Thinking in headlines

What we read at difficult times in our lives – plague, insurrection, divorce, major root canal work, etc. – is always telling. Carlyle, miserable and unwell at Kirkcaldy, read the whole of Gibbon straight through – twelve volumes in twelve days – with a kind of horrified fascination. I recall one friend who, at a time of ineffable tension, calmly read Les Misérables, one thousand pages long, in a single week. (I would have been incapable of reading a tabloid.) Another time, lovelorn in Siena, I stayed in my ghastly hotel room and read The Aunt’s Story right through while the handsome Sienese sunned themselves in the companionable Campo.

We’ve all been interested in what people are reading at this [fill in the space] time. Are we seeking consolation, insight, succour, or comic distraction? Kirsten Tranter, writing from highly covidic California, notes in a review to be published in ABR’s October issue: ‘There is something about lockdown and its strange effects on the mind that makes every text seem like a code for the situation of quarantine.’

After my autumn of existentialism – essential after the jolts of March – I have begun to look elsewhere, though my habit of starting the day with a new poem by Wallace Stevens, in chronological order, continues – a necessary fillip. As I write this, I am up to The Auroras of Autumn, only eight years to go (remarkable ones though). Much though I want 2020 to end, I don’t think I want to reach ‘Not Ideas About the Thing But the Thing Itself’ – the final poem in The Rock. Will it coincide with the Last Lockdown or with confirmation that there will be no vaccine, no relaxation, no midnight unmasking?

Stevens aside, after a volley of books about the egregious Trump – several of which will be reviewed next month – I turned to Frank Kermode’s 1995 memoir, Not Entitled – merely dipped into before, I’m not sure why, for I have read most of Kermode’s other books, in some cases more than once, for the phrasing, the perspicacity, the poise.

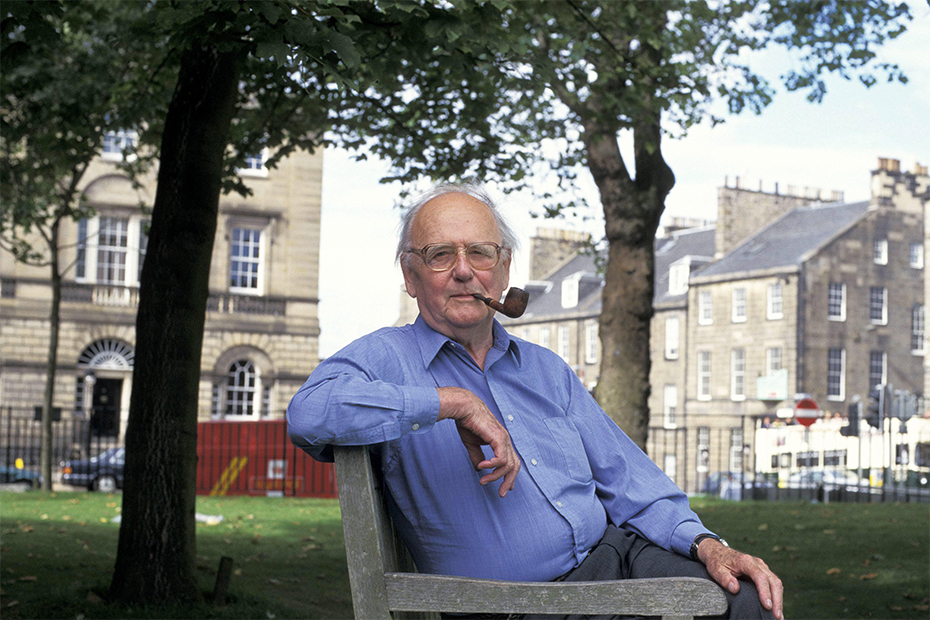

Frank Kermode, 2000 (photograph by Basso Cannarsa/Agence Opale/Alamy)

Frank Kermode, 2000 (photograph by Basso Cannarsa/Agence Opale/Alamy)

I met Kermode once. This was in 1988. He was in Australia for a sojourn at the legendary Humanities Research Centre in Canberra, presided over by his great friend Ian Donaldson. Afterwards he came to Melbourne. I recall the day well. A fire at the Footscray Tyre Works had clouded the city in toxic smoke. The Melbourne General Cemetery looked even more gothic than usual.

That evening, Peter Craven and Michael Heyward hosted a reception for Kermode at Scripsi ’s home, Ormond College. I was working for Oxford University Press at the time – a minnow in marketing. OUP had just published History and Value, a collection of Kermode’s Clarendon Lectures and Northcliffe Lectures. At Ormond, Kermode lectured on Horace, Marvell, and Auden. I met him briefly at the reception afterwards (memorable for its Scripsian prodigality of wine). I had a keen sense of how much he’d read and how much I hadn’t. Kermode was genial, interested, unpompous – a surprise after some of the Oxonians who dropped in at Normanby Road, some of whom fell asleep at meetings, whether from jetlag or boredom. (Kermode, a Manxman, went to Liverpool, not Oxbridge.) He enjoined me to read the London Review of Books, which he had instigated in 1979.

Not everyone relished Not Entitled. I remember that Ian Donaldson was troubled by his old colleague’s almost reflexive pessimism and self-disgust – the endless sense of doom running through this short memoir of his childhood on the Isle of Man (forever setting him part), his bizarre experiences in the British Navy during the war, and his subsequent departmental reversals in the academy.

Kermode is always lucid and clear-eyed about life, war included. Here he is towards the end of the riveting chapter on his naval service, the follies of war, his randy colleagues, and all his mad captains. He is conscious of

the petrifaction of sensibility war imposes: an observation that may not be fully intelligible to anybody who did not experience the war, even if it could be claimed that peace as we have subsequently known it has its own petrifying power. In wartime people are actively prevented from thinking except in headlines, many of them lies. Simple personal freedoms are sacrificed, and the mind volunteers for, or is conscripted into, banality.

Inevitably, I thought of the pandemic (ceaseless subject): how it makes us think in headlines, some of them lies. (Kermode again: ‘So there is in journalism an unavoidable tendency to error, as there is in navigational dead reckoning.’) Worse still are the platitudes, the repetitions, the nightly jeremiads on the news. (How many times can we speculate about what Covid clings to without going mad?) At times, as in a farce, we all seem to dart through the same door, think the same way. How convenient for government if this proves true. Those of us who worry about the new zeal of authority – in an already concessive and conformist age – wonder what will emerge from this era of threat, fiat, compulsion. Is satire possible at such a time? What personal freedoms are being sacrificed along the way? Will we miss them? What banalities must the mind endure? Will we go on thinking in headlines, muttering into our metaphorical masks?

Or will a new kind of thinking emerge to disrupt our glum orthodoxies – a movement, a visionary, dare I say it a resistance, impatient with prohibition, submission, and petrifying power?

This article, one of a series of ABR commentaries addressing cultural and political subjects, was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments (3)

Something of a coming-of-age moment as much as a difficult one, as it was the first genuinely thrilling text I had read and understood, while simultaneously coming to terms with the normally benign Tasmania turning on some extreme weather.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.