Car Crash

Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 304 pp

Lech Blaine’s double life

Young writers may turn to the page for catharsis – for writing-as-therapy – but that’s not why we read them. The ageist view, that a writer mustn’t pen their memoirs until they are older and learned, neglects the breadth of excellent work by precocious writers who have a story to tell. Naïveté and inexperience can enchant, sometimes more so than brilliant craftsmanship or intellectual maturity.

Lech Blaine’s memoir, Car Crash, introduces another young author to a corpus of young Australian essayists and memoirists, which includes Oliver Mol (Lion Attack! [2015]), Bri Lee’s (Eggshell Skull [2018]), and the collected works of Luke Carman and Fiona Wright. To different degrees, these writers attempt to document a turning point in their personal lives. For Fiona Wright, the trigger was coming to terms with, and learning to talk openly about, her eating disorder; Luke Carman had a psychotic breakdown after his marriage failed; Bri Lee, as a former lawyer, wrote from a personal perspective about the ways in which the Australian legal system handles sexual abuse cases; and Oliver Mol, the Aussie hipster Everyman, related how migraines prevented him from reading, writing or – the horror! – using his smartphone.

Blaine’s turning point was a devastating accident that killed three of his friends. Overnight, his carefree youth was obliterated, and the young man soon discovered how poorly a masculine society full of slogans such as ‘harden up’ and ‘she’ll be right’ had prepared him for dealing with tragedy.

The book opens on 2 May 2009, when Blaine was involved in a car crash near Toowoomba. In a scene that feels highly metaphorical, Blaine escapes the car crash and watches amid the tragedy gawkers as his six friends remain trapped beneath the wreckage. ‘The car crash hadn’t occurred to me,’ Blaine later reminisces. ‘Not in the same way as to the others. I was a bystander to the end.’ By establishing himself as an onlooker to his own tragedy, Blaine cleverly frames the dramatic arc of his survivor’s guilt.

During the course of the following days, he receives the news in a state of deep shock. Three friends are dead. Tim, his best mate, is comatose. Dom, the driver of the car, must endure a trial for his role in the death of his passengers (he was ultimately acquitted of dangerous driving and of dangerous driving causing death and grievous bodily harm). The rumour mill is already corrupting the tragedy with fanciful retellings. Although it’s later confirmed that the P-plate driver was sober and driving under the speed limit, hostility toward young male ‘hoons’ runs deep in Australian society. As Blaine writes: ‘The driver was drunk and speeding, clearly. At some point he’d been blindfolded from behind. The front passenger – me – yanked on the steering wheel. We were committed to a suicide pact. Witnesses saw ziplock bags of weed on the back seat.’

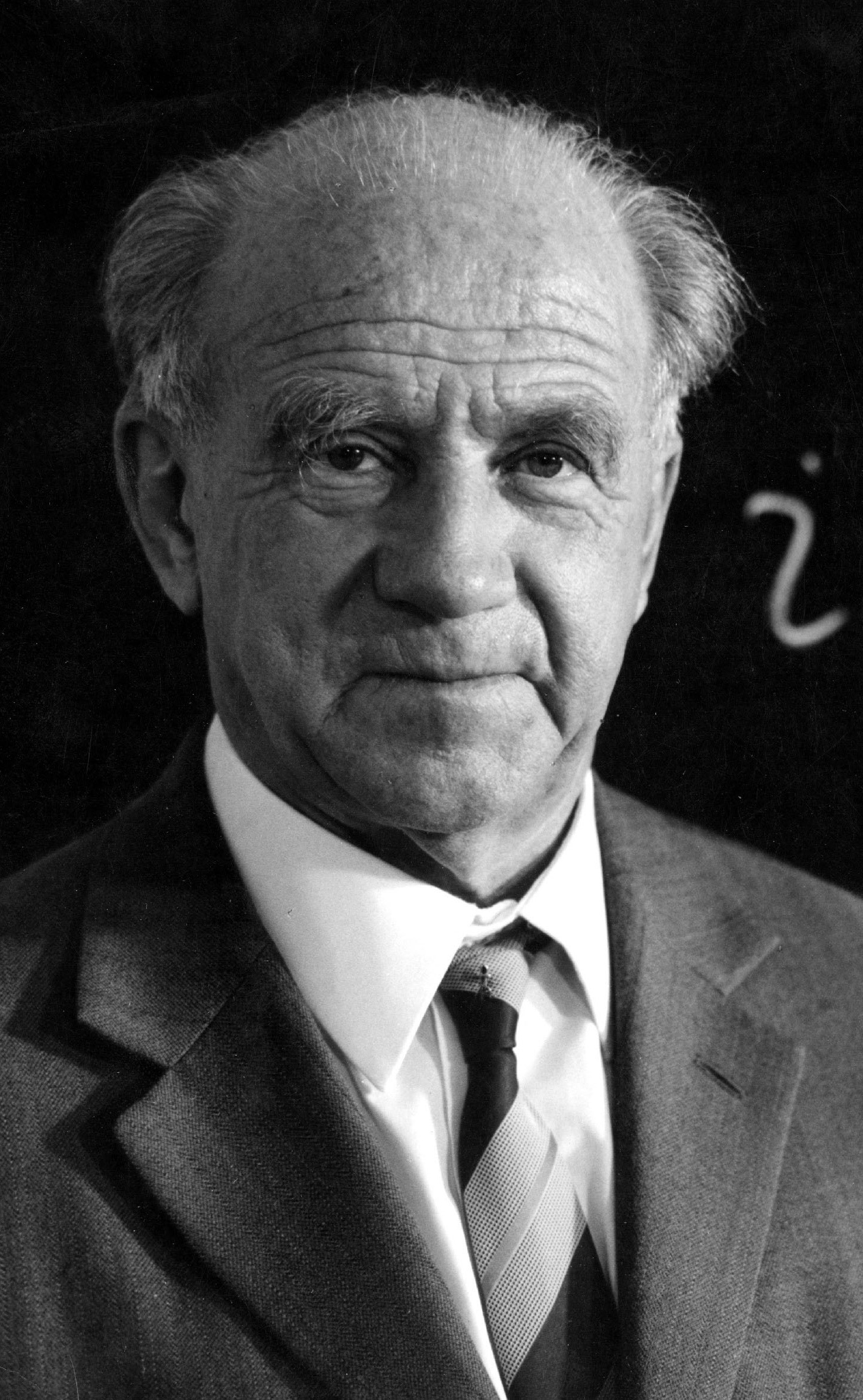

Lech Blaine (photograph by James Brickwood)

Lech Blaine (photograph by James Brickwood)

Afterwards, the crash casts a long shadow over Blaine’s sense of self. The book flicks between episodes before and after the crash, filling the reader in about his literary ambitions, his torrid journey from adolescence to adulthood, and the beginnings of a Martin Edenesque romance with the cultivated Frida.

Blaine adopts the good old tortured artist archetype, with an outback spin. Since reading Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Blaine has considered his larrikin lifestyle and literary ambitions as being diametrically opposed. He lived a double life. He describes himself as ‘poet moonlighting as a hoon’, a stranger lost in a land of beer-drinking philistines. His father, Thomas, demonstrates a well-meaning inarticulacy when trying to console Blaine after the crash. ‘That’s a fuckin’ cunt of a thing,’ Thomas says. But ironically Blaine’s native tongue, an ocker irreverence, gives his writing an amiable charm and reflects the styles of artists such as Tim Winton, Miles Franklin, and Helen Garner.

As Car Crash progresses, Blaine begins to inhabit a darker territory of life. He spirals into self-renewing misfortune, involving trouble with the law, intemperate drinking habits, a failure to acculturate in Brisbane, disillusionment with his father’s ‘she’ll be right’ attitude, and alienation from his family and friends. The book’s epigraph, which presents a definition of a car crash as ‘a chaotic or disastrous situation that holds a ghoulish fascination for observers’, suggests the book is arranged as a series of smaller ‘crashes’ or aftershocks, all stemming from the original accident.

The words ‘ghoulish fascination’ lingered in my mind while I reread the opening pages of Blaine’s book. It clearly referred to the rubberneckers who huddled voyeuristically around the scene of the crash. But then I found a shadow meaning: was I, the reader, any better than a gratuitous rubbernecker? Was I drawn to Blaine’s memoir for the same trauma porn, the ghoulish fascination, of observing disaster?

The note of tragedy was not what stayed with me after reading Car Crash. Blaine’s navel-gazing keeps the stories of the other survivors remote; we never get to see their tragedies. For the most part, Blaine seems to have resented his status as ‘bystander’ – a witness, not a victim.

Blaine is the antithesis of Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus: our ‘pessimistic poet’ never reaches the epiphanic moment of heightened perception in everyday life. Instead, the book ends without closure or cure or ‘clean endings’. For Joyce, epiphanies were profound, spiritualised moments arising from banality. Blaine’s realisation is more humble: the banality of extraordinary trauma. We see glimpses of ‘subterranean pain’, of profundity, but often Blaine’s powers of self-analysis are blunted by a penchant for bravado.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.