Yellow Notebook: Diaries, Volume I, 1978–1987

Text Publishing, $29.99 hb, 253 pp, 9781922268143

Yellow Notebook: Diaries, Volume I, 1978–1987 by Helen Garner

‘Several new perceptions of the unfortunate creature that I am have dawned upon me consolingly.’

Franz Kafka, 7 January 1911

Anyone who keeps a diary day in, day out for decades knows why Helen Garner, a few years ago, destroyed her early ones, deeming them boring and self-obsessed. Incineration has a long, proud history: think of Henry James, late in life, at his incinerator in Rye, burning all his letters and private papers – that lamentable blaze. The sheer misery and tedium of our early journals can be dejecting. ‘What is the point of this diary?’ Garner asks herself in 1981. ‘There is always something deeper, that I don’t write, even when I think I’m saying everything.’

Few of us know why we keep diaries, and few of us actually consult them, but nor can we imagine how people (especially writers) manage to get through life without them. What do they do with their mornings, their midnights? According to Cynthia Ozick, ‘Journal entries, those vessels of discontent, are notoriously fickle.’ But they can also be antidotes for boredom, panic, heartbreak, slights – those esprits de l’escalier. Harry Kessler, one of the greatest of diarists, wrote on 18 September 1888: ‘When I am alone like this evening it often strikes me what an infinitely small proportion my outer life … bears to my inner life, the life I live with myself; hardly the spray that is thrown off the ocean by the wind.’

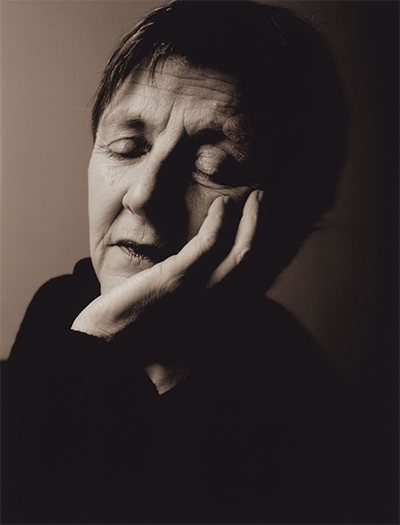

Helen Garner, 2004, by Julian Kingma. Collection National Portrait Gallery.

Helen Garner, 2004, by Julian Kingma. Collection National Portrait Gallery.

Of the life ‘lived with herself’, Garner has been diarising ‘for almost all of her life’, we are told on the jacket of this new compilation of diary entries from 1978 to 1987 – her first, but assuredly not her last (Volume I, the jacket proclaims). While retaining the years, Garner has excised the dismal dates that can give journals such a leaden quality, the chronicling of the quotidian being such a ‘poor method of self-preservation’ (Nabokov).

While a few acquaintances are named (Frank Moorhouse, Elizabeth Jolley, Raymond Carver), most of the players, especially the intimates, are reduced to initials. At the beginning, Garner is in Paris. Monkey Grip behind her, she is trying to write screenplays and fiction. She has met F, the Frenchman who will become her second husband and then leave her for one of her sisters. Already there is a certain fractiousness: they quarrel when Garner won’t show F a fan letter she has written to Woody Allen. By 1986 she writes, ‘No wonder he can’t stand me. I can hardly stand myself.’

Much later, there is L, ‘an unfairly handsome man who was at the festival’. (The adverb is as choice as a good-looking man.) By 1987 she must choose between L and V, the writer who will become her third husband. When V tells her in a letter that he wants to see her, ‘a gong of terror’ sounds in the bottom of her stomach. ‘Something chilling in him. His intellect.’ He praises her handwriting (‘nicely childlike, and yet not’), and her response is characteristic: ‘Why would anyone so brilliant … want to have anything to do with me?’

The men in this book (some famous, some not) are vivid yet somehow extraneous. They seem like Garner’s straight men, or bent men (incidental, malleable as a draft) as she works out how much she needs them, how much they need her. Trust doesn’t seem to come into it. In 1986 she writes, ‘I see that what I am doing, in this diary, is conducting an argument with myself, about these two men, and myself, and men in general.’

Nathaniel Hawthorne once described his wife as the ‘Queen of Journalisers’ on being shown her Cuban diary. What sobriquets will Garner’s ex-husbands and lovers deploy on reading this volume?

Throughout, there is a pedal note of self-loathing. The eleventh entry reads, ‘I have a lot of trouble with self-disgust.’ Later, Garner ‘crashes’ into ‘appalling bouts of self-doubt, revulsion at my past behaviour, loathing for my emotional habits’. She carries around ‘an inventory of my crimes. Everyone else is busy with their own.’ The note of violence throughout is pointed: ‘I need to find out why I so often get myself into situations where people have to symbolically murder me.’ (Kafka: ‘This morning, for the first time in a long time, the joy again of imagining a knife twisted in my heart.’)

Garner has often spoken of her abiding sense of rage. We’ve heard her do so at literary festivals and independent bookshops, those most pacific settings. She reminds us at times of Sylvia Plath – her fury at the world, her indignation at a renegade husband. Elizabeth Hardwick, in her peerless essay on the American poet, writes: ‘The sense of betrayal, even of hatred, did not leave her weak and complaining so much as determined and ambitious. Ambitious rage is all over Ariel.’

It also vivifies these diaries.

What we don’t find here are many literary insights into other writers. Seldom does Garner dwell on technical matters. Jane Austen, we learn, never describes the appearance of her characters; D.H. Lawrence ‘uses the same word over and over again till he makes it mean what he needs it to’; Elizabeth Bowen is ‘very good of course in an infuriating English way’ – but that’s about all.

Garner’s real subject is her own dogged, uncertain progress as a writer. The diary, though often self-flagellatory, is a spur to industry and acclamation. Like an athlete she goads herself, wills herself – full of doubt (‘My mind is full of stories but I lack the nerve to catch one and try to pin it down’) but always ambitious, unswerving. She frets about negative reviews. When she is shortlisted for a premier’s award, she ‘wants that prize’. Upon winning a festival award, she trembles at the knees.

Not for nothing does she choose this epigraph from Primo Levi: ‘We are here for this – to make mistakes and to correct ourselves, to stand the blows and hand them out.’ To an unusual degree, Garner the diarist is vividly and ineluctably present.

Casual eclecticism characterises the best diarists. We think of Thomas Mann: ‘Brief evening walk in a silk suit, downstream among the bats, which I am afraid of’; or this from William Gerhardie: ‘Played tennis in the afternoon; then had a woman; then a bath, and afterwards witnessed a revolution.’ Rarely does Garner skip a minor epiphany. Always she is noticing, practising, flexing her immaculate prose (‘My problems are never syntactic’):

In the shack I get up to take the kettle off the fire and see through the narrow window a pretty sight: a blue wren flirting with his own reflection in the outside mirror of my car. He flips up, whirring his wings like mad, performs a caracole and a pirouette in mid-air before the glass, then perches on the mirror’s rim and looks around in confusion – then back he goes and does it all again.

By now we know many things about Helen Garner, or think we do. We have been reading her novels and stories and journalism for more than forty years, and she has supplemented these with regular self-commentary. Non-fiction works like The First Stone (1995) and Joe Cinque’s Consolation (2004) have reinforced her reputation as a ceaseless judge of others and herself (‘I am very much a moralist,’ she writes in 1986). What these diaries do is restore our sense of what a superb comic writer she is: ‘I called P in Paris, and heard $29.30 worth of information about her vaginal infection.’ Then there is the young male photographer who exhorts her to smile (‘Big smile. Love those big smiles’):

‘Please don’t tell me to smile.’

‘You look starched.’

‘I am starched. I am a starched person.’

Starched or not – severe, unbending, falling about at the absurdity of the world – Helen Garner emerges as a moralist rippling with intent and mirth. The diary, clearly, is her true métier. And now we have successive volumes to anticipate. The titular promise and confidence are typical of this brilliant, defiant book.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.