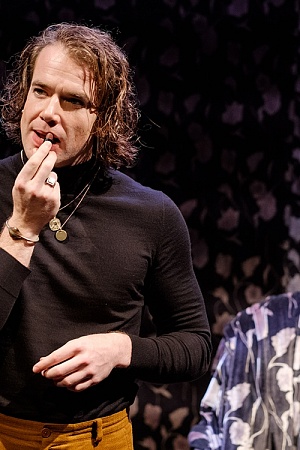

Marcus Graham as Brack and Ash Flanders as Hedda Gabler (photograph by Ellis Parrinder)

Marcus Graham as Brack and Ash Flanders as Hedda Gabler (photograph by Ellis Parrinder)

Having removed the social context in which the characters operate, one might think that Jacobs would have concentrated on the relationships between them. But the play has been so cut, or butchered, that we have the barest understanding of who these people are and how they interact. We lose Hedda’s edgy relationship with Tesman’s aunt Julie and her sarcastic put-downs of the servant Berte. Most of the banter between Hedda and Brack that clearly underlines their power play has gone. With the density of the play removed, what we are left with is a bunch of actors wandering onstage to give us the barest of plot points, which are punctuated by endless musical interludes. We are a long way from Ibsen – closer perhaps to performance art or some Zen nightmare.

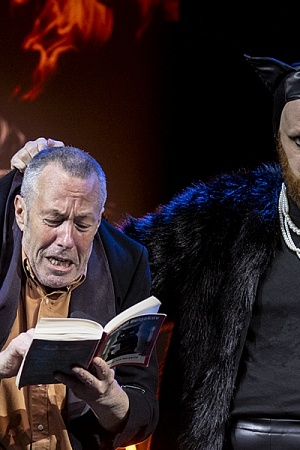

Given the circumstances, it may be unfair to comment on the actors, but here goes. The stalwarts, Lynette Curran as Julie and Marcus Graham as Brack, do their best to provide some sort of characterisation and momentum, but they end up defeated. Of the rest, Tim Walter’s Tesman hardly registers. As Lövborg, Oscar Redding drastically lacks the charisma central to the role. Anna Houston as Thea is an embarrassment, and Branden Christine as Berte skulks around to no great purpose.

Tim Walter as Tesman (photograph by Ellis Parrinder)

Tim Walter as Tesman (photograph by Ellis Parrinder)

And then there is Ash Flanders. There is no reason why a man should not play Hedda. One can imagine what the great Charles Ludlam must have made of the part when he played it in Pittsburg. His Camille, which I was lucky enough to witness, was an amazing blend of gender, camp, melodrama, and tragedy – artifice which led us to truth. Flanders’s whiny, one-note performance leads us nowhere and gives us no clue as to why he was cast.

How this disaster made it on to the main stage of the Belvoir is something that management need to consider.

Belvoir St Theatre’s production of Hedda Gabler, adapted by Adena Jacobs from the play by Henrik Ibsen, and directed by Adena Jacobs, runs until 3 August 2014 at Belvoir’s Upstairs Theatre. Performance attended 3 July.

Comments (2)

If you mean somewhat irreconcilable why not just say so? Sorry, I couldn't take the rest of the review seriously after the first sentence.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.