Son of Sin

Affirm Press, $29.99 pb, 288 pp

Desire’s other face

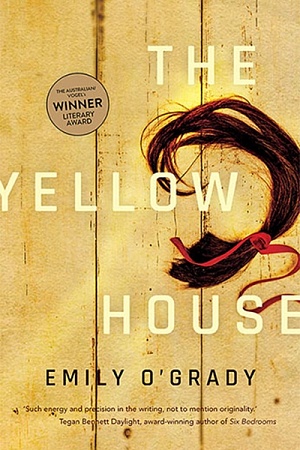

The first thing readers will notice about Son of Sin is the snake coiled across the front cover, its inky scales contrasting with the hot pink background, at once disquieting and strangely beautiful. This striking image sets the tone for the rest of the novel, which is the prose début for Sydney poet and social commentator Omar Sakr. The text provides a disarmingly frank perspective on sexuality, race, and shame in contemporary Australia.

The protagonist is Jamal, a bisexual Arab Muslim coming of age in Sydney’s western suburbs. He struggles to embrace his attraction to men in a religious and familial milieu where homosexuality is seen as ‘the ultimate taboo’ and where men are belittled for undertaking activities not traditionally regarded as masculine (such as reading). Jamal’s mother is homophobic and abusive; his mates are not shy about expressing anti-gay sentiments. Jamal routinely observes the use of violence to instil fear within, and exert control over others.

Throughout the novel, Jamal grows from an awkward teen to a twenty-something whose self-assuredness is slowly blossoming. He travels from New South Wales to Turkey and back: learning about his family’s history, having unexpected but not unwelcome sexual encounters, and striving ‘to resist definition, to be only what he wanted to be, when and as he pleased’. The identity labels that are placed on him by others are found to be simplistic and constrictive.

Which brings us back to that cover. The snake is a metaphor for the poisonous pressure of trying to live up to the expectations of others. Sakr writes: ‘Jamal was not good, not okay … There was a snake in his eyes and it was trying to kill him.’ The reptile might be a metaphor for homosexuality and the danger that the protagonist attributes to it – a danger that is simultaneously frightening and sexy. As Jamal himself notes: ‘What is dread if not desire’s other face?’ The phallic connotations of said creature are unmistakable.

Stylistically and thematically, Son of Sin has much in common with Christos Tsiolkas’s Loaded (1995). Both focus on the sons of migrants who are coming to terms with their masculinity and attraction to men in contexts where those attributes seem incompatible. The text also invites comparisons with Michael Mohammed Ahmad’s The Lebs (2018), which was set in Sydney’s west and which revolved around a Muslim young man growing up in the shadow of 9/11 and the Cronulla riots of 2005.

Also, like those novels, Sakr’s text avoids easy answers and cheap psychologising. There are no happy endings or neat resolutions in Jamal’s quest for contentment and comfort. He ‘wanted more from home than brick and mortar. He wanted to be safe in his own body.’ Jamal recognises, though, that safety may be impossible in a country where Middle Eastern men are routinely profiled by police (this happens to the protagonist moments after he returns from an overseas trip) and which has a long, bloody history of colonialism. The young man ponders wryly: ‘How many bodies were in the mud beneath this house?’

In terms of sexuality, there is no great ‘coming out’ moment; indeed, the doors to Jamal’s closet always seem to hover somewhere between open and shut. His bisexuality is received by loved ones with either revulsion or nonchalance – sometimes both, but never surprise. Jamal’s sexual encounters crackle with a visceral eroticism, as well as a sense of connection (physical, emotional) that is otherwise absent from the young man’s existence. All sex scenes run the risk of being cringe-worthy; Tsiolkas’s The Slap (2008) offers a memorable example of this. It is a testament to Sakr’s literary prowess that he avoids that cringe factor.

Son of Sin avoids moralising about or castigating its characters. Their flaws and shortcomings are the products of their lived experiences, which range from the difficult to the unbearable. Jamal’s acceptance of and empathy for his loved ones, even when they shower him with hostility, is poignant and credible.

At times, the text becomes too polemical. Witness Jamal’s observations about the toxicity of the 2017 same-sex marriage controversy, for example:

On the table in front of them was the postal vote for marriage equality. It was important to have the conversation, every bigot and every Tumblr teen seemed to agree. Important to bellow again each hateful word in retribution or reclamation, but to bellow it, in the hope that a body somewhere could use the sound to climb out of silence …

These observations are astute and written with elegance; they evoke the emotional pain that this vote caused many queer Australians. The comments are nonetheless more suited to an Op-Ed or a thread on Twitter (a platform upon which Sakr is active) than a work of literary fiction.

Similarly, the references to snakes and a ‘figure with a black teardrop for a head’ are more redolent of magical realism than the gritty realism the novel otherwise strives for. The teardrop creature appears to Jamal during a holiday and is genuinely unsettling; it’s unclear whether it is real or imagined. Alas, the creature’s purpose within the narrative is opaque (aside from being a rather obvious manifestation of the protagonist’s personal demons) and it vanishes as quickly as it appeared, never to be mentioned again.

Otherwise, Son of Sin is a welcome contribution to the burgeoning field of multicultural Australian queer writing. Sakr is a talented storyteller with a keen eye for character development. This reviewer hopes that more prose (as well as poetry) will emerge from his pen.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.