Stephen Ward Was Innocent, OK: The Case for Overturning his Conviction

Biteback Publishing (NewSouth), $24.99 hb, 207 pp, 9781849546904

Stephen Ward Was Innocent, OK: The Case for Overturning his Conviction by Geoffrey Robertson

Who was Stephen Ward? And why does his fate matter today?

The Profumo affair, with its mixture of sex, politics, aristocracy, and espionage, has become the archetypal scandal. In 1962, Jack Profumo was British Secretary of State for War (ministerial titles were more frank in those days). He had a brief affair with a beautiful young woman, Christine Keeler, who was introduced to him by Dr Stephen Ward, a society osteopath. There it might have ended but for the fact that she was also involved with a Soviet diplomat and spy, Yevgeny Ivanov. Efforts to cover up the affair were in vain, and Profumo resigned after admitting that he had lied to Parliament about the relationship.

Profumo spent the remaining decades of his life working humbly for a charity. He was drawn back into the embrace of the Establishment and made a Commander of the British Empire. For Dr Ward, ‘the ultimate victim of the Profumo affair’ (Advances, ABR, February 2014), there was no rehabilitation. He died by his own hand in 1963 on the eve of being convicted for ‘pimping’. As Geoffrey Robertson passionately argues in Stephen Ward Was Innocent, OK, the British Establishment conspired to destroy his reputation in a case which had no basis in fact. The purpose of this book, in fact, is to lay out the evidence for a review by the Criminal Cases Review Commission.

Christine Keeler in 1988

Christine Keeler in 1988

(photograph sourced)

The Conservative government of the time was badly embarrassed by the scandal and wanted a scapegoat on whom to divert attention and blame. There was also disquiet about the breakdown of sexual morality in 1960s Britain. Robertson delights in quoting Macaulay’s observation from 1831:

We know of no spectacle more so ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality ... We must take a stand against vice. We must teach libertines that the English people appreciate the importance of domestic ties … Our victim is ruined and heart-broken. And our virtue goes quietly to sleep for seven years more.

Ward was certainly an enthusiastic libertine, but one who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. That was sufficient to bring all the power the Establishment had at its command to destroy his reputation and good name. It is a chilling story.

Robertson makes his case with the precision and passion we have come to expect from him, forensically analysing and disproving all arguments until only his own is left standing. It is a beautiful thing to observe. Injustice usually occurs because of error or individual corruption, he writes. In the case of Ward, however, the entire prosecution of the case was corrupt, Robertson argues; it was a conspiracy of the government, police, and judiciary to intimidate and silence Ward. If this seems far-fetched, the reader is directed to appendices in which Robertson’s arguments are supported by a range of impressive legal authorities and commentators.

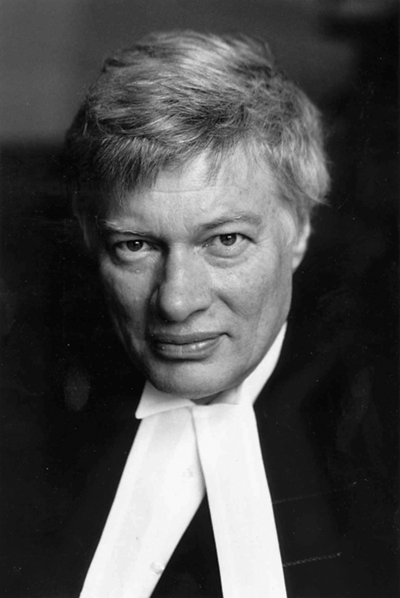

Geoffrey Robertson QC

Geoffrey Robertson QC

(photograph supplied)

Twelve distinct reasons are given for the conviction to go to appeal and be thrown out, each of which would be cause in itself. The home secretary of the time effectively instructed the police to ‘get Ward’. The charge of living off prostitutes’ earnings was absurd: the prosecution was only able to show that the well-to-do society doctor accepted a few pounds for use of the telephone while Keeler was staying at his apartment. The police hounded Ward, standing outside his consulting rooms and asking everyone who came out whether he had done anything inappropriate. His clientèle collapsed. A prostitute was bullied into lying that Ward was her pimp; otherwise the police threatened to take her child into care. In Parliament and the press, Ward was vilified as a depraved individual who deserved prison for his way of life alone. In the judge’s summing up, the jury was even invited to convict on the basis of moral judgement rather than any evidence before it: ‘You may think that the defendant is a thoroughly immoral man ... if you think that this is proved ... do your duty and return a verdict of guilty.’ By the time the verdict was handed down, Ward had already taken his own life in despair at his situation.

‘The Conservative government of the time was badly embarrassed by the scandal and wanted a scapegoat on whom to divert attention and blame.’

Geoffrey Robertson has done a service to Ward’s memory by assembling this case – the conviction is now being examined by the Criminal Cases Review Commission. This book also functions as a wider reminder of how public opinion and events can be manipulated by corrupt collusion between those in power, the media, and the police. The Leveson enquiry and recent trial of Rebekah Brooks have revealed a disturbingly intimate relationship between the media, the police, and senior government figures. It is instructive, too, to note how such appeals to morality continue to be used to exercise economic or political control, fifty years after the Profumo affair. In the past year, for example, the Metropolitan Police have begun regular raids on brothels in London’s famous Soho district, to ‘clean up’ the area. To suggest any connection with the property companies that own the area and have plans to redevelop it would, of course, be mere conspiracy theory.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.