News from the Editor's Desk - January-February 2018

Forty not out

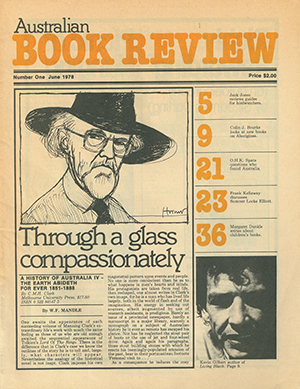

With this double issue, Australian Book Review enters its fortieth year. ABR was of course founded in Adelaide in 1961 as a monthly magazine. Max Harris and Rosemary Wighton edited the first series, whose final, quarterly appearances lapsed in 1974. The second series was created in 1978 under the auspices of the National Book Council. Edited by John McLaren (1978–86), ABR had moved to Melbourne – first Carlton, then Richmond, now soaring Southbank. The April issue will mark the four-hundredth appearance of the magazine in its second guise.

First issue, June 1978Forty years is a substantial run for any publication, and it seems fitting for a magazine undergoing immense change to reflect on the achievements, sacrifices, and intentions of those original editors and their supporters. ABR, in a sometimes difficult market for little magazines, has survived and adapted to new modes, new literary movements, new technologies because of the commitment of hundreds of individuals – and more than 3,100 contributors. None was more selfless or tenacious than my predecessor, Helen Daniel, who edited ABR from 1995 until her death in late 2000.

First issue, June 1978Forty years is a substantial run for any publication, and it seems fitting for a magazine undergoing immense change to reflect on the achievements, sacrifices, and intentions of those original editors and their supporters. ABR, in a sometimes difficult market for little magazines, has survived and adapted to new modes, new literary movements, new technologies because of the commitment of hundreds of individuals – and more than 3,100 contributors. None was more selfless or tenacious than my predecessor, Helen Daniel, who edited ABR from 1995 until her death in late 2000.

To celebrate their achievements and mark this new, ambitious chapter in the magazine’s life, we will unveil new programs and features throughout the year. In February we will name the ABR Fortieth Birthday Fellow (we thank all those who have applied). The following month we will announce a new development that will be of considerable interest to our many contributors. Several themed issues will follow. Major public events will take place here and overseas, including one at the Australian Embassy in Berlin during our German tour in June.

Four decades is a milestone, but to myself and my colleagues – given the magazine’s present robustness and potential – it feels as though we are just starting out. Ed.

Jolley Prize

Advances was entertained by online reactions to Kristen Roupenian’s short story ‘Cat Person’, which triggered a flurry of ‘hot takes’, tweets, and commentary after it appeared in The New Yorker on December 11 and went viral online. Responses ranged from befuddlement to outrage. Some people, convinced that it was an essay rather than a story, questioned its fictional bona fides. But it was gratifying to see short fiction generating so much attention.

The ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize, one of the world’s premier awards for an original short story, has always welcomed new styles and voices. We look forward to being inspirited by new exponents of the genre with the opening of the 2018 Jolley Prize. The Jolley is worth a total of $12,500, of which the overall winner will receive $7,000. The runner-up receives $2,000, the third-placed author $1,000. Three commended stories will share the remaining $2,500. This year the judges are Patrick Allington, Michelle Cahill, and Beejay Silcox.

The three shortlisted stories will appear in our August 2018 issue; and the three commended stories will appear later. The overall winner will be announced at a ceremony in August. As with our other literary prizes, the Jolley Prize is open to writers anywhere in the world (stories must be in English). It is easy to enter, simply visit our website for more details. The Terms and Conditions are detailed and comprehensive; and we have also updated our Frequently Asked Questions. (It’s amazing what people ask!) Writers have until 10 April to enter.

The Jolley Prize is funded by ABR Patron Ian Dickson. We thank him warmly.

Richard Flanagan

Fake news it seemed at first – or a mistimed April Fool’s Day spoof. Writing in The Australian on 11 December, Stephen Romei (the literary editor) reported that ‘Richard Flanagan has decided to boycott the Miles Franklin Literary Award ... a response fuelled by bitter personal disappointment’.

Flanagan, as we know, has been shortlisted on five occasions but has never won the Award. The most recent nomination was in 2014 for The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which had previously won the Man Booker Prize. According to another admirer quoted in Romei’s article, Geordie Williamson, this was ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back, as I understand it’.

Richard Flanagan’s withdrawal seems unfortunate, and it is to be hoped he will reconsider in comings years. Flanagan has had much patronage from readers, government, and universities. He has won several literary prizes, including the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for fiction in 2014, when – in a widely criticised intervention – Prime Minister Tony Abbott overturned the judges’ decision and insisted on The Narrow Road to the Deep North’s sharing the prize with Steven Carroll’s A World of Other People.

Remarkably, Flanagan is quoted as predicting in a September 2017 interview with Romei that he would never win the Miles Franklin Literary Award. ‘I won’t win ever. I’m confident that I won’t win.’ Such negative ‘confidence’ seems extraordinary and misplaced. Is there a suggestion here that the Miles Franklin Literary Award per se or successive judging panels have been ill-disposed towards Richard Flanagan? Why would this be? Because of Flanagan’s politics, his prominence, his Guildhall triumph, his Tasmanianness ...? The Miles jury changes regularly. No one serving on it now was there in 1995, when Flanagan was first shortlisted. (Disclosure: I was a judge from 1997 to 2001.)

Flanagan’s ‘boycott’ seems ungenerous to four of the novels that prevailed in the years when he was shortlisted: Tim Winton’s Dirt Music (2002), Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria (2007), Tim Winton’s Breath (2009), and Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing (2014). (Advances will draw a heavy curtain over the first shortlisting, when the Miles went to Helen Demidenko for The Hand That Signed the Paper, the most freakish and regrettable decision in the long history of the Award.)

Many writers would draw solace or incentive from a quintet of shortlistings for Australia’s premier literary award.

Richard Flanagan

Richard Flanagan

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, admired by many, was not without its critics. Michael Hofmann and Craig Raine were mordant about the novel in the LRB and TLS, respectively. Our critic, James Ley, was more positive in his review in the October 2013 issue, yet he remarked on ‘peculiar lapses of judgement’ and ‘a tendency to overplay his hand, to end his chapters with a flourish ...’ (Ley reviewed First Person in our November 2017 issue and considered it ‘Flanagan’s most artfully constructed and thematically complex novel to date’.) Literary judgement, like any prize jury, is ultimately subjective – not a ratification of celebrity or multiple shortlistings.

There is also a strong whiff of cultural cringe about this brouhaha. Just because an Australian novel wins the Man Booker Prize doesn’t mean that local judges should roll over in agreement. Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang – surely one of the greatest modern Australian novels – won the Booker Prize in 2001 but not the Miles Franklin Literary Award, for which it was shortlisted. It happens.

Australia probably has more literary prizes than there are days in the year. In a difficult environment for creative writers, they supplement incomes, boost morale, and in some cases increase sales. But prizes can have a toxic effect on our literary culture, skewing reputations and warping expectations.

To our knowledge, Richard Flanagan has not commented publicly on this ‘boycott’. ABR invited his publisher, Penguin Random House, to do so, but received no reply. Ed.

Porter Prize

When submissions closed four weeks ago, we had received just under 1,000 entries in the Peter Porter Poetry Prize, our biggest field to date. We know what our three judges – John Hawke, Bill Manhire, and Jen Webb – will be reading over summer.

The five shortlisted poems will appear in our March issue. The winner will then be named at a free public ceremony at fortyfivedownstairs in Melbourne on Monday, 19 March. Following readings from the work of Peter Porter, the five poets will read their poems, after which a distinguished guest will announce the overall winner.

Alexis Wright and the Boisbouvier Chair

Alexis Wright (photograph by Vincent Long)

Alexis Wright (photograph by Vincent Long)

Alexis Wright, award-winning novelist and member of the Waanyi nation of the Gulf of Carpentaria, has been appointed as the Boisbouvier Chair in Australian Literature at the University of Melbourne. The Boisbouvier Chair in Australian Literature was established in 2015 thanks to a $5 million gift from John Wylie and Myriam Boisbouvier-Wylie. Richard Flanagan was the inaugural chair in 2015.

‘I hope that I can do some justice to the position by sharing my experience, knowledge, and vision as a practising writer of over thirty years,’ said Wright. Her new book is Tracker: Stories of Tracker Tilmouth. Michael Winkler reviews it in this issue.

Marten Bequest

The Marten Bequest Scholarships – begun in 1979 – are one of the great travel scholarships offered in Australia. Administered by the Australia Council for the Arts, the Marten Bequest is offering travelling scholarships for Australian artists and writers to explore, study, and develop their artistic practices through interstate or overseas travel. The Marten Bequest Scholarship offers $50,000, paid in quarterly instalments over two years, to Australian-born artists between the ages of 21-35. Applications close 31 January 2018.

Comment (1)

I have to confess that I have never read anything of Richard Flanagan but I am amazed to learn that he persisted so long to try to win the Miles Franklin Literary Award. Anything in excess of three attempts would seem to me to be dishonouring for an author of his calibre and reputation.

His writing was not perfect ? He had shortcomings, you say ? He had ‘peculiar lapses of judgement’ and ‘a tendency to overplay his hand, to end his chapters with a flourish ... Whereas, each award winner, without exception, all these years ... ?

As you say, Peter: "literary judgement, like any prize jury, is ultimately subjective", and, might I add: "completely relative".

The fact that he achieved the extraordinary feat of being shortlisted five times by five different, independent juries is, one may consider, just as meritorious as being judged the best candidate on just one occasion by a single jury.

Allow me to suggest that the members of those five different, independent juries should, perhaps, be asked to consider according him the award, exceptionally, for the high standard of the total body of his work, and for having persisted so dauntlessly and so relentlessly for long.

.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.