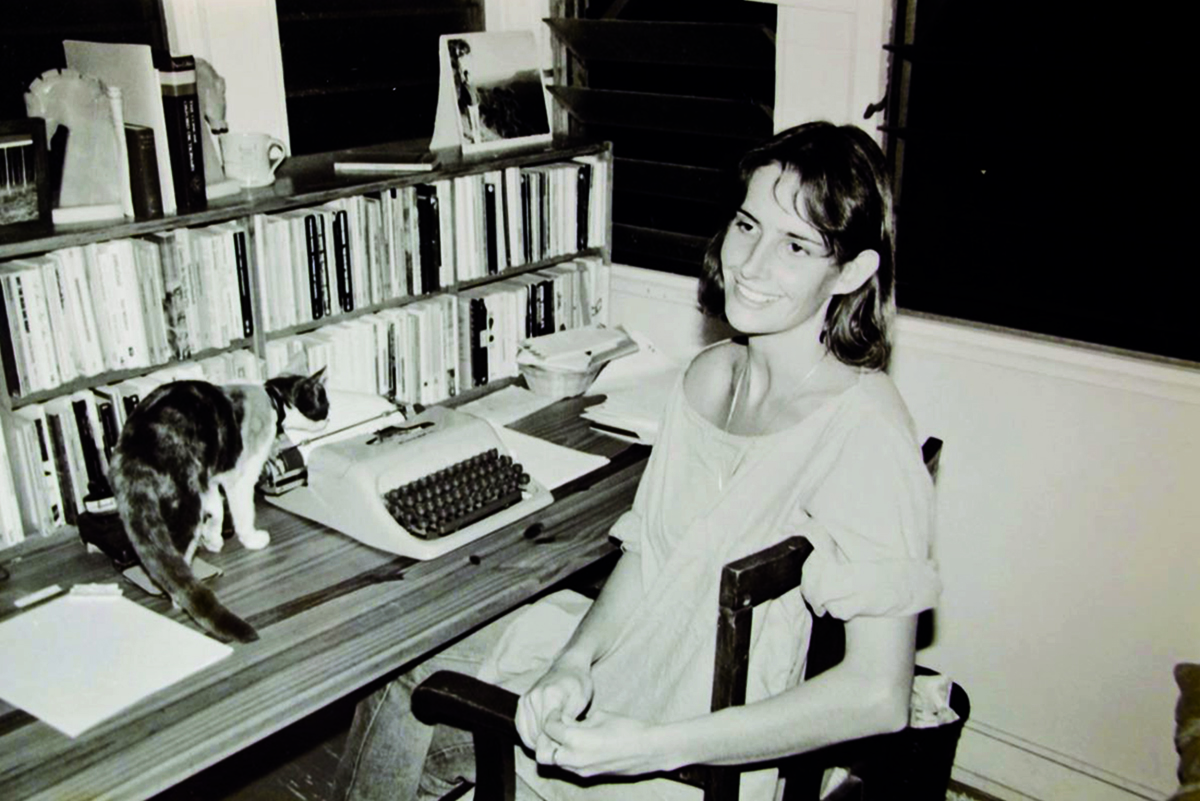

Leaping into Waterfalls: The enigmatic Gillian Mears

Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 360 pp

Hand-to-hand combat

In 2011, Bernadette Brennan convened a symposium on ‘Narrative and Healing’ at the University of Sydney, an opportunity for specialists in medicine and bereavement to meet writers with comparable interests. Helen Garner, for example, spoke about Joe Cinque’s Consolation. The day included an audiovisual piece about death as a kind of homecoming, with reference to the prodigal son, and exquisite photographs, including a picture of an elderly Irishman wheeling a bicycle with a coffin balanced on the seat and handlebars: austere and moving, a vision of austere and careful final transportation. Since 2011, Bernadette Brennan has written two literary biographies: A Writing Life: Helen Garner and her work (2017); and the wonderfully titled Leaping into Waterfalls: The enigmatic Gillian Mears. As with the Symposium, each biography is a genuine enquiry, a gathering of unexpected elements, and an invitation to later conversation. Brennan writes of Leaping into Waterfalls as an extension of a conversation she had with Mears in 2012. The Mears biography is certain to be a talking point for years to come.

Mears, born in Goonellabah, New South Wales in 1964, was intensely rural and Australian, but she always had an international perspective because of her parents’ English and South African origins. As a child on a family visit to the Acropolis, she souvenired potsherds. In her first novel, The Mint Lawn (1991), she wrote that ‘growing up in a country town organises your childhood and your life. And how unfair that is … it traps you into peculiar patterns of passivity … girls could only be involved in a limited number of interests: marching, sex, horses, Christian youth groups.’ In Grafton, Mears chose horses but also writing – conspicuously absent from this list of activities. But she defied entrapment. Her horizons were broad. Late in her life, in very poor health, she drove long distances in an old ambulance, often camping alone. Her literary influences were similarly unconfined; they included Carson McCullers and Marilynne Robinson. Brennan notes that Raymond Carver spoke to her writing class at the NSW Institute of Technology (now UTS).

In 1985, at twenty, she married her high-school English teacher. The marriage ended within five years, but it brought her back to her girlhood town and back into the complicated dynamics of her family – the allegiances of sisters, the seemingly wistful, kind father, the restless mother who died relatively young, at fifty-five, in 1991. In her self-described ‘family essay’, ‘Southern Hemisphere Human’, Mears portrays ‘the centre of the family which rather than folding calmly around itself, seethes with angers and misunderstandings it sometimes seems impossible to bear’. This story is about a specific rupture in Mears’s family, but one of the achievements of Brennan’s biography is the charting of a family with deep and difficult attachments, hosting a writer who took note of everything: parents, siblings, friends, lovers.

‘So porous were the boundaries between her life and fiction,’ writes Brennan, ‘that during the course of my research I often became confused. Had I read about certain events or conversations in a story, novel, letter or diary?’ This porousness caused a good deal of distress to people who found versions of themselves in Mears’s work, or who believed that she had appropriated their memories and material. Pity the ex-husband who saw ‘blackness and dislike and resentment’ in her break-up novel, The Mint Lawn. Pity him further when you discover that schoolgirls carried copies of the sexually graphic novel into his classrooms, or that Mears sold photos of his grandmother to the State Library for inclusion in her archive.

Mears’s next novel, The Grass Sister (1995), is anchored in the life she led with a woman partner on her father’s property, living in caravans and planning a cottage. Mears was experiencing the early symptoms of multiple sclerosis, which would take some time to diagnose. (It appears in the form of lightning-induced paralysis in her final novel, Foal’s Bread [2011].) Like The Mint Lawn, The Grass Sister is astute, passionate, and revelatory. The novel generated a rift with her uncle because of her undisguised use of family history. It also distressed her eldest sister, a fellow writer, partly because the title was similar to the name of the work-in-progress she had shared with Mears. Mears’s use of personal material raises questions of tact, privacy, and boundaries. It lies at the heart of her writing. But there are other more valuable dimensions to her work.

Mears had a precocious and sustained talent. At the NSW Institute of Technology, Susan Hampton noticed Mears’s early capacity to structure narrative, her ‘sense of the architecture of a short story’, as Brennan puts it. Her early story collections, Ride a Cock Horse (1988) and Fineflour (1990), are remarkable for the cohesion of individual stories, for startling details, for truth of character, especially when those truths are grim, and for their insight into rural life and the natural world – an ever-present quality in Mears’s writing. The first two novels, with their looser structure, shimmer on the page. The style is acutely observant, witty, and sometimes whimsical.

Both early novels have a distinct sexual frankness, consistent with Mears’s passionate life. But this may have been a deliberate liberating strategy. In a speech Mears gave in Bangalore in 1995, she spoke out against the limitations and passivity imposed upon women. In The Mint Lawn, she writes about the difference between the narrator’s life and that of the far older woman, Lettie, inappropriately married and ‘trained and raised to suffer’. Patricia Lockwood, in an essay in the 12 August 2021 issue of the London Review of Books, writes about the Canadian writer Marian Engel’s sexually transgressive novel Bear (1976): ‘[There was] a deep and violent sense of propriety that her generation, just as violently, was trying to cut out … The books are in hand-to-hand combat against that, and ultimately they are a triumph.’ Despite the differing time-frames and national contexts of Engel and Mears, I like to think of Mears’s books – and the books of many other Australian women writers of the past few decades – as engaged in strategic hand-to-hand combat with restrictive proprieties.

In 2008, Gillian Mears went to live in Mount Barker in order to train as a mana yoga teacher, convinced that the discipline would cure her multiple sclerosis and provide her with a teaching qualification and employment. This was not to be. The instructor was ultimately dismissive, the qualification was impossible to achieve, and her disability became more pronounced. Instead of teaching yoga, she worked on a story for children, The Cat With the Coloured Tail (2015), and finished her final, magnificent novel, Foal’s Bread. This difficult labour, undertaken in illness and solitude, resulted in a charming story and a significant and still somewhat under-regarded historical novel, her best, in her own estimation.

Near Mears’s house was a firing range. Brennan writes that ‘Mears was a gentle-mannered person, deeply in tune with the natural world, yet she was drawn to the explosive power of a rifle.’ This is a good description of her life, and one of the many contradictions identified by Brennan: Mears was, as Brennan suggests, ‘one of the most important Australian female writers of the last forty years’. She was gentle, yet she could be explosively disruptive.

The biography is exceptional. In A Writing Life, Brennan identifies the biographer as a ‘literary portraitist – [who] interprets a life through her own imaginative, cultural and political filters’. This is necessarily the case, but Leaping into Waterfalls is more than a portrait; it is a mighty and populous canvas. I recommend it to anyone with an interest in Australian literature.

Comments (2)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.