Review

The Third Force: Angau’s New Guinea War 1942-46 by Alan Powell

by Hugh Dillon •

The Default Country: A lexical cartography of twentieth-century Australia by J.M. Arthur

by Kate Burridge •

History on the Couch: Essays in History and Psychoanalysis edited by Joy Damousi and Robert Reynolds

by Dolly MacKinnon •

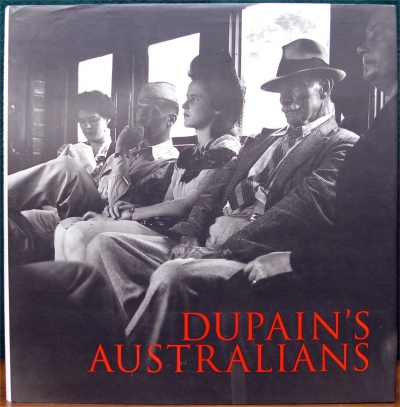

Dupain’s Australians by Jill White (text by Frank Moorhouse)

by Isobel Crombie •

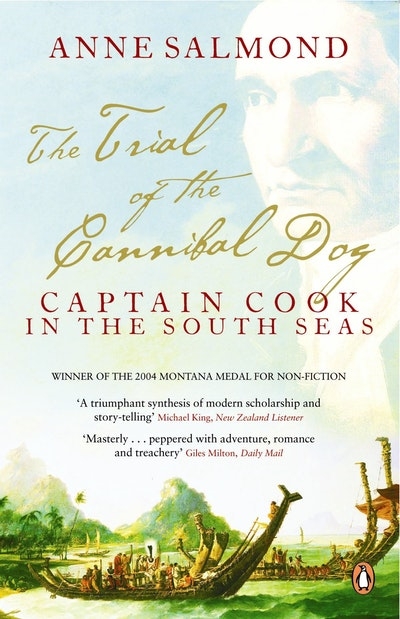

The Trial of the Cannibal Dog: Captain Cook in the South Seas by Anne Salmond

by Alan Frost •