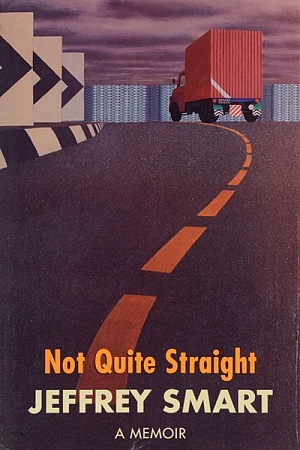

Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller

Corsair, $32.99 pb, 224 pp

‘Those shelves have power’

The Nile runs straight through the middle of Cairo, from south to north like a grand zip. In the middle of this citied stretch of river there is an island known colloquially by the name of the suburb that crowds it: Zamalek. Once the grounds of a summer palace, the island became a colonial stronghold in the 1880s, when an extravagant leisure club was built for British Army officers, replete with croquet lawns, a polo field, and pony stables. Now, Zamalek is a restless mix of affluence and decay: home to old money, new expatriates, and crumbling art-deco apartment blocks – the last gasp of Nasser-era rent control. Embassy gardens thrive behind concrete walls and razor wire, while national service recruits doze in the heat, chins propped on the barrels of their AK-47s. American fast-food chains rub greasy shoulders with antique stores full of French rococo and faux-Napoleonic gilt. The ponies outlasted the British Empire, and can still be booked for riding lessons, but the summer palace has been swallowed by a Marriott Hotel. And on the busiest street of this well-storied isle – where the everyday traffic is as loud as a rock concert – there is a bookshop.

I stumbled across Diwan on my first night in Cairo, and for the two years I called Zamalek home, I lived a short walk away from its grand glass doors. The store was the centre of my mental map, a pocket of alphabetised calm in the city’s ever-roiling chaos – so ferociously air conditioned my glasses would fog. It was the place I’d arrange to meet new friends so we could browse our way to conversation, and where I would go to people-watch on lonely nights (lurking in the divide between the Arabic and English language books was the rarest of Cairo commodities, a non-smoking café). The store was the landmark overseas visitors would use to trace their way back to me, or – more often than not – the place they’d get lost along the way, returning with far too much literary luggage.

The booksellers of Diwan filled my hands with stories of Cairo – raw-hearted, past-bound el-Qahira – and those stories helped me to understand my transitory place within it. I left Australia with two boxes of books; I sent home more than a dozen. But I never said goodbye. I left Egypt as the pandemic hit – a rush of packed bags amid rumours of airport closures. I intended to return. Now, with those intentions scuttled, it is a quiet delight to be able to revisit my favourite Zamalek haunt in Nadia Wassef’s bittersweet memoir, Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller. ‘Diwan isn’t a business,’ Wassef writes. ‘She’s a person, and this is her story.’

Wassef founded Diwan in 2002, alongside her sister Hind and their friend Nihal Schawky: three women with a wildly hopeful vision for Egypt’s literary future. ‘We launched Diwan in a culture that had stopped reading,’ Wassef explains. ‘Education had emphasised rote memorisation and discouraged freedom of thought. Readers were alienated at every turn ... literature died many successive slow and bureaucratic deaths.’ The country was entering its third decade under Hosni Mubarak’s listless, censorious leadership, and national illiteracy levels were at a record high. Egypt’s publishing infrastructure had largely crumbled, and state-printed books were flimsy creatures, stapled together like pamphlets (and largely propagandist). Bookshops, Wassef recalls, were either government-run, glorified newsagents, or ‘tomb-like’ places where the books desiccated on the shelves. ‘Starting a bookshop at this moment of cultural atrophy seemed impossible and utterly necessary.’

Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller is the story of what happens when dauntless optimism collides with bureaucratic torpor – a tale of shake-ups and shakedowns. ‘We had no business plan, no warehouse, and no fear,’ Wassef writes of herself and her co-founders. Dismissed as ‘bourgeois housewives wasting our time and money’, the trio would go on to open sixteen Diwan outlets (and close six) – not bad for novice businesswomen in a notoriously corrupt and ferociously patriarchal autocracy.

There’s a long and mighty history of female entrepreneurship in Egypt, Wassef argues – it’s just unsung, a history of erasure. Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller is a potent rejoinder, but it’s not a jaunty girlboss manifesto, some kind of Cairene Lean In. Wassef is writing from London, where she relocated after the military intervention that brought to power General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi: Donald Trump’s ‘favourite dictator’. Her memoir elegises pre-revolution Cairo, those new-millennium years of reformist idealism in the lead-up to January 2011. It was a time that shimmered with possibility; if not a cultural renaissance, then the promise of one. By the time I arrived in Cairo in early 2018, that shimmer had long proved to be a mirage. The city was a hard knot of grief.

Diwan’s flagship was the Zamalek store, which opened on the former site of a men’s gym (‘I savoured the irony of our female-owned-and-operated bookstore replacing that temple of masculinity’). Wassef was the store’s English-language book buyer. Rather than a dutiful chronology, she gives us a reading experience akin to browsing. We wander from one section of the store to another – classics, parenting, art and design – each a prompt for reflection, personal and political. ‘Diwan, and Egypt, changed around me,’ the former bookseller writes. ‘As always, my shelves offered me an unexpected education on these changes.’

There are the Jamie Oliver ‘Naked Chef’ cookbooks that land Wassef in strife with the Egyptian censors (‘Little did I know then how much angst this particular chef’s metaphoric nudity would cause me’); and the coffee-table books that are increasingly popular in Cairo’s gated communities; a new kind of home decor for a new kind of insular wealth. In the months before the Egyptian revolution, Wassef watches as sales of self-help books skyrocket: ‘Egyptians, tired of waiting for the government to help them, looked for arenas where they could help themselves,’ she writes. (Egyptians, Wassef claims, invented the self-help genre – the morally instructive Maxims of Ptahhotep was written sometime between 2400 and 2500 BCE. In my time in the city, the runaway bestseller was Why Men Marry Bitches: A guide for women who are too nice by Sherry Argov).

‘Those shelves have power,’ a crotchety customer warns Wassef: ‘use it wisely.’ She feels the weight of that power, particularly when it comes to stocking Diwan’s ‘Egypt Essentials’ section. For how do you tell the story of a place that stands in the literal and existential shadow of the Pyramids? Romanticised, mythologised, colonised, nationalised, pathologised, and plundered: Egypt defies the easy slipstream of narrative. Nostalgia is a national pastime, but every mind conjures a different country, so memory is a conversational battlefield. ‘Searching for something, I gathered images of my home in one place,’ Wassef explains. ‘Our eclectic collection would introduce the coloniser to the colonised, the historians to the novelists, the locals to the outsiders.’ It was a collection as much for Egyptians as tourists; a chance to reclaim a history too long defined and gatekept by others. ‘Westerners created Egyptology then taught it to the Egyptians,’ Wassef laments. ‘There’s a double irony in the way that colonialism first severs us from our past and then forces us to turn to the colonisers for knowledge of that very past.’ (It is perhaps no accident that Edward Said, author of Orientalism, 1978, and founder of postcolonialism, spent his formative years in Zamalek.)

I spent hours browsing in Egypt Essentials, revelling in its kaleidoscopic portraiture. Wassef’s ‘modern mythology’ made space for sumptuous catalogues of King Tut’s tomb jewellery, Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile (1937), and fictional forays into Cairo’s Queer underground (see In The Spider’s Room, 2017, Muhammad Abdelnabi, or Guapa, 2016, Saleem Haddad). Naguib Mahfouz’s entire back catalogue was there – in all its capacious, Nobel Prize-winning glory – next to photo-essays on revolutionary graffiti, joyful histories of Egyptian cinema, and illustrated maps of the Valley of the Kings. There were memoirs from Jewish families exiled by Nasser in the 1950s (The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit, 2007, Lucette Lagnado), and the diaries of feckless nineteenth-century British toffs who shipped parlour pianos and iron beds across Europe to provision their Nile cruises. It was on the shelves of Egypt Essentials that I discovered Sex in the Citadel: Intimate life in a changing Arab world (2013), by Egyptian-British journalist Shereen El Feki; the raw-toothed feminist fiction of Nawal El Sadaawi; and my favourite Egyptian fiction: Waguih Ghali’s Beer in the Snooker Club (1964).

Ghali’s heavily autobiographical novel was the first book I bought at Diwan, and I read it in one jetlag-jittery jag on that first night in Cairo, listening to the party boats echoing up and down the river. It’s the story of a young man from a bankrupted branch of a wealthy Cairene family, who carouses his way across the city while his relatives pick up the tab to keep the old-money honour intact. The man can’t take a job – it would give the game away – so he’s stuck in a kind of indolent rage, a septic inertia. Around him, Cairo is also stuck, nursing a vicious post-colonial hangover

Beer in the Snooker Club was Ghali’s only novel (he died by suicide in 1969), but his send-up of Cairene classism still echoes. ‘While my staff and I inhabited the same city,’ Wassef writes more than five decades later, ‘our cities were not the same.’ There’s no escaping the fact that Wassef comes from wealth; that she had the means to open a luxury-goods store in the heart of well-monied Zamalek, and the choice to leave it – and Egypt – when it suited her. There’s also no question that, for fifteen years, she worked herself into the dust to make Diwan viable. Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller is frank about both: the work, and the privilege underpinning it.

Arabic books, for example, consistently outsell English language books in the store, but it’s the imported books that keep Diwan’s doors open; an uneasy cultural bargain with a tenacious whiff of empire. ‘Our local customer-service staff sold foreign books that, in some cases, cost more than their modest salaries,’ Wassef admits. We watch the women of Diwan sew the trouser pockets of store uniforms shut – lest their employees nick any loose notes – and then travel home in their slick SUVs, chauffeured by personal drivers. The Cairo I recognise is here. I bought those glossy international books, and had change to spare for carrot cake. It would be disingenuous to pretend otherwise.

Diwan’s newer outlets are in the city’s mega-malls, out on the edge of the desert, where artificial ice rinks keep captive penguins, and middle-class consumers go home to compound life. Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller is more than the tale of a bookstore: it’s a portrait of the city’s fast-fading micro-economies, like Zamalek, where wealthier families have visible, tangible relationships with neighbourhood traders: the family butcher, the baladi bread maker, the street-side shirt ironer. It’s a life that’s easy to sentimentalise – and Wassef does – an amiably patrician model of inter-generational patronage. But as the New Administrative Capital (NAC) takes shape an hour east of Cairo – a city built entirely of high-walled enclaves – there’s an accelerating sense of civic fracture. It’s hard to care about something (or someone) you don’t see.

I used to run a weekly creative writing workshop in Cairo around the corner from Diwan, and I’d often begin by asking my fellow writers to pen love poems to their shape-shifting city. ‘Mish mumkin,’ they’d say. ‘Not possible.’ And then they’d go on to write extraordinary pages, full of fury and forgiveness, and scabrously funny (Oh, Cairo, how you piss me off!). ‘Diwan was my love letter to Egypt,’ Wassef writes. ‘And this book is my love letter to Diwan.’ Like those mish mumkin poems, Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller is honest about its city – the class-riven cruelties, the misogyny, the revolution’s squandered opportunity – but it’s also full of broken-hearted love: ardent and irreverent (and elaborately sweary as befits any self-respecting Cairene; my running list of Arabic curses tops a dozen pages). ‘Those of us who write love letters know that their aims are impossible,’ Wassef writes. ‘We try, and fail, to make the ethereal material.’ Impossible perhaps, but if you find yourself in Zamalek, you can still visit Diwan. For now, at least, she is still there.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.