Dearly

Chatto & Windus, $27.99 hb, 124 pp

Secondary Atwood

Margaret Atwood began as a poet and transformed herself into a factory, producing work of great energy and range. Since her first collection, Double Persephone, appeared in 1961, she has published more than sixty books of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction. She is a librettist, a maker of eBooks, graphic novels, and television scripts, and, with the serialisations of The Handmaid’s Tale and Alias Grace, a beloved global phenomenon. Much of this work builds on genre fiction bones: the gothic romance, the dystopian novel, and speculative fiction. But now it has become difficult to see her poetry as anything more than an adjunct to her prose, attracting attention less because of its merits as poetry than because it is an Atwood production.

Her subjects have ranged from Canadian identity to revisionist mythologies and a laudable feminism (though she has sometimes resisted such labels). From the start, she has written in a spirit of scientific enquiry, pursuing ideas as much as emotions. But what of the other qualities poetry offers – form, music, or that uncanny attempt to express the inexpressible? Too often, Atwood’s poetry seems unmemorable and relatively shallow.

Yet unlike other poets, Atwood has millions of readers due to the success of her prose and its various adaptations. Her new collection of poems, Dearly, leads with a letter to said readers, then a poem clearly aimed at posterity: ‘These are the late poems.’ The definite article assumes she will be discussed in the afterlife – and she will be, though not primarily for her poetry, which has become a sort of repository for her restless productivity.

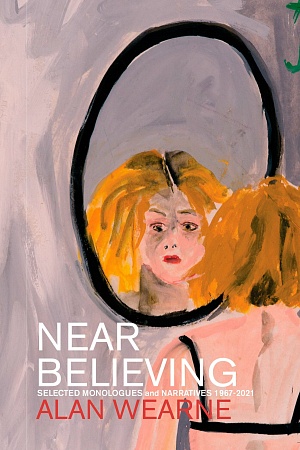

Margret Atwood at New Scientist Live, 2017 (John Gaffen/Alamy)

Margret Atwood at New Scientist Live, 2017 (John Gaffen/Alamy)

Her early work included such incisive minimalism as the following:

you fit into me

like a hook into an eye

a fish hook

an open eye

There are poems with subjects that seem hers alone, like ‘Half-Hanged Mary’, and arch retakes on the psychology of myth like ‘Siren Song,’ but across more than sixty years her verse has hardly evolved beyond the serviceable technique we could see at the start. A younger Canadian poet, Jason Guriel, has objected to the prominence of Atwood’s poetry (in the Autumn/Winter 2020 issue of the Scottish magazine The Dark Horse), calling some of her lines ‘so flat they’re basically roadkill’. More than a generational squabble, Guriel’s essay critiques a poetry thinned to its concepts. It hasn’t risked much in its subjects or offered particularly memorable lines. The plain style of Atwood’s new book resembles that of a thousand other poets writing now. Her most eloquent passages don’t really go anywhere and too often close with mild self-approval. The politics of her ‘Princess Clothing’ is as facile as the fashions it critiques:

Fur is an issue too:

her own and some animal’s.

Once the world was nearly stripped of feathers,

all in the cause of headgear.

The opinions are valid, but such prosaic language would be boring in any circumstances. Another poem improvises ‘On a First Line by Yeats’, so I looked up the original, a poem called ‘Hound Voice’, in which Yeats evokes a mysterious, violent, and primordial world in strong stanzas. Atwood’s poem, torn between environmental concern and a lament for lost meaning – ‘Everything once had a soul’ – never touches emotions deeper than a newspaper column’s. What if everything does still have a soul and she’s too unwilling to search for it?

Atwood’s short novel The Penelopiad (2005) offered a feminist revision of Homer’s Odyssey, but once one has made such a critique, where does that leave all the other resonances of myth? In Dearly, she tries again with poems like ‘Cassandra Considers Declining the Gift’: ‘What if I didn’t want all that – / what he prophesied I could do / while coming to no good / and making my name forever?’ Notice how bland and functional the lines are. A more compelling use of mythology can be found in The Scattered Papers of Penelope (2009) by the late Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke, who writes from inside the artist’s wound, probing its psychic origins. Atwood comes closer to such intimations in ‘Cicadas’, a poem about music and being:

This is it, time is short, death is near, but first,

first, first, first

in the hot sun, searing all day long,

in a month that has no name:

this annoying noise of love. This maddening racket.

This – admit it – song.

Nothing in Dearly is unintelligent, nothing objectionable politically or otherwise, but too little is vulnerable to experience or open to articulate emotion. Too little of it produces anything deeper than a nod of recognition and mild approval. Only when she turns to actual loss in elegies for Graham Gibson, her partner of many years, does Atwood touch a nerve:

The red light changes. Darkness clots:

it’s him all right,

not even late, his cane foot

hayfoot, straw,

slow march. It’s once

it’s once upon

a time, it’s cane

as tic, as tock.

Here, emotion resists speech, creating a tension she too rarely achieves in other poems. We can also find a touching understatement in her ‘Invisible Man’: ‘You’ll be here but not here, / a muscle memory, like hanging a hat / on a hook that’s not there any longer.’

Other good poems include ‘One Day’ and ‘Dearly’, which finds its grief in a word. The collection will be approved because it contains the work of an important writer, but readers who really care about poetry, who want charged language moving into another dimension, lines they cannot forget or durations of sound and sense that shiver their timbers, will find too little in this book that really compels attention. These are symptoms of conformity more than poems, unchallenging additions to the so-called poetry of our time.

Comment (1)

'All hearts float in their own / deep oceans of no light, / wetblack and glimmering, /

their fourth mouths gulping like fish.'

Maybe this new collection isn't one of Atwood's best – maybe it's no good at all – and I can appreciate that it may be annoying that her poetry (whether good or not) gets a lot of attention because of the success of her prose. Sure, her poetry won't be to everyone's taste. But I believe that writing off all the poetry she's published for any one of these reasons is unnecessary and unwarranted. (For the good stuff, I recommend 'Margaret Atwood, Eating Fire: Selected Poetry 1965–1995'.)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.