Nimblefoot

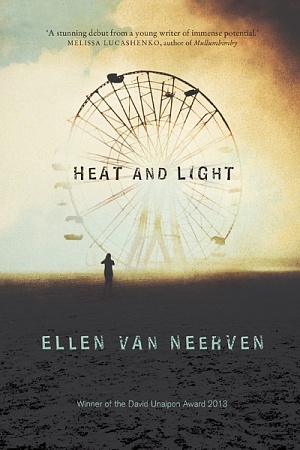

Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 305 pp

Reckless as a rule

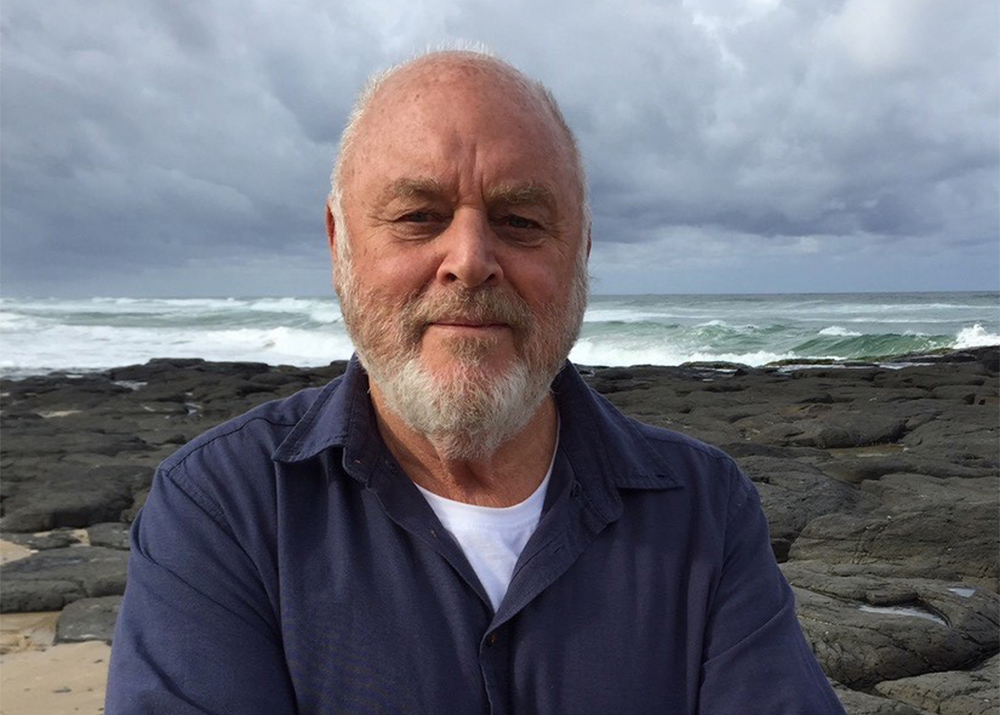

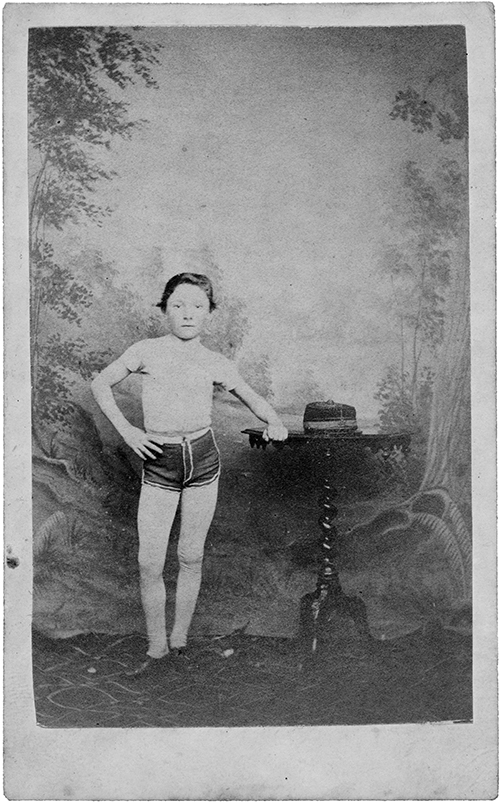

The National Portrait Gallery owns a minuscule sepia studio photograph titled ‘Master Johnny Day, Australian Champion Pedestrian’. From this curious gumnut, Robert Drewe has created a sprawling multi-limbed eucalypt.

In a few months, Drewe will turn eighty. He is part of an extraordinary cohort of Australian novelists born in 1941–43, including Helen Garner, Roger McDonald, Peter Carey, Murray Bail, and Janette Turner Hospital. We now have an opportunity to discover what late style means for these heavyweights.

For Drewe, on the evidence of Nimblefoot, it means intensity rather than looseness. Nimblefoot contains more stuff than Colonel Pewter’s holdall, including Rechtub Klat, Noongar techniques for catching marron, the incineration of a scale model of the royal vessel Galatea in Bendigo, the ‘Lunatic’s Douche’, management of bubonic plague in Western Australia, and Dante Rossetti keeping pet wombats in his London garden.

The book opens with a strong, strange animal interaction – out of register, toppling expectations. The first sentence reads: ‘The Moscow Maestro is wearing a nanny goat around his neck like a scarf.’ It is a gambit that Drewe has used previously. Think of the lion barking at the start of Our Sunshine (1991). Wasn’t that supposed to be a Ned Kelly book?

Immediately we recognise that Drewe’s powers of imagination are undimmed. The bravura manoeuvre of placing a circus at Glenrowan in Our Sunshine and reframing a well-worn tale is echoed as once again he mixes ideas and smiths images to revivify history. The kernel is the little-known story of Day, a race-walking prodigy. By the age of ten Day had won 101 races at a time when punt-struck Australians were betting large sums on pedestrianism. As the sport’s prominence ebbed, he turned to horseracing. In 1870, aged fourteen, he piloted bay gelding Nimblefoot to victory in the Melbourne Cup – then faded from the historical record, freeing Drewe to pursue his fictional fancies.

Master Johnny Day, Australian Champion Pedestrian c.1866 by an unknown artist (National Portrait Gallery of Australia)

Master Johnny Day, Australian Champion Pedestrian c.1866 by an unknown artist (National Portrait Gallery of Australia)

In Nimblefoot, Day is whisked away to a brothel after winning the Cup by a group that includes Queen Victoria’s son Prince Alfred and Captain Frederick Standish, Victoria’s Chief Commissioner of Police. After Alfred rapes and injures a young girl, Standish murders her and an African American servant. The teenage jockey, witness to these atrocities, escapes before he can be killed, scarpering to the familiar Drewe territory of Western Australia. Here he falls in and out of employment, luck and love, encountering numerous colourful acquaintances, the kind that Henry Lawson called ‘common brother-sinners’.

Reading a new Drewe novel feels like opening another chapter of a narrative that has unfurled over almost five decades, intensified by the reappearance of familiar tropes. Like Molloy in Grace (2005), Day can’t swim and is anxious around water: ‘he wasn’t sure about an element that required not only mastery but surrender’. A minor character collects the skulls of small native animals; skulls and bones recur in Drewe’s fiction. The outrages perpetrated by Standish and Alfred exemplify the defects Drewe habitually locates in the empire or its representatives. The malign hitman who stalks Day reminds us of Eric Cooke in The Shark Net (2000).

The narrative skips from first to third person, occasionally within the same chapter. Drewe sporadically interleaves fragments from newspaper stories, advertising copy, a promotional poster. Famous figures abound, slightly off-centre – as in George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman books or Don DeLillo’s Underworld (1997). (But then, in Fortune [1986] Drewe warned us that in a country with a small population, ‘everyone over thirty knows everyone else.’) Here is Adam Lindsay Gordon, depicted as he might have described himself, ‘Hard livers for the most part, somewhat reckless as a rule.’ There is Lola Montez, performing the notorious Spider Dance. A set piece concludes with a hungover Anthony Trollope visiting an abattoir and vomiting on his boots. And as the character Day says to Trollope: ‘Wait, there’s more.’

This is a book of abundance. A true picaresque – episodic, rambling, with the central character acted upon rather than agentic, buffeted by fate. Every detail is detailed, every particular particularised; this might be delightful or tiring, depending on your preference. Michael Ackland wrote in Westerly of Drewe’s ‘abiding ambivalence towards history’, that ‘his novels are concerned with defamiliarizing the established record, with highlighting lacunae and neglected episodes or aspects’. I thought of eutrophy, the state of bodies or water that have too many nutrients and not enough oxygen. This quest to conjure depth and vibrancy is freighted with a lot of information that might be shaded as extraneous, and it can be difficult to discern the telling detail from the decoration.

For all that, what a joy to spend time with a writer who does not give us a dog but ‘a loony border collie with one blue eye, the other brown’. After Day’s mother miscarries there is, ‘Dry lightning menacing our house and a carpet of blood from front door to back’. A stock character is brought to life: ‘the rare glimpses of him in shirtsleeves revealing dark armpit stains, stained orange from a strong anti-perspirant ordered from the London perfumer Eugene Rimmel’. Drewe searches always for the startling image, such as horses still in harness that have plummeted from a pier, ‘in petrified mad gallop on the seabed two fathoms down … blowfish and small octopuses politely reduced the horses from the lips and nostrils backwards’.

Wilson Buntine, purportedly the first-ever Black student of Hale School, is one of many carefully crafted characters that appear, seem likely to have narrative significance, then wander off-stage – which is the way things work in life, certainly, but not always in compelling fiction. We are told that Buntine is named after two houses at the school. Hale old boy Drewe would know they are names of twentieth-century headmasters, whereas we meet the student in the 1870s.

Perhaps this dip into asynchronism flags that the novel’s relationship with time unravels in the last portion. My assumption based on the flow of action was that the period of Day’s pursuit in Western Australia lasted a year or less. However, there are references to Ned Kelly’s beard, the Catalpa rescue, and Monet’s move into Impressionism, which suggest that the action sprawls over most of a decade. Then when Standish dies, the wrong date is given and probably the wrong year. Why break some rules of historical veracity and not others? What are these choices telling us?

Twenty years ago, Drewe postulated that there are two Australian myths always fighting for precedence in our literature – the Myth of Landscape and the Myth of Character. Both are on bright display in this late novel. Many readers will be glad they can still accompany him as he referees the wrestle.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.