The Némirovsky Question: The life, death and legacy of a Jewish writer in 20th century France

Yale University Press (Footprint), $53.99 hb, 364 pp, 9780300171969

The Némirovsky Question: The life, death and legacy of a Jewish writer in 20th century France by Susan Rubin Suleiman

When Irène Némirovsky’s Suite Française appeared in 2004, it was a huge success, in France and throughout the English-speaking world as well. Its account of France’s collapse at the beginning of World War II, and its portrayal of the early part of the German Occupation, are now acknowledged as profoundly insightful and of an epic scope matched by few other writers. In addition, the story of the quasi-miraculous survival of the uncompleted manuscript, purportedly kept for fifty years in a suitcase by the daughter of the author who had perished in Auschwitz, provided an almost mythical aura to the Némirovsky phenomenon.

The enthusiasm generated by what appeared to be the discovery of a ‘new’ major author was soon to be tempered by other revelations. Némirovsky, between the wars, had been not just a recognised novelist, but a commercially successful and critically fêted star. The problems were that many of the author’s closest literary associates were later tarnished by collaborationist activities or tendencies, and that much of her work, including her most famous novel, David Golder (1929), was intensely critical of Jews and Jewishness. This provoked a still-heated debate about whether Némirovsky – a Russian Jewish immigrant in France, and a Shoah victim – was anti-Semitic, a Jew-hating Jew.

Nobody could be more qualified to bring balanced understanding to this debate than Susan Rubin Suleiman. Harvard professor, and author of many books on topics including women’s writing, the place of ideology in fiction, issues concerned with Jewishness (including her own), and the literature, politics, and memory of World War II in France, Suleiman harnesses all her expertise and experience to reflect on what she calls the ‘Némirovsky question’. This is an authoritative work, beautifully written, though not without its moments of uncertainty.

For the Némirovsky question, far from being a single one, turns out to be a multitude of interlocking enigmas, puzzles, and complexities, few of which make for easy resolution. Some of them have to do with the many paradoxes in Némirovsky’s own character: for example, the fearlessness and skill with which, as a foreign woman in France’s snobbish and male-dominated literary field, she built her career as a writer – as against the apparent blindness and passivity with which she failed to secure her own and her family’s safety when the need to do so had become obvious. Why did she not apply earlier for French citizenship? Was her 1939 conversion to Catholicism merely a tardy attempt to escape discrimination, or was she genuinely seeking a greater sense of spiritual belonging? How could she have declared her admiration for Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s first and most violent anti-Semitic tract, Bagatelles pour un massacre (1937)? Did she really think that a personal appeal to Pétain to exempt her and her family from Vichy’s anti-Jewish laws could succeed? Suleiman does not provide definitive answers to such questions, but she examines them with the patience and rigour characteristic of the best scholarship.

Another strand of investigation illuminates the social and political history of France in the 1920s and 1930s, when the rise of totalitarianism in both the east and the west drove hundreds of thousands into France to seek refuge, reigniting traditional anti-Semitism, and provoking a broader surge in xenophobic and racist sentiment, not least among the well-to-do and established French Jewish community. How this situation evolved into France’s shameful and willing wartime deportation of so many of its Jews to the Nazi death camps is documented and analysed with lucidity, but also in a way that suggests disturbing analogies between the forces at work in Némirovsky’s world and those confronting present-day readers.

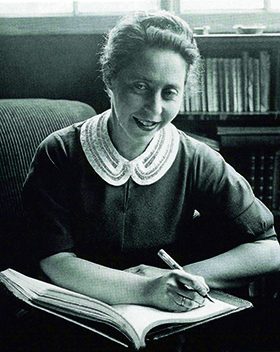

Irène Némirovsky and her parents and maternal grandparents, 1922 (Némirovsky papers, IMEC archive)

Irène Némirovsky and her parents and maternal grandparents, 1922 (Némirovsky papers, IMEC archive)

Pulsing beneath these individual and socio-political dimensions is the deepest question of all for Suleiman, that of Jewish identity and destiny. Through Némirovsky, Suleiman probes at the experience of Jewishness as race, culture, and religion, proposing the disquieting view that no Jew can ever really cease to be a foreigner or a stranger in the country where he or she chooses to live: ingrained anxiety and fear from the long experience of persecution and ongoing discrimination, exponentially sharpened by the horrors of the Shoah, have become inescapable and unerasable facts of Jewish life. Is this indeed the case? As a non-Jewish reader, I do not feel competent to judge; but I do not doubt the authenticity of Suleiman’s testimony.

Irène Némirovsky, 1938 (photograph by Roger-Viollet, the Roger-Violett Archive)While neither a biography nor a literary study in itself, The Némirovsky Question contains enough about Némirovsky’s life and work to provide a sound introduction for those who do not yet know her. There are also many useful clarifications and corrections to commonly held misapprehensions, including the intriguing but false story of the manuscript in the suitcase. Like her character Ada in Les chiens et les loups (1940, translation The Dogs and the Wolves, 2009), Némirovsky searched endlessly for ‘the secrets hidden beneath sad faces and dark skies’, and this search, as Suleiman shows, produced a body of work that, whatever its problematic aspects, has enduring literary merit. But Suleiman’s most compelling contribution is her positioning of Némirovsky as an emblematic figure in the context of much of the last century of French cultural life. The personal trajectory of the female writer – famed, forgotten, rediscovered; her tragic fate as a foreign Jew; her legacy as the mother of two daughters who both became writers and founded families that now appear to be successfully integrated into the tapestry of contemporary French society: these themes are developed against the background of a France that struggled unsuccessfully to rebuild itself after World War I, and tried to bury the shame and guilt of its official collaborationism in World War II by excising the Vichy period from its history. With impressive erudition, Suleiman demonstrates that the re-emergence of Némirovsky as a writer to be reckoned with is integral to the process by which the French – novelists and historians first, then more slowly the politicians, educators, and public – have finally begun to come to more truthful terms with their past.

Irène Némirovsky, 1938 (photograph by Roger-Viollet, the Roger-Violett Archive)While neither a biography nor a literary study in itself, The Némirovsky Question contains enough about Némirovsky’s life and work to provide a sound introduction for those who do not yet know her. There are also many useful clarifications and corrections to commonly held misapprehensions, including the intriguing but false story of the manuscript in the suitcase. Like her character Ada in Les chiens et les loups (1940, translation The Dogs and the Wolves, 2009), Némirovsky searched endlessly for ‘the secrets hidden beneath sad faces and dark skies’, and this search, as Suleiman shows, produced a body of work that, whatever its problematic aspects, has enduring literary merit. But Suleiman’s most compelling contribution is her positioning of Némirovsky as an emblematic figure in the context of much of the last century of French cultural life. The personal trajectory of the female writer – famed, forgotten, rediscovered; her tragic fate as a foreign Jew; her legacy as the mother of two daughters who both became writers and founded families that now appear to be successfully integrated into the tapestry of contemporary French society: these themes are developed against the background of a France that struggled unsuccessfully to rebuild itself after World War I, and tried to bury the shame and guilt of its official collaborationism in World War II by excising the Vichy period from its history. With impressive erudition, Suleiman demonstrates that the re-emergence of Némirovsky as a writer to be reckoned with is integral to the process by which the French – novelists and historians first, then more slowly the politicians, educators, and public – have finally begun to come to more truthful terms with their past.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.