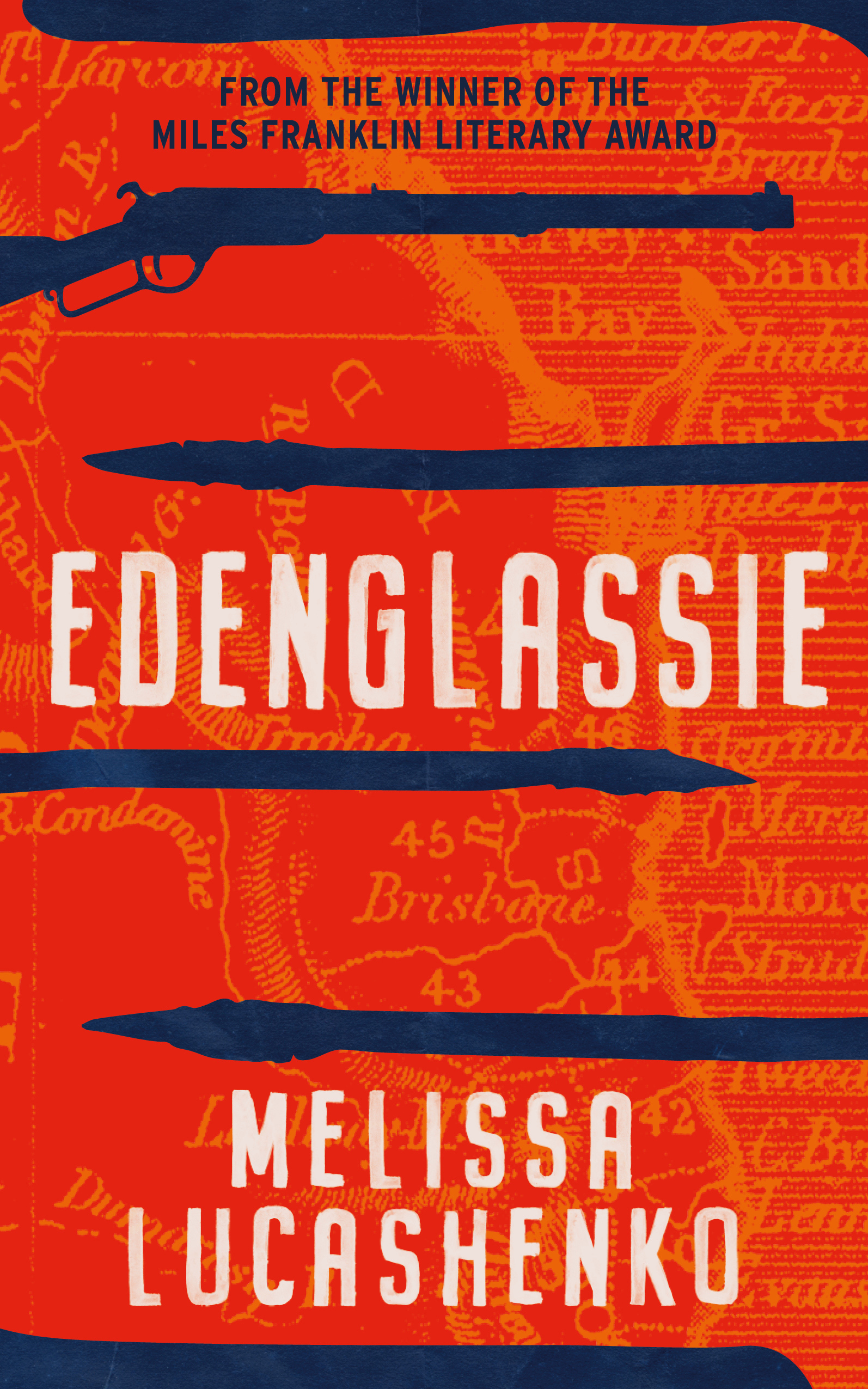

Edenglassie

University of Queensland Press, $32.99 pb, 306 pp

Where to now?

Edenglassie is the seventh novel by acclaimed Bunjalung novelist Melissa Lucashenko. Set in a brief historical window – a little-known interim of time and place after transportation of convicts had ended but before Queensland became an independent colony in 1859 – this narrative moves seamlessly between what whitefellas might call past, present, and near future. In this interface, Lucashenko creates characters that cause the reader to not only ask – what if? but also where to now?

In 2024, we meet the feisty centenarian Granny Eddie – Brisbane’s oldest Aboriginal resident; her fiery granddaughter Winona; Doctor Johnny Newman (aptly named, since he has recently discovered his Gomeroi heritage); healer Gaja Opal; and pesky whitefella journalist Dartmouth Rice. From the mid-nineteenth century we meet members of the Goorie Federation of the five Yugambeh rivers, ‘which fell like wide blue ribbons from the western ranges’; warriors Dalapai and Yerrin, his son Murree, and his wife Dawalbin; their adopted Yugambeh son Mulanyin; his lover, Nita; and the Petries, one of the first white families to claim land in Edenglassie since the invasion.

Lucashenko delves deep into themes of reciprocity, entanglement, trust, betrayal, resilience, and connectedness, set againsta visceral canvas involving actual and cultural Indigenocide1 – a genocide unique to settler-invaded colonies where the First Peoples are valued less than the land they inhabit and that invaders desire.

In the case of Edenglassie, Blak lives are not valued at all. Granny Eddie is both the glue that holds two narratives together and the thread that connects past to present to future and back again. The story begins when Granny Eddie trips on ‘the tiniest jutting tree root’ outside the maritime museum, and ‘[in] outrage the earth flung itself up at her insisting she join it’. Neither the tree nor the earth is inanimate as they draw Granny into an act of remembering where time begins ‘thumping sharply on her left temple’ and her ‘brain slowly began to crochet together a looped understanding of events’.

The events that begin looping are not just those of the present. Time shifts in cyclic arcs, but place does not. On the same ground where Granny fell, time shifts to the 1840s. Dalapai and Yerrin meet when ‘less than three hundred foreigners remained in Magandin’. Yerrin hopes that the strangers will be gone by the next Mullet Run now that ‘the sufferers’ (convicts) are no longer coming. Dalapai cautions though that there is word that ‘free white men are now welcome in our lands’. This scene is pivotal: the narrative is poised on a precipice of what if and what could have been.

After this, dual stories loop and twine. Lucashenko breaks from the temporal and geographical confinement of Western time to a mode of storying place/s that has its origins in the pre-invasion cultures of Aboriginal peoples. From her hospital bed, Granny Eddie speaks of the colonial entanglement in the early days of colonial encroachment, and warns the precocious Dartmouth to be wary of reconstructed history from ‘white historians and university lecturers overflowing with moral rigour and cultural discretion’. Granny reclaims the Goorie history of place when she asserts: ‘I’ve heard my history straight from the Old People, see. I know the truth of what was done and what was not done.’ In assuming control of what settlers call history, Granny unwrites settler claims to knowing the future, the present, and the past, and re-establishes Goorie ways of knowing, being, and telling.

Granny is joined in her hospital room by a presence who speaks of unfinished business. Initially, health professionals dismiss her sentience as a symptom of Granny's age and concussion. But here and throughout Edenglassie, Lucashenko rejects the limits of Western rationalism for characters grounded in their abilities to understand and accept all times simultaneously through embodied experiences. Granny continues to commune with her visitor, even though she is initially confused as to who it might be. This is one of two non-human but animate characters who thread through the narrative. The other is a fish – the matriarch who, without speaking, carries a message of continuance and resilience.

Concurrent with Granny’s story is that of Mulanyin and Nita. As colonial violence peaks and land theft increases, Mulanyin and Nita fall in love. Mulanyin has dreams of buying a whaleboat and going home to Yugambeh Country. But colonial law encroaches. Two hundred years later, outspoken activist Winona meets Doctor Johnny in Granny’s hospital room. The tensions and connections between the two are evidence that colonial legacies and Aboriginal resilience intertwine.

All Goorie characters are grounded in and impassioned by place – their locale – Country. There is no starker contrast between Goorie and colonial thinking than that which relates to land. Mulanyin asks Tom Petrie:

what goes through the brain of an Englishman when he arrives in another man’s country to steal his land, water, game and then with a straight face calls those he steals from thieves?

Tom answers;

It’s different, their Country holds no Dreamings to keep them at home.

Edenglassie moves in a great concentric arc with many ripples, like those in the river that is central to the action; and which is an ancient, unbroken vein that pulses life from past to present to future in a continuous cycle. Despite horrific colonial injustices meted out to Goories, this is a story of strength and love. It is an accumulation of all times – a testimony to the continuation of Aboriginal storytelling, value systems, intellectualism, scientific and technological literacy, and understandings of time, non-human agency, and Country.

Endnote

1. Indigenocide is a term first coined in an essay by Raymond Davis and Bill Thorpe, ‘Indigenocide and the Massacre of Aboriginal History’ (Overland 2001 pp 21-39) to describe systematic government sanctioned destruction of Indigenous peoples in settler-invaded colonies.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.