The Vandemonian War: The secret history of Britain’s Tasmanian invasion

Hardie Grant Books, $29.99 pb, 422 pp, 9781743793114

The Vandemonian War: The secret history of Britain’s Tasmanian invasion by Nick Brodie

Nick Brodie, a medievalist and ‘professional history nerd’, enjoys writing in a revelatory tone. His latest book, The Vandemonian War: The secret history of Britain’s Tasmanian invasion, claims to unveil ‘for the first time’ the ‘real story’ of the Tasmanian conflict in the 1820s and 1830s known as the Black War or the Vandemonian War. It is an argument against the generations of historians who have ‘failed to see through the myths and lies’ about Tasmania’s intensely militarised past. These nameless individuals, he contends, neglected crucial documents about the invasion – ‘even when they knew of them’. The real Vandemonian War remained hidden, Brodie argues – ‘until now’.

The basis for Brodie’s claim is his ‘discovery’ of the inbound and outbound correspondence from the Colonial Secretary’s Office in the Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office in Hobart, designated CSO1/1/320 and CSO41/1/1 (7578). Brodie seems to be unaware of Tasmanian Aboriginal curator Julie Gough’s ongoing project to transcribe the ‘7578’ files and to publish them online; he brushes over the extensive study of part of the ‘7578’ archive offered by N.J.B. Plomley in Friendly Mission (1966); and he declines to engage with the work of the ‘tiny fraction’ of historians who have breathed meaning and insight into this archive over recent decades. Indeed, he dispenses with this rich vein of scholarship in his first two footnotes and does not refer to the work of a single contemporary scholar in the text. Instead, he embarks on a fine-grained discussion of the primary source material: the troop orders, mission reports, and arms catalogues that ‘capture history as it happened’.

The Vandemonian War certainly brings a wealth of rich material on frontier violence into the public domain, yet it will be difficult for most readers to discern what is new here, as Brodie claims that everything he has uncovered is new. ‘Everyone will be shocked,’ he warns at the start of his grand exposition: ‘Whole societies were deliberately obliterated. And genocide, I have come to realise, can be a starched white-collar crime.’

The book provides a detailed account of the military logistics in Tasmania between 1828 and 1832. Brodie’s characters are administrators, militiamen, paramilitary parties, regimental soldiers, mercenaries, brigadiers, commanders, sergeants, corporates, privates, special forces, and ‘Aboriginal auxiliaries’. He translates the conflict into the language of war, describing the various tactical strategies, pincer movements, and intelligence operations undertaken by the British. He even playfully opens one chapter with the line, ‘All was relatively quiet on the western front in early winter 1830.’ This embrace of the genre of military history underlines his core argument about the Vandemonian War: the conflict was industrial and intensely militaristic, but has been ‘de-militarised’ in popular memory ‘in favour of a narrative focused on sporadic skirmishes’.

The relentless blow-by-blow description of the individual campaigns is successful in conveying the systematic attempts by the British military and paramilitary to ‘harass Aboriginal people into surrender or degrade them into annihilation’. And the fact that Brodie hews so close to his sources will make the book a valuable resource to other scholars seeking easy access to this fragile archive. The sources provide a fascinating window on the transitory world of the frontier, and they are sometimes enriched by a discussion of the layered nature of the archive. In January 1830, for example, Richard Tyrrell reported an encounter with two Aboriginal people roasting kangaroo by their fires near the highland lakes. Suspecting others would be nearby, Tyrrell felt ‘reluctantly obliged to fire at the Two’. The Colonial Secretary later underlined this phrase, writing a single word in the margin of the report: ‘why?’ It is a revealing glimpse of puzzlement.

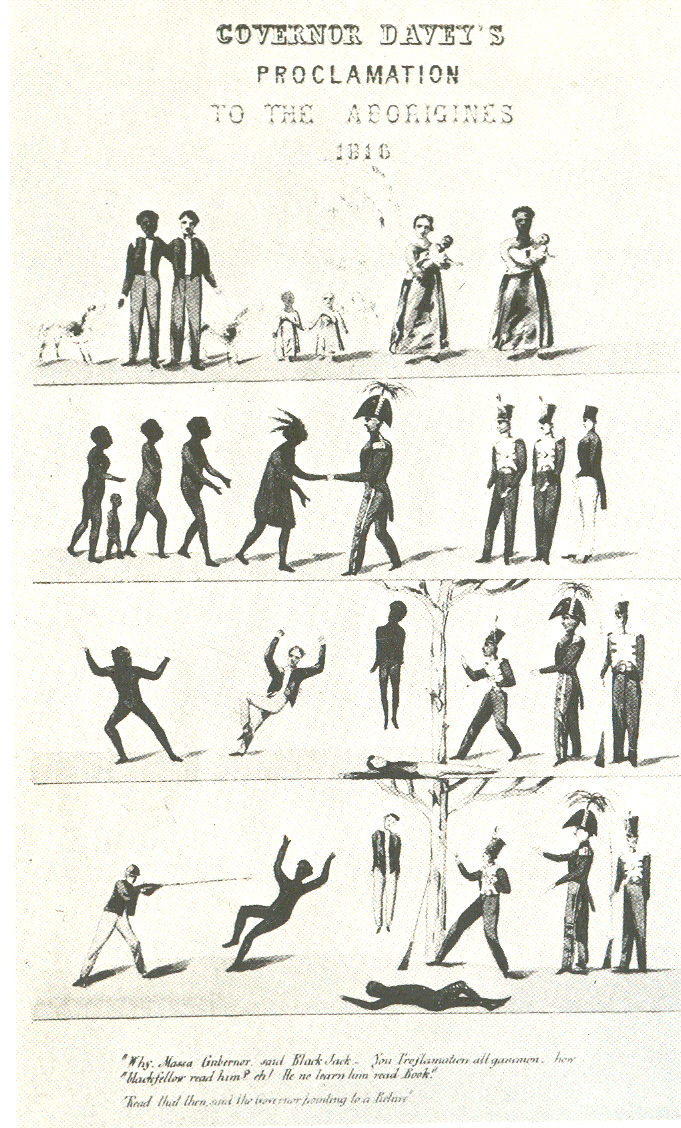

A lithographic reproduction of 'Governor Davey's Proclamation to the Aborigines' (Wikimedia Commons)But the question of ‘why?’ remains unanswered in The Vandemonian War. Brodie gives little consideration to the intent behind the repeated missions, aside from broad statements about conquest and genocide. What was the purpose of the policy of ‘conciliation’? Was it simply, as he suggests, another word for ‘ethnic cleansing’? What of the humanitarian rhetoric, even genuine concern, expressed by colonial leaders? This is where some dialogue with other scholars – such as Lyndall Ryan, Henry Reynolds, James Boyce, Nicholas Clements, Fae Dussart, Murray Johnson, Tom Lawson, Alan Lester, Ian McFarlane, and Rebe Taylor – would have strengthened the analysis.

A lithographic reproduction of 'Governor Davey's Proclamation to the Aborigines' (Wikimedia Commons)But the question of ‘why?’ remains unanswered in The Vandemonian War. Brodie gives little consideration to the intent behind the repeated missions, aside from broad statements about conquest and genocide. What was the purpose of the policy of ‘conciliation’? Was it simply, as he suggests, another word for ‘ethnic cleansing’? What of the humanitarian rhetoric, even genuine concern, expressed by colonial leaders? This is where some dialogue with other scholars – such as Lyndall Ryan, Henry Reynolds, James Boyce, Nicholas Clements, Fae Dussart, Murray Johnson, Tom Lawson, Alan Lester, Ian McFarlane, and Rebe Taylor – would have strengthened the analysis.

There is also remarkably little space given to the Aboriginal people against whom this war was waged. What strategies did Aboriginal people employ to resist the ‘mass military mobilisation’? Brodie struggles to move beyond the documentary record, instead lamenting that ‘The surviving Aboriginal people of Van Diemen’s Land mostly died in exile and the Vandemonian War disappeared from public memory with them.’ Nevertheless, he claims credit for highlighting the ‘complex spectrum of inter-cultural interactions that has been too often overlooked in Vandemonian history’, adding, tautologically, ‘But cultural exchanges often went two ways.’

If framed differently, The Vandemonian War might have become another important contribution to the so-called ‘history wars’, for it makes a strong case for the Tasmanian frontier to be viewed through the lens of formal warfare. Yet Brodie only makes a single veiled reference to the charged debate, and in doing so he groups both sides together, dismissing it as a fight over ‘different versions of the same lie’. It is only now, he asserts, that the ‘lie’ of sporadic skirmishes has been vanquished: the Vandemonian War was more warlike, more orchestrated, and more horrific than anyone ever thought or believed – until Brodie wrote this breathless military history.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.