Arts Highlights of the Year

To complement our popular ‘Books of the Year’ feature, to highlight ABR’s fast-expanding arts coverage, and to celebrate some excellent music, theatre, and film, we invited a group of critics and arts professionals to nominate some of their favourite productions of the year.

Robyn Archer

Dawn Upshaw’s concerts with the Australian Chamber Orchestra were staggeringly beautiful. Conceived with an elegant and intelligent touch, they featured the Australian première of Maria Schneider’s song cycle Winter Morning Walks. Dawn Upshaw’s subtly nuanced and warmly generous performance made Australia’s finest ensemble even finer in that moment. It’s not just the best for the year, but the best in decades.

Dawn Upshaw (photograph by Patrick Ryan)

Dawn Upshaw (photograph by Patrick Ryan)

From the accomplished to the emerging. Grace Clifford’s performance of the Beethoven Violin Concerto with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra made me understand that, while I love the skill of AFL footballers, I have to admit that, at this level, the arts win hands down. So young, so gifted, so much hard-won skill, and delivered with such humility and real grace.

My next selection is Crossing Roper Bar, at the Australian National Museum. I first saw this collaboration between the Australian Art Orchestra and Wagilak-speaking songmen of South East Arnhem Land in 2005. Nine years later it had evolved into a moving partnership between tradition and contemporary improvisation. Few performances could better express the rare essence of Australian optimism than this.

Ben Brooker

Ursula Mills and Tim Walter in Kryptonite (photograph by Lisa Tomasetti)

Ursula Mills and Tim Walter in Kryptonite (photograph by Lisa Tomasetti)

Toneelgroep’s Roman Tragedies was, for many, Adelaide’s theatrical event of the year. Unfolding over six hours on an expanded and immersive Festival Theatre stage, this cycle of Shakespeare’s unofficial trilogy of Roman plays stunned with its innovativeness, the quality of its performances, and the power and precision of its streamlined text.

Rarely performed as a complete cycle, Philip Glass’s ‘Portrait Trilogy’ of operas – Akhnaten, Einstein on the Beach, and Satyagraha (State Opera of South Australia) – was a landmark. Directed by Leigh Warren and designed by Mary Moore, each opera was given a more minimalist and choreographic rendering than is usual. As with Glass’s music, the overall effect was hypnotic.

Sue Smith’s two-hander, Kryptonite was a highlight of this year’s State Theatre Company of South Australia’s season. The play charts, from 1989 to the present day, the relationship between environmentalist turned politician Dylan and Lian, a Chinese-Australian who becomes a powerful businessperson. Fine performances by Tim Walter and Ursula Mills did justice to Smith’s punchy script, which provides a compelling metaphor for the Sino-Australian relationship in the Asian Century.

Tim Byrne

Three productions emerged as highlights this year, even if only one can lay claim to an entirely Australian genesis. It’s interesting to note that all of them featured outstanding performances by female actors, and all came from the independent scene. The first was George Brant’s one-woman play Grounded, from Red Stitch. A layered and lyric exploration of a female fighter pilot’s struggle with drone technology, it showcased the extraordinary talent of Kate Cole, who captured the vertiginous descent of her character with virtuosic assurance.

The second was Kin Collective’s trilogy of plays by Martin McDonagh, known collectively as The Leenane Trilogy. A massive undertaking, it managed to encompass an entire world view, and featured a bravura turn by Noni Hazlehurst, among others.

Maude Davey (Harry Crawford) and Caroline Lee (Annie Burkettby) in The Trouble with Harry (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Maude Davey (Harry Crawford) and Caroline Lee (Annie Burkettby) in The Trouble with Harry (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Finally, MKA produced the world première of Australian writer Lachlan Philpott’s stunning play The Trouble with Harry. It struck this reviewer as one of the finest plays this country has produced in years, and received a production to match. Performances were uniformly perfect, but special mention has to go to Maude Davey as the troubled Harry, and Caroline Lee as his tragically compromised wife.

Peter Craven

One of the finest performances I saw this year was Noni Hazlehurst’s as the mother in The Beauty Queen of Leenane, the revival of the whole of Martin McDonagh’s trilogy by the Kin Collective at fortyfivedownstairs was a highlight of the theatre calendar.

Robyn Nevin was also at the height of her powers as Ana in Neighbourhood Watch (Melbourne Theatre Company), and then there was the incomparable Miriam Margolyes in I’ll Eat You Last (Melbourne Theatre Company). Nadia Tass’s production of Annie Baker’s The Flick (which Red Stitch will revive in 2015) was a dazzling piece of work; all three lead actors, but especially Ngaire Dawn Fair, were staggeringly good.

Michala Banas, Noni Hazlehurst, Christopher Bunworth, Marg Downey, Mark Diaco, and James O’Connell in The Leenane trilogy (photograph by Lachlan Woods)

Michala Banas, Noni Hazlehurst, Christopher Bunworth, Marg Downey, Mark Diaco, and James O’Connell in The Leenane trilogy (photograph by Lachlan Woods)

Sigrid Thornton was a riveting Blanche du Bois in Black Swan’s production of A Street Car Named Desire, and Nicki Shiels’s performance as Helena in Bell Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream made one long to see her as Rosalind and Viola.

Brendan Cowell’s The Sublime (Melbourne Theatre Company) was a revelation.

Long-form television brought its high and mighty achievements, none better than – not the second series of The Bridge, nor The Fall – Devil’s Playground (Foxtel), which was superbly acted and scripted and had a compositional grandeur as well as a dazzling unpredictability.

Brendan Gleeson in Calvary

Brendan Gleeson in Calvary

In film, John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary deserved its high reputation, and both Stephen Knight’s Locke (with its tour de force performance from Tom Hardy) and Ruben Östlund’s Force Majeure were exceptional.

NT Live’s broadcast of David Hare’s Skylight showed that Carey Mulligan is already one of the world’s great actresses, and I don’t ever expect to see The Marriage of Figaro done better than in the Metropolitan Opera’s production by Richard Eyre, with James Levine conducting that most moody and wonderstruck of operas.

Ian Dickson

The year produced two excellent films in that most fraught of genres, the artist biopic. In Reaching for the Moon, Miranda Otto made a febrile, stubborn, ultimately ruthless Elizabeth Bishop in a film that managed to avoid most of the pitfalls of the category. Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner had Timothy Spall, a magnificent Turner, proving that he could get more mileage out of a grunt than most actors could from a two-page speech. But for me the film of the year was about a fictional artist, the failed actor, Aydin, the protagonist of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s majestic Winter Sleep.

A new work by Michael Gow is always an event, and Once in Royal David’s City (Belvoir) didn’t disappoint. The play was sensitively directed by Eamon Flack and superbly performed, especially by Brendan Cowell. Gow covered a wide range of themes. Death, the heartless inanity of late capitalist society, and the importance of art, especially theatre, in combattng this were viewed with Gow’s signature combination of rage and compassion.

Christine Goerke (Electra) in Elektra

Christine Goerke (Electra) in Elektra

David Robertson, the new musical director of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, is obviously not one to shy away from a challenge, and a semi-staged performance of Richard Strauss’s Elektra is certainly that. Christine Goerke’s astounding Electra, Lisa Gasteen’s deliciously creepy Clytemnestra, and Cheryl Barker’s lyrical Chrysothemis dominated the proceedings and allowed us to ignore the unnecessary dancers.

Andrew Fuhrmann

The stand-out theatre event in Melbourne this year was Red Stitch’s production of New York playwright Annie Baker’s The Flick. Directed by Nadia Tass, this was as good as anything the company has ever produced – a melancholic wonder.

Helen Morse as Anne in Dreamers (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Helen Morse as Anne in Dreamers (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Damien Ryan’s inspired adaptation of Henry V was the best thing I have seen from Bell Shakespeare since Lee Lewis’s Twelfth Night, while fortyfivedownstairs also had a strong year, highlighted by The Long Pigs, The Leenane Trilogy, and Daniel Keene’s Dreamers.

There were also a number of exciting, if ultimately frustrated, theatrical adventures worthy of mention: The Rabble’s Frankenstein, Peta Brady’s Ugly Mugs, and Chinese director Meng Jinghui’s anarchic Good Person of Szechuan, all at the Malthouse.

But none of it was as exciting as what we saw in the world of contemporary dance. The inaugural $30,000 Keir Choreographic Award created a huge buzz, with Atlanta Eke’s Body of Work a deserving winner. The scene has an inspiring energy at the moment, with so many young choreographers doing great work.

Then there was the Melbourne Festival’s comprehensive Trisha Brown retrospective, with the Trisha Brown Company presenting seventeen of the revolutionary choreographer’s works – a clear festival highlight.

Colin Golvan

The Australian Chamber Orchestra weekend at Tarrawarra Museum of Art is always a highlight of the concert year – an orchestra of great exuberance and finesse in a fabulous contemporary chamber setting.

The Melbourne Theatre Company production of Brendan Cowell’s The Sublime, a whoosh of a play set in the dark heartland of footballers and the sexual exploitation of young women.

Richard Linklater’s film Boyhood offered a serene piece of contemplation on family life and the passing of time.

Ellar Coltrane in Boyhood

Ellar Coltrane in Boyhood

Fiona Gruber

I really enjoyed seeing Patrick White’s pungent, gothic, and wonderfully wordy Night on Bald Mountain, a Malthouse Theatre production directed by Matthew Lutton, which marked the fiftieth anniversary of the play; Melita Jurisic as dipsomaniacal Miriam Sword, and Julie Forsyth as quaint Mrs Quodling with her goats, were particularly punchy.

Tilda Cobham-Hervey in 52 Tuesdays

Tilda Cobham-Hervey in 52 Tuesdays

I was very impressed by a film from Adelaide, 52 Tuesdays, directed by Sophie Hyde and starring the luminous Tilda Cobham-Hervey as a sixteen-year-old coming to terms with her mother’s gender reassignment and her own experiments in sex and socialising. It was witty, compassionate, and frank, and also a bold experiment in film-making

Third cab off the rank is Iain Grandage’s opera The Riders based on Tim Winton’s novel of the same name but with considerable liberties taken in the plot. In this powerful piece of musical writing and characterisation, Barry Ryan put in a fine performance as Winton’s innocent abroad, Scully. The Victorian Opera production in September was effective but a bit sparse. It would be nice to see it again with a bigger budget, unlikely though this is.

Alastair Jackson

Stuart Skelton (Otello) and Jonathan Summers (Iago) star in Otello (photograph by Alistair Muir)

Stuart Skelton (Otello) and Jonathan Summers (Iago) star in Otello (photograph by Alistair Muir)

To mark the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, English National Opera mounted a new production of Verdi’s Otello in September. Director David Alden changed the normally black-faced Moor into an assimilated Muslim-turned-Christian who led the Venetian forces against the Turks circa 1920s. Australian tenor Stuart Skelton, who had previously worked with Alden as Peter Grimes, was singing Otello for the first time and succeeded admirably in bringing the character to life. Desdemona was the rising American lyric soprano Leah Crocetto, making her UK début, and veteran Australian baritone Jonathan Summers was in fine form as the sinister Iago. Edward Gardner conducted superbly, and the audience responded accordingly.

Verdi’s Il Trovatore requires four great voices, and Teatro La Fenice had them in their October revival of Lorenzo Mariani’s production from 2011. Carmen Giannattasio, who had just completed an enormously successful season as Maria Stuarda at Covent Garden, was a magnificent Leonora. Sought-after American tenor Gregory Kunde sang Manrico, and Artur Rucinski, a true Verdi baritone, was a very convincing Count di Luna. Veronica Simeoni sang well as Azucena, but was not sufficiently dramatic. It didn’t help that she looked more like Manrico’s daughter than his mother. The highlight of the evening was the brilliant young Italian conductor Daniele Rustioni, a protégé of Antonio Papano, who almost stole the show in a masterly example of Verdian conducting.

Opera Australia opened its Melbourne Spring Season with splendid new production of Puccini’s Tosca. John Bell’s clever updating to Mussolini’s Italy worked well and brought out the inherent drama better than most other Toscas we have seen in Australia. The beautifully mounted production will serve the company well. Any changes are cogent and, like Tosca’s rather unorthodox exit in Act III, relevant to the time and place of the setting. Austrian soprano Martina Serafin was perfect as Tosca, both vocally and dramatically. She was ably supported by Mexican tenor Diego Torre as Cavaradossi, and Italian barirone Claudio Sgura was a suitably menacing Scarpia. Conductor Andrea Molina brought out a wonderful reading of the score by Orchestra Victoria.

Mary Lou Jelbart

There is an inexplicable attraction in a marathon cultural event, the urge to saturate body and mind in Wagner’s Ring or Peter Brook’s Mahabharata – or in my case, fourteen continuous hours of Schubert (the 3MBS 2014 fundraiser at ANAM). The heat and the uncomfortable were irrelevant as forty-five of our finest musicians played impromptus, song cycles, trios, quartets, and the pinnacle – the String Quintet, Schubert’s masterwork, composed just before his death. It was music-making of great beauty and poignancy.

Derek Ives in The Long Pigs

Derek Ives in The Long Pigs

The Trouble with Harry, by Lachlan Philpott at Northcote Town Hall, overcame the difficult aural environment of the venue by equipping each audience member with headphones, and actors with head mikes. It was a device that worked brilliantly, making the tragic (true) story of ‘Harry’ extraordinarily intimate. Maude Davey gave one of the outstanding performances of the year as the transgender ‘Harry’. This was theatre-making of apparent simplicity but great skill, beautifully directed by Alyson Campbell.

Conflict of interest declaration! Clare Bartholomew, Derek Ives, and Nicci Wilks are the clowns of nightmares, and their disturbing, murderous, blasphemous, and cannibalistic clowns were a sensation in The Long Pigs (fortyfivedownstairs). Bartholomew was a merciless and controlling bully; Ives the hapless, crucified figure; and Wilks the indomitable miniature creature surviving against the odds. I was not the only one captivated by this strange, undefinable work, directed by Susie Dee, which has now been invited to numerous festivals here and overseas.

Valerie Lawson

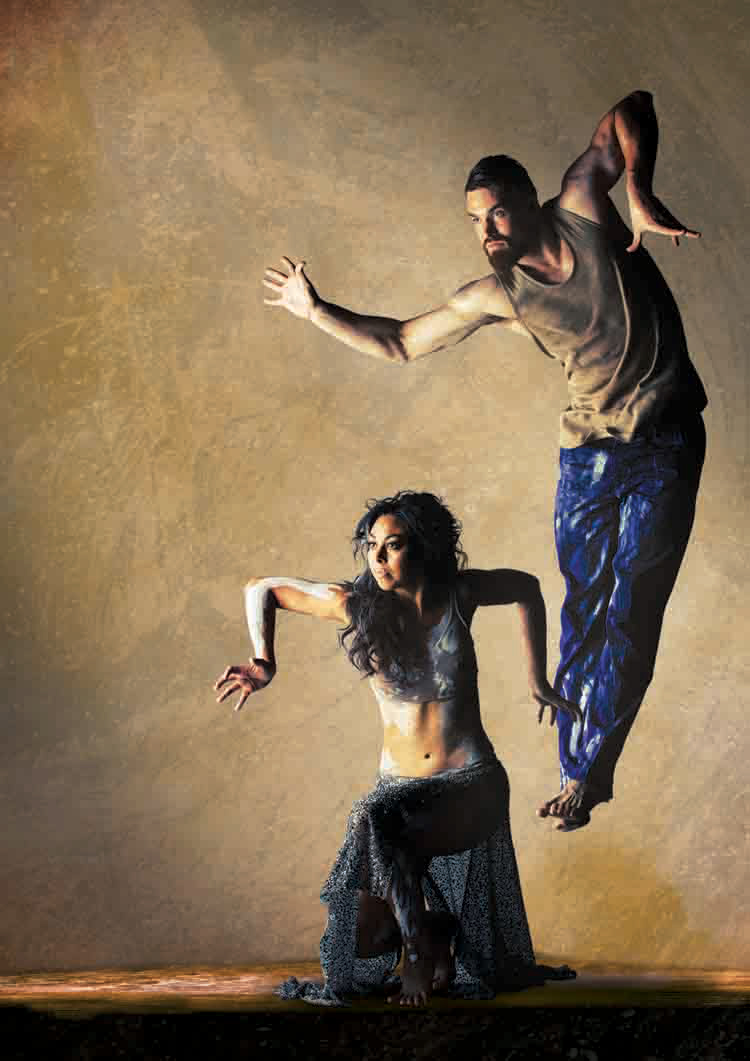

Bangarra Dance Theatre's Patyegarang

Bangarra Dance Theatre's Patyegarang

It’s been the year of the guest artist, with both the Australian Ballet and Queensland Ballet adding the sparkle (and box office draw card) of some outstanding artists. Highlights included the Australian Ballet’s guests: Gillian Murphy, a principal with American Ballet Theatre, dancing in La Bayadère, and Alina Cojocaru (English National Ballet) with Johan Kobborg (formerly a principal with the Royal Ballet) in Manon.

Tamara Rojo (English National Ballet) was exceptional in the Queensland Ballet’s production of Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet. The company’s performance marked the first time MacMillan’s 1965 production was staged in Australia.

For the interesting range of principal dancers and their outstanding artistry, the most impressive visiting company was American Ballet Theatre. The company’s triple bill Bach Partita, Seven Sonatas, and Fancy Free was the highlight of ABT’s Brisbane season.

Bangarra Dance Theatre celebrated its quarter century with Patyegarang, a visually stunning new work by the company’s artistic director, Stephen Page.

Wayne McGregor’s Chroma entered and enlivened the Australian Ballet’s repertoire.

Dancing at the Australian Dance Awards gala in Sydney, Kristina Chan once again demonstrated her artistry in her solo work, Crestfallen.

Brian McFarlane

In a provocative year for Australian films were two conspicuously tough-minded pieces. After Animal Kingdom’s critical success in 2010, expectations for director David Michôd’s new film, The Rover, were high, and were convincingly met. It works as a gripping thriller, but is more than that: it is a riveting study of two minds coming to terms with each other; is interested in the workings and repercussions of violence; and makes most unsettling use of Australian landscape.

Guy Pearce and Robert Pattinson in The Rover

Guy Pearce and Robert Pattinson in The Rover

In Tony Mahony and Angus Sampson’s The Mule, much of the action is confined to a bleak motel where the naïve young eponym is watched over by a pair of brutal detectives waiting for him to excrete drugs ingested in Thailand. Not a pretty idea, but powerful stuff depicting an ugly trade for the vile thing it is. The US film of the year is Gone Girl (Boyhood offered stiff competition), again holding interest throughout as a thriller but its real substance lying elsewhere. Director David Fincher and screenwriter Gillian Flynn (adapting her own novel) have compelled attention to the dynamics of a marital mismatching, to the persuasively workmanlike police search for the girl (‘gone’ in several ways), and to the often-obstructive behaviour of the media.

Michael Morley

Behzod Abduraimov

Behzod Abduraimov

I am doubtless not the only viewer who thought that Richard Linklater, the director of Boyhood, had found some magical way of compressing time – from the film’s almost three hours’ running running time to what felt like barely ninety minutes. Shot over twelve years, with the same actors ageing in accordance with the film’s (fictional) storyline, Boyhood plays like a series of Chekhovian episodes covering days and years in the lives and confusions of a generation of characters. As one critic observed, the film-maker and his cast found a way of presenting scenes that follow the rhythm of life. Haunting, funny, and worth watching not twice, but three or four times.

There were two standout musical performances this year in Adelaide: the return of the remarkable young Tashkenti pianist Behzod Abduraimov, whose fresh-minted, non-hyperbolic account of that warhorse known as Rach Three (Adelaide Symphony Orchestra) managed to persuade most listeners that it is a far better piece than it usually sounds; and the sixteen-year-old Young Performer of the Year, Grace Clifford, whose performance of the Beethoven Violin Concerto was not just spectacular for its technical accuracy and poise, but also for the maturity and vitality of her interpretation. She is clearly a star in the making.

Peter Rose

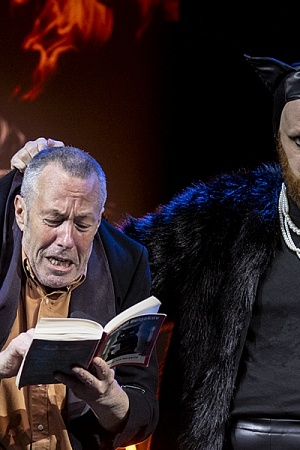

Maria Mercedes is Maria Callas in Master Class (photograph courtesy of fortyfivedownstairs)

Maria Mercedes is Maria Callas in Master Class (photograph courtesy of fortyfivedownstairs)

In opera, it was hard not to be stirred by Jonathan Kent’s new Manon Lescaut at Covent Garden, with Jonas Kaufmann in mighty voice not long before his sensational concerts for Opera Australia – a commanding singer at the height of his powers. Best of the local fare was David McVicar’s new production of Don Giovanni for Opera Australia, which brought perspective and gravitas to the tiny Sydney stage, and highlighted a prodigious Australian talent, Nicole Car.

Melbourne saw consummate performances from Maria Mercedes as Maria Callas in Terence McNally’s Master Class (fortyfivedownstairs) and Miriam Margoyles as Sue Mengers in John Logan’s I’ll East You Last (MTC). McNally’s 1993 study in divadom is better than Logan’s biographical play (should we really be guffawing about the skulls of Cambodia in 2014?). Maria Mercedes was unforgettable as Callas, and I am sure she will be again next September, when she reprises the role.

I loved two emphatically different films, Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, which brought a Nouvelle Vague insouciance to Rome; and Pantelis Voulgaris’s Little England, a beautifully acted family melodrama which rightly opened the Greek Film Festival.

Dina Ross

Lee Mason and Christopher Bunworth in East

Lee Mason and Christopher Bunworth in East

Both my choices are ensemble productions with casts of six or more, and they bookend a year in theatre. Black Water Theatre Company’s production of Steven Berkoff’s East was a stand-out, with director Peta Hanrahan milking every scene for physical comedy and brash, in-your-face irreverence. In November, the Keene-Taylor Theatre Project reunited after a long hiatus with Daniel Keene’s melancholic Dreamers. This play, which tackled racism, ageism, and idealism with poetic flair, suffered from an abrupt and unsatisfactory ending, but still demonstrated what can be achieved when superlative writing, acting, and directing combine to create magic on stage.

Eloise Ross

Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin is an adaptation of Michel Faber’s novel of the same name, written in 2000, and incorporates some of the mysterious and sinister science fiction elements from its source material. Scarlett Johansson’s performance as an alien-like creature, partly improvised, is at once isolating and wholly involving. The films wraps its strikingly dark visual palette in a chilling soundscape and an intriguing experimental score by Mica Levi.

Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston in Only Lovers Left Alive

Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston in Only Lovers Left Alive

Ari Folman’s The Congress is an ambitious mixture of live-action and animation that warily imagines a future of film production without actors. Robin Wright stars as a parallel version of herself who eventually submits to having her body and all its expressions digitised for the film studio’s archive. Adapted from Stanisław Lem’s novel The Futurological Congress (1971), the film is visually spectacular, embracing the widescreen format and revelling in the possibilities of the cinema.

Only Lovers Left Alive is a vampire film steeped in director Jim Jarmusch’s particular brand of laconic cool. Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston, both embracing their androgynous sensuality, are centuries-old soul mates, separated and then reunited in Detroit and Tangiers. It features a script filled with sharp literary allusions, and an irresistible soundtrack, including music from Jarmusch’s band SQÜRL.

The Iranian film A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (Ana Lily Amirpour) shares influences with Jarmusch and will be a valuable entry to the realm of vampiric fiction.

Mary Vallentine

The title The Eradication of Schizophrenia in Western Lapland by Ridiculusmus sounds more like a lecture than a play. Created by David Woods and Jon Haynes, this ambitious, funny, and moving piece consists of two plays, with the same characters performed simultaneously. Two audience groups sit opposite each with two acting spaces dividing them. We could hear bits of the other play, which were texturally woven with our play. Several characters moved between the two. The effect was a polyphonic soundscape portraying a world where auditory hallucination was the norm. By entering this world, we empathised and engaged. Open Dialogue, an early intervention treatment program for schizophrenia, has eradicated the disease in Finnish western Lapland in the twenty years since it began. Open Dialogues treats uncertainty and polyphonic voices as normal. While clearly informing this theatrical realisation, it is the plays’ effect on the audience that presents the most compelling case for compassion and for advocating the adoption of this treatment.

PLEXUS – comprised of Monica Curro (violin), Phillip Arkinstall ( clarinet), and Stefan Cassomenos (piano) – performs music commissioned from Australian composers. So far they have given twenty-two premières, with another twenty or so slated for next year. Their first concert had us on the edge of our seats as we experienced the excitement of hearing six premières. The ‘sandwich’ principle of a short, obligatory new Oz comp wedged between two standard repertoire pieces did not apply here. These champions of the new engaged us in their adventure and it was thrilling. Fortyfivedownstairs, the Salon at Melbourne Recital Centre, and Port Fairy Festival have each hosted concerts by PLEXUS since its formation this year.

Jordi Savall’s Jerusalem is not Australian. It was too great and humane an experience to ignore, however. The music inspired by this city across different faiths was overwhelming. We all left Melbourne Recital Centre convinced – at least for that one night – that peace in the Middle East was achievable.

Jake Wilson

The Babadook

The Babadook

In a better-than-average year for Australian cinema, Rolf de Heer made his best film in Charlie’s Country, an enraged but unsentimental parable about the ruin of indigenous cultures, with David Gulpilil – who deserves the label ‘national treasure’ if anyone does – in a role that amounts to his King Lear.

The other local standout was Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook, a textbook demonstration of the most frequently overlooked principle of horror film-making: a director who can make us believe her characters are real people will be able to deliver infinitely more effective scares.

For those who were able to attend the Melbourne International Film Festival, the cinematic event of the year was the second-ever Australian screening of Out 1 (1971) Jacques Rivette’s legendary improvised serial about theatre, conspiracy, and mental illness, conceived as a sinister scavenger hunt or a chess game with Paris as the board. Running for nearly thirteen hours, this puts most subsequent examples of long-form moving-image storytelling in the shade.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.