Season of reckoning

What do we call this terrifying summer? The special bushfire edition of ABC’s Four Corners predictably called it Black Summer. Perhaps the name will stick, for it builds on a vernacular tradition. Firestorms are always given names, generally after the day of the week they struck. There are enough ‘Black’ days in modern Australian history to fill up a week several times over – Black Sundays, Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays – and a Red Tuesday too, plus the grim irony of an Ash Wednesday. The blackness of the day evokes mourning and grief, the funereal silence of the forests after a firestorm. Black and still. And when the fires burn for months, a single Black Day morphs into a Black Summer.

But does this name truly capture what is new about this season? The recent fires have left a black legacy, but the terrifying thing about them was that they were relentlessly red. Red and restless. The colour of danger, of ever-lurking flame. Acrid orange smoke and pyrocumuli of peril. The threat was always there; it was never over until the season itself turned. The enduring image is of people cowering on beaches in a red-orange glow. It was the Red Summer.

In early January, in an essay for Inside Story, I called it Savage Summer; I was writing while the fires were still burning and there was no sign of a black day-after. Stephen J. Pyne, a great wordsmith of fire, reached for another alliteration, calling them the Forever Fires. That name signals the change Pyne perceives in fire behaviour, from occasional visitations to total engulfment, which is the predicament of the Pyrocene, a new Fire Age comparable to past Ice Ages. His term ‘Forever Fires’ also reminds us, as James Bradley did in the Guardian, that ‘this is not the new normal. This is just the beginning.’ The future will be worse than this, much worse, unless we swiftly address the cause.

Whether we call the summer black, red, or savage, we shouldn’t forget that the fires started in winter. Even the season was ruptured. Where can language go once a whole summer is declared black and the fires are forever? What will we call the next eruption of fire? Will the black days that fused in a red summer become nameless, seamless years of inferno?

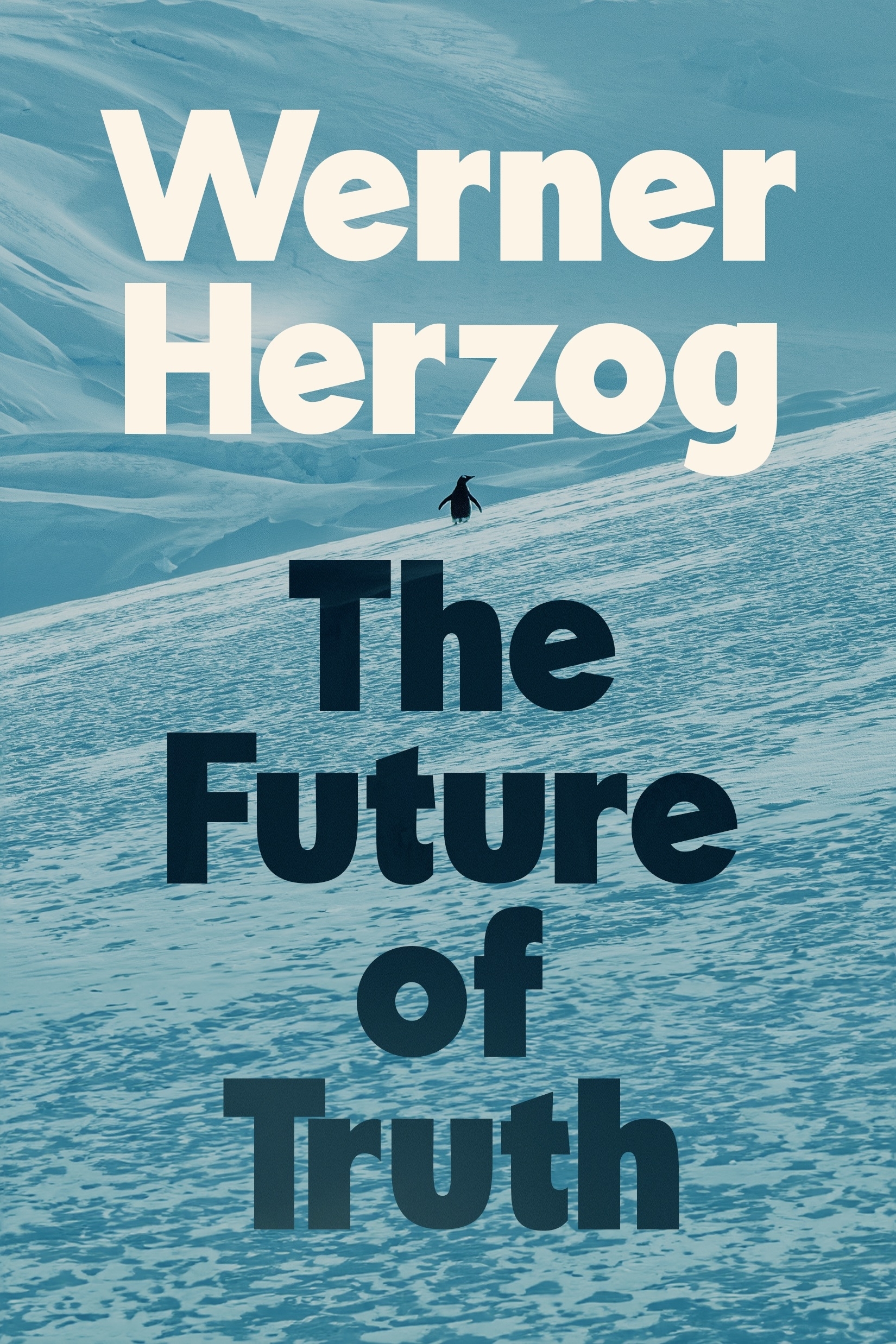

Gospers Mountain bushfire. NSW, 2019 (photograph by Nick Moir)

Gospers Mountain bushfire. NSW, 2019 (photograph by Nick Moir)

There is something personal about fire, something frighteningly irrational and ultimately beyond our comprehension. It roars out of the bush, out of our nightmares. Not only do we give the great fires names, we also assign them the characteristics of monsters: they have flanks, fingers, and tongues; they’re hungry; they know where we are; they lick and they devour. In reports of the fires of 1919, 1926, and 1939, houses were ‘swallowed’ and people were ‘caught between the jaws of the flame’. Fire ‘with its appetite whetted … sought more victims, and fiercely attacked’, and ‘with each change of wind … made a thrust towards the township, threatening to lick up the scattered homes on the fringe’. Bushfire makes its victims feel hunted down and its survivors toyed with. Why did the fire destroy the house next door and leave mine unscathed? A Black Saturday survivor who lost his home confessed, ‘I felt as if the fire knew me.’ A book about the 2003 Canberra fires took as its title a child’s question: How did the fire know we lived here?

Fire is the genie of the bush ready to escape, ‘the red steer’ jumping the fence and running amok, the rampant beast that can savage and kill. Instead of the sprites, elves and wood nymphs that populated the forest folklore of the Northern Hemisphere, Australian colonists found that their bush harboured a rather different creature. As poet Les Murray put it, the ‘gum forest’s smoky ambience reminds us that the presiding spirit who sleeps at its unreachable heart is not troll or goblin, but an orange-yellow monster who forbids any lasting intrusion there’. People on the New South Wales south coast referred to the Currowan fire, which rampaged for seventy-four days, as ‘the beast’.

During this searing summer, we have seen the best and worst of Australia: the instinctive strength of bush communities and the manipulative malevolence of fossil-fuelled politicians. The clash between the two – symbolised by a prime minister forcing handshakes on survivors – added to the trauma of the fires. As we watched our political establishment double down on denial, we were forced to realise that even the shock of this season may not change our national politics.

Where does this Australian intransigence come from? It is embedded so deeply in our history that we can hardly identify it. It comes from a conquest mentality that was built on denial, the denial of Aboriginal sovereignty and cultural sophistication. It comes from a frontier mining history and an economic dependence on coal. And it comes from enduring puzzlement about the nature of Australia, a nature that British settlers slowly learned was prone to climatic extremes that were natural rather than aberrant. Dealing with the traumas of flood, drought, and fire, and learning to expect and fight them, was part of becoming Australian. Many farmers and bush folk have been slow to accept climate change because they have spent their lives coming to terms with extreme natural variability. Their rural experience makes them sceptical about a different variability, especially when it is global, one-way, and unnatural. It’s like the rules of the game have suddenly changed. Thus, the history of modern Australian settlement sedated the populace against recognising its greatest peril.

But there are signs of hope in the exponential growth of quality Australian writing about fire. Black Friday 1939 produced one outstanding literary statement: Judge Stretton’s powerful and poetic Royal Commission report that was included in anthologies of nature writing and became a prescribed text for Matriculation English. Ash Wednesday 1983 found its greatest literary expression in Pyne’s Burning Bush (1991), which was written in its long afterglow. Black Saturday 2009 produced a crop of fine writing, impressive in its range and cultural depth, notably Adrian Hyland’s Kinglake-350, Karen Kissane’s Worst of Days, Robert Kenny’s Gardens of Fire, Peter Stanley’s Black Saturday at Steels Creek, Chloe Hooper’s The Arsonist, and Peg Fraser’s Black Saturday: Not the end of the story.

This savage summer has already germinated a very different forest of literary reflections. Writing sprouted immediately from active firegrounds, and it described something that was neither an ‘event’ nor just ‘Australian’: it was a planetary phenomenon. Fire is no longer a local or national story. Australia is the canary in the coal-mine, a belated warning of planetary peril. The world is watching us. We are the burning frontier of a warming world, the perilous cliff-edge of the Sixth Extinction. This may be the first fire season that Australians have tried to calculate the mortality of wildlife.

Fire was not just more extensive, intense, and enduring; it went rogue. Australia burnt from the end of winter to the end of summer, from Queensland to Western Australia, from Kangaroo Island to Tasmania, from the Adelaide Hills to East Gippsland, in the Great Western Woodlands and up and down the eastern seaboard. The season did indeed represent something new or ‘unprecedented’, to use the word avoided by denialists, who used history lazily to deny that anything extraordinary was happening. But our long history of bushfire is significant precisely because it makes us the prime site for a global eruption. Bushfire is integral to Australian ecology, culture, and identity; it is scripted into the deep biological and human history of a land of drought and flooding rains. But reciting Dorothea Mackellar does not forestall heeding Ross Garnaut. They are not in tension, for one amplifies the other. Of all developed nations, the sunburnt country is the most vulnerable to climate change because of her history of ‘flood and fire and famine’ and the chemistry of ‘her beauty and her terror’.

In a searing piece of reportage from the New South Wales south coast for The Monthly, Bronwyn Adcock was witness to ‘Australians doing everything they could, even when their government didn’t’. If the fires revealed the strength of bush communities and the innate goodness of people in extremis, so too did they reveal the absence of federal leadership and the weakness of our parliamentary democracy. As if neglect and omission were not enough, coalition politicians hastily encouraged lies about the causes of the fires, declaring that they were started by arsonists and that greenies prevented hazard-reduction burns. Yet we know that these fires were overwhelmingly started by dry lightning in remote terrain and that hazard-reduction burning – which is far from a panacea – is constrained by a warming climate. The effort to stymie sensible policy reform after the fires has been as pernicious as the failure to plan in advance of them.

The recent fires delivered a liminal moment for the nation, landing us on the beach of a fearsome planetary future. There can be no evacuation. Whatever we call this summer, will we make it a season of reckoning?

Comment (1)

But to imply that such fires might become the new normal, or last forever (Griffiths, ABR, March 2020) is to ignore ecology and miss the most terrifying threat they pose.

The more frequent, more severe, and longer-lasting fires we are seeing under a changed climate will inevitably exhaust the natural regenerative capacity of our native ecosystems. Over time, the forests will disappear, accelerating reduced rainfall and falling water tables, and leading to the aridification and desertification of previously habitable areas.

Fires may be the least of our worries when there is nothing left to burn.

Danielle Clode,

Author of A Future in Flames

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.