‘I never knew my uncle’

Pilgrimages to war cemeteries have long been part of the rituals of Australian remembrance. It is easy to understand why veterans and the parents and siblings of the men who died in war make these journeys. But why do younger generations do so today, more than a century after World War I and eight decades after World War II? These were not their battles, nor their wars. Why do they seek out the semi-sacred spaces of Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries? And why do they weep over the grave of someone whom they have never met?

The American scholar Marianne Hirsch has coined the term ‘postmemory’ to describe the relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before. As she sees it, the experiences of one generation are transmitted so deeply and affectively, through stories, images, and behaviours, as to seem to constitute memories in their own right.

I have never lost a family member in war. But I joined a pilgrimage to Ambon by the Gull Force 2/21st Battalion Association on Anzac Day to understand why children and grandchildren still make this journey, after all the veterans have died.

Gull Force was a group of about 1,100 Australians sent in December 1941 to help the Dutch colonial military forces defend the island of Ambon, in the east of the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia). The force was too small. It had little fire power and no air or naval support when a Japanese onslaught came on 31 January 1942. Most of Gull Force was soon taken prisoners of war. Some 229 were then massacred by the Japanese in the vicinity of the strategic Laha airport. The rest of Gull Force spent the war in captivity, either on Ambon or on Hainan Island, off China.

The death toll on Ambon, where prisoners were starved and worked to death, was seventy-seven per cent: it was one of the highest tolls of any group of Australian prisoners of the Japanese. Only the death marches at Sandakan were worse. The death toll on Hainan, where a third of Gull Force was sent in October 1942, was thirty-one per cent, comparable to the worst figures from the Thai-Burma railway.

For all the horror, some of Gull Force’s survivors yearned to return to Ambon after the war. This site of memory not only spoke to their own life-changing personal trauma; it was also where they fought (if only briefly) and where hundreds of Australians who died on Ambon were buried in the CWGC cemetery built on the site of the wartime camp, Tan Tui.

The dead of Hainan, in contrast, had been buried in Yokohama, Japan. Although civil war and the communist victory in 1949 precluded the creation of a CWGC cemetery in China after 1945, Gull Force survivors were enraged at the choice of Yokohama, in the land of the enemy. For all its beauty, this would never become a regular destination for pilgrimages, individual or collective.

Gull Force could not return to Ambon until 1967, given recurrent unrest in the Moluccas and tensions, including ‘Confrontation’ over the creation of Malaysia, between Australia and Indonesia. When the veterans were finally allowed in, they maintained regular pilgrimages, with breaks during the communal violence in the Moluccas from 1999 to 2002 (more of this later), and during the Covid pandemic.

From the start, the veterans had two objectives: to conduct rituals of remembrance for the dead, and to show their gratitude to the Ambonese who had helped them during their captivity, either by assisting escape attempts or by supplying food. Both activities risked Japanese retribution, even execution. The Gull Force Association thus developed significant local aid programs: developing the Ambon hospital, providing professional development, sponsoring orphan children, and so on. These two elements of pilgrimage – remembrance and aid – have continued, as subsequent generations have taken over from the veterans.

The 2024 pilgrims whom I joined almost all had a family connection with the original Gull Force. I had somehow expected that they would be children of those who died in Ambon, but they were not, for the simple reason that three-quarters of Gull Force were unmarried when they enlisted. Four of our party remembered uncles or great-uncles who had been executed at Laha. One married couple were still searching for the burial site of the wife’s uncle, who had been killed in the fighting in February 1942 on Mount Nona, which towers above the town of Ambon. But more than half of the group were remembering men who survived the war. Four had a father, father-in-law, or uncle who had been interned on Hainan. Two family groups – a father and two sons, and a mother, daughter, and niece – were descendants of men who escaped Ambon soon after the surrender and made their way back to Australia by island-hopping in borrowed boats. As these families said, they owed their very existence to these escapes.

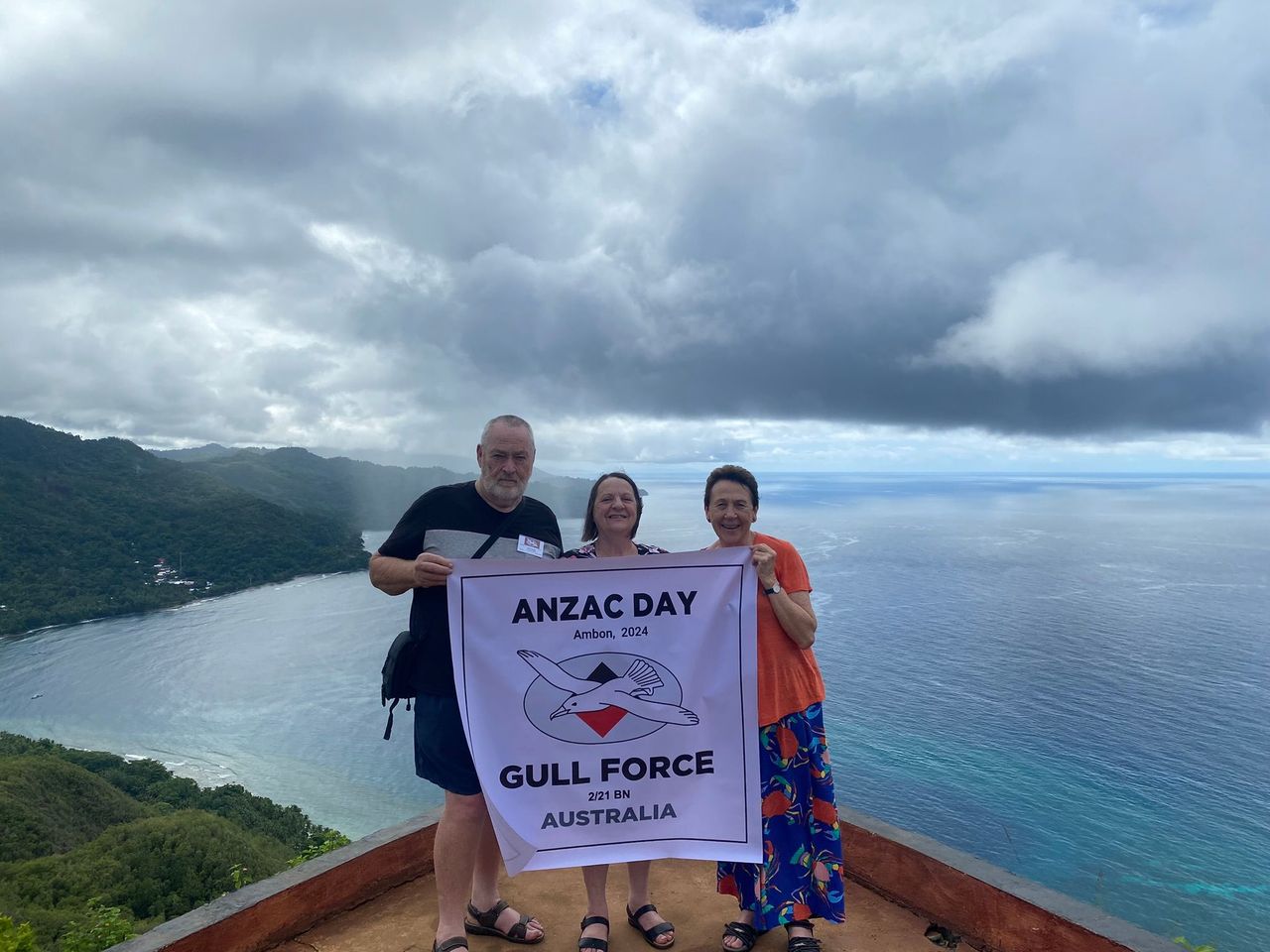

Joan Beaumont with members of the 2024 Gull Force Association pilgrimage, above Seri, Ambon

Joan Beaumont with members of the 2024 Gull Force Association pilgrimage, above Seri, Ambon

Ambon is not easy to get to. It is only a thousand kilometres from Darwin – hence, more than fifty Australians made successful escapes in 1942 – but there are no direct flights. We had to travel through Jakarta with long transit stops in a nearby airport hotel. This, then, is not an easy pilgrimage option. It is not Pozières on the Somme, less than two hours from that tourist mecca, Paris; or Ypres, in Belgium, now only a morning’s drive through the Chunnel from London, and an attractive tourist destination in itself, replete with its reconstructed medieval Cloth Hall.

We met at Melbourne Airport, with a punctuality worthy of the army. An immediate hierarchy was evident, between the first-timers and the repeat pilgrims who had made the journey to Ambon on eight, nine, ten, even fourteen previous occasions. The latter greeted the renovation of Ambon Airport (a Covid employment project, I was told) with approval. But those looking for signs of the airfield that hundreds of Gull Force had died defending in 1942 were disappointed.

Our first stop was Tawiri, a small village which houses two memorials to the Australians who were beheaded and bayoneted at Laha. The site of one of the mass graves is marked by a modest pillar on a plinth, engraved with a Christian cross. When we arrived, the site was drenched by recent rain, and the clouds threatened to burst again, so our service was brief, almost improvised: a few comments about 1942, a Christian prayer with references to duty, peace, sacrifice, and loyalty; and a poem written by one nephew in honour of a Laha victim, and here read by another: ‘I never knew my uncle. He was killed in the Second World War / He was executed on the Ambon shore … / The year was 1942 and he was 26 years old / It left the family grieving for his life could not unfold / Reginald Wade Monk was the uncle that I did not meet / I never got to shake his hand or with his children greet / No I never knew my uncle …’

Was this postmemory? Uncle Reg’s family rarely talked about his loss, but his nephew, whom I will call A, knew that his mother grieved for her brother. Uncle Reg, though dead, was a lasting presence in his extended family. Coming to Ambon, A said, brought ‘closure’ to this part of his family history, even though, he noted, he did not have an emotional response to the service comparable to that of the older B, who also remembered an uncle killed at Laha. C, too, who lost an uncle, had moist eyes as she laid a wreath of red poppies.

With a recitation of Binyon’s Ode, it was all over. We gathered up the wreath and poppies that C had helpfully supplied. They would be recycled on Anzac Day and, anyway, might be souvenired by the locals if we left them. We devoured cakes supplied by the family of our Ambonese guide and distributed gifts to the local children who were draped over the fence of the memorial space. With frisbees, sweets, soft kangaroos, koala key rings, and diverse Australian kitsch sailing through the air into the outstretched hands of children and adults, the mood became decidedly festive, even irreverent. In the midst of death, we were in life.

At a second memorial marking another mass grave a short distance down the road, it was easier to imagine the spirits of the dead restive in the dank setting. The locals speak of a giant soldier emerging from the jungle at night. We bought more cakes from roadside vendors – a contribution to the local economy, we thought, and a chance to interact with local people.

The drive to our hotel through Ambon town, with chaotic traffic, tangled overhead wires, broken footpaths, rubbish-filled canals, and multiple KFCs, confirmed that here, too, the landscape bears no echoes of World War II. Ambon town is not Hellfire Pass or the cliffs of Gallipoli, where the topography tells its own story, with little heritage interpretation.

But then, I was soon told that the Ambon pilgrimage is ‘not about the war, it is about the people’. Inheriting the local connections and the tradition of aid projects established by their forebears, some pilgrims have maintained, over many visits, deep friendships and loyalty. They greeted their Ambonese contacts with shouts of joy and warm embraces.

It seems, then, that the pilgrimage has itself become a site of memory. We might think this term applies only to physical sites and material objects – battlefields, buildings, cemeteries, and memorials – but, as the French scholar Pierre Nora, who coined the influential term lieu de mémoire, has argued, ‘sites of memory’ can include events, commemorative dates, ritual practices; even ‘the products of reflection, such as the concept of a historical generation’. These non-physical sites become invested over the years with their own meanings, symbolism, and metaphorical representation of values. Take the concept of the returned soldier that is so powerful in Australian discourse about war. It means much more than the individual veteran. It conveys the notion of a consolidated and unified collective, and a figurative and metaphorical representation of loyalty, service, citizenship, and nationhood.

‘Pilgrimage as a site of memory’ helps explain a lot. First, the choice of hotel. I was warned it would be ‘basic’. My window looked onto a wall of pipes next door. The shower never offered hot water. It flooded the bathroom when left running for the recommended ten minutes. The occasional cockroach wandered across the floor. Why were we there? Because Hotel M. is part of the pilgrimage memory. The original veterans stayed here from the 1970s on. The current owner is the son of the manager who hosted them. The banner welcoming Gull Force was draped across the hotel exterior, while Australian flags bedecked the bar (which, alas, sometimes struggled to provide enough cold beer). Comfort mattered little when memories were so rich.

Second, the pilgrimage as a site of memory explains the odd absence of interest in World War II. It was not really Fawlty Towers, but few mentioned the war, or sought to know the details of Gull Force’s history of battle and captivity. That said, the war cemetery at Tan Tui was high on our list. This houses more than 2,000 graves, including many of the 2/21st Battalion which formed much of Gull Force. It is a tranquil garden paradise, with towering moss-covered trees and graves immaculately laid out in terraced lawns between beds of tropical flowers and bushes. A memorial shelter on the first terrace provides sobering lists of the 450 Australian soldiers and airmen who died in the region and have no known grave.

On our first visit, we wandered in small groups or alone, seeking out the grave of a family member or trying to make sense of the rows upon rows of headstones. It was hard to imagine that this was the place where so many Australians starved to death, or succumbed to beriberi, malaria, or dysentery in abject squalor. Busy urban development now hems in the site. A large mosque fills the space that the prisoners of war walked across to the bay, where their latrine, which they called the Bridge of Sighs, stretched out over the water. Two of our group, whose grandfather had escaped in 1942, found the cemetery ‘significant’, but doubted that their children would make the effort to come.

We visited Tan Tui again on Anzac Day. It was a dawn service, and at 5 am several mosques in the vicinity issued amplified calls to prayer. The tsunami of sound washed over the graves of the long-dead Christians triggering at least one set of pursed lips – although another member of the group said, ‘We must all live together … they won’t last long.’ Indeed, the call to prayer soon gave way to triumphant roosters and a magical bird chorus.

Gull Force Association had pride of place at the ceremony, on seats drenched with overnight rain. Several pilgrims wore their relatives’ medals. I muttered gratuitously that in Canada this is prohibited while in Australia it is permissible, so long as the medals are worn on the right side. Perhaps another ten to fifteen Australians were present, as well as the pilgrimage twenty.

The service, led by Australian officials flown in from Jakarta and Makassar, followed a World War I template: Binyon’s Ode, the Last Post, Reveille, John Macrae’s ‘In Flanders Fields’, and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s exhortation to the mothers of Australia to ‘wipe away your tears; your sons … have become our sons as well’. The humidity aside, no one would have guessed that we were at the site of one of the great tragedies of the Pacific war. Some words were delivered in Indonesian, for the benefit of the Indonesian officials present, but the rituals were another language culturally, and heavily Christian.

The discourse, as ever, was one of sacrifice. Certainly, Gull Force had been sacrificed when it was dispatched to Ambon in December 1941 with absolutely no chance of stopping the Japanese attack. But ‘sacrifice’ was employed in a reflexive sense. The soldiers made a sacrifice, of themselves, it seems. They were not sacrificed by Australia’s military leaders and their flawed strategic planning.

On Anzac Days in the past, Gull Force moved at the conclusion of its Tan Tui rituals to the nearby Indonesian Heroes cemetery. There, they paid tribute to the soldiers of the Indonesian army, many of whom had died when suppressing the Moluccan secessionist movement in the early 1950s. But this reciprocal honouring of each other’s dead no longer occurs – though no one seems to know why, or even knows that it ever happened. So, gathering up our recycled wreaths and poppies (including the spares provided by the optimistic Australian consulate), and pausing for the obligatory cheerful group photo, we returned, with guests in tow, to our hotel for the gunfire breakfast. The familiar fried eggs, fried rice, toast, and omelettes were supplemented by pastries and the traditional rum.

Fortified, we visited Kudamati, the place where an Australian soldier, Bill Doolan, made a suicidal last stand in a banyan tree on 1 February 1942. The banyan tree is long gone, but Doolan lives on in Ambon folklore. A first memorial was unveiled here in 1968, but in 2013 it was joined by a larger memorial. Conceived by the Gull Force Association and funded by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (as so many of the memorials of the recent memory boom have been), this installation is notable in that it commemorates the living, not the dead. Like many Great War memorials in Australia itself, it honours those who volunteered to fight, and survived. ‘Somewhere,’ the group leader told me, ‘we wanted our fathers’ names to be seen – a place where we could commemorate those who returned home.’

Here again, we might see postmemory: not cross-generational trauma but pride in a family’s record of military service and affirmation of its place in the national memory of war. Children and grandchildren paused to have their photo taken, sticking a poppy onto a name with blue tack and pointing to it. ‘Is not the poppy for the dead?’ I asked. ‘No,’ D said, ‘it is more than that. It is for remembrance.’

This was the extent of such rituals, at least in the formal program. One day we stopped on a cliff top with a panoramic view of the southern coastline from which more than twenty Australians set sail for Darwin in the immediate aftermath of Gull Force’s defeat. But as we all posed for photos with the Gull Force banner fluttering in the breeze, the view that invested the site with wartime significance became the backdrop.

Only the family of one man who escaped made the journey down to the small fishing village of Seri below. The son and grandsons had struggled to articulate their reasons for coming to Ambon (they were all first-timers), but here, at Seri, the story handed down to them became real. The hills above were so rugged, the village so small, even today, that it must have been very difficult to find in 1942. And Darwin seemed a long way away across the glittering sea. How could you not be in awe of young men who took the gamble of eluding the Japanese?

Yet the spell was soon broken. ‘I bet this rubbish wasn’t cluttering the beach in 1942,’ son E said. Neither, I thought, was the beachfront chapel boasting a more than life-sized image of Jesus’s face and blasting what seemed to be Ambonese Hillsong at the foreign intruders. Grandson F thought he might be stabbed. We did not linger long.

The rest of our five days in Ambon were spent in sightseeing or in local philanthropy. One day we stopped at a tired resort for lunch and a swim. I peered out at the bay that Australians had sailed across, masquerading as Ambonese fishermen, under the nose of patrolling Japanese naval vessels. Down the coast was Paso, the strategic junction of the two peninsulas and the headquarters of the Dutch army in 1942, which collapsed almost immediately, leaving the Australian forces hopelessly exposed. For most of the group, however, the locality was probably memorable for the local dessert: tropical fruit smothered in crushed peanuts, chilli, and cane sugar – a delicacy, we assume, that the POWs never sampled.

As for philanthropy: we visited a privately run orphanage that the Gull Force Association and Rotary now support with donations and in-kind assistance. We brought bags of food and gifts for the children who sat patiently lining the walls of the hall opposite us. They soon erupted into life when given a variety of treasure including balls. One of our group, an octogenarian, played ball with a visually impaired girl. I pondered funding a basketball ring. Others articulated a sense of obligation to ensure this aid program continued.

The following day we visited a village close to where many Australians had been trapped and relentlessly shelled in the last days of their hopeless battle (as I told anyone who cared to listen). It was all very jolly: welcome dances, a communal meal which Gull Force served to the villagers, and the group leader delighting all by playing the ukulele. ‘These are the good days,’ G said to me, ‘when you’re welcomed to their villages.’

This history of cross-cultural connections and friendships, refreshed year on year, is what invests the pilgrimage with its rich layers of memory. These might well be the reason that Ambon pilgrimages continue in the future. The fate of some pilgrimages – and, indeed, of the 23,000 cemeteries and memorials that the CWGC maintains around the world – must surely be in doubt as the decades pass. Even now, something of a hierarchy exists in the CWGC cemeteries. Some are visited by hordes of tourists, others rarely so. A demand-driven model of economics would sit uneasily with remembrance, but the Commonwealth governments that form the CWGC might ultimately choose to privilege those cemeteries that have a high level of usage by visitors.

Beyond that, we do not know how long the communities of the Asia-Pacific region will tolerate these obviously imperial footprints upon their soil. In many places, these have become part of the local landscape, aesthetically appealing green spaces invested with new local meanings over the years. But many are now on prime real estate, as the surrounding cities expand and encroach upon them. Will they all last ‘in perpetuity’, as the CGWC agreements with host governments prescribe?

In the case of Ambon, the cemetery has already endured a sectarian attack. In 1999, Ambon erupted into communal violence, caused by a complex mix of religious tensions and economic and political competition between Christians and Muslims. The violence spread throughout the Moluccas and, by mid-2001, an estimated 4,000 people had died and more than 500,000 had been displaced. The Cross of Sacrifice in the Tan Tui cemetery was another casualty, smashed by Muslim activists. Some years later the CWGC replaced it, but with a less overtly Christian Stone of Remembrance. Few know that this stone was originally designed by that quintessential imperial architect, Edwin Lutyens, and that its inscription, ‘Their name liveth for evermore’, comes from Ecclesiastes. It was recommended by another great imperialist, Rudyard Kipling.

As for the pilgrimages to Ambon: the children of Gull Force veterans are now in their seventies or eighties. Soon they will be unable to cope with the rigours of the long journey, Ambon’s hazardous footpaths, and the enervating humidity. For the grandchildren and great-grandchildren, the cross-generational memory of the war will become attenuated and devoid of emotional power. Who really cares, after all, about the men who fought in the Boer War, let alone Waterloo?

However, the pilgrimage to Ambon might well continue, given that it has become its own site of memory. The philanthropic activities and personal friendships with Ambonese – and the values of cross-cultural understanding and generosity that they represent – do not yet eclipse the rituals of remembrance, but they are a powerful parallel legacy that the descendants of Gull Force will inherit. They might well perpetuate it, even when they know little about why or how the war cemetery at Tan Tui and the Ambon pilgrimage came into being.

Comments (2)

On ANZAC Day 2022, I laid a wreath at the dawn service at Currumbin, where I am a life member due to my service in Vietnam, with Australian Signal Corp, the commemorate the 80th anniversary of the fall of Ambon to the Japanese on 3 February 1942, and the Laha massacre

We must not foirget the other units of the 23rd Brigade, which consist of 2/22 Battalion, Lark Force, who went to Rabaul and also the Toi plantation massacre; and the 2/40th Battalion, Sparrow Force, who went to Timor. This time last year, the Japanese cargo ship Montevideo Maru was found off the Philippines. It was sunk on the night of 1 July 1942 by an American submarine, unaware that it was carrying over 1000 Australian POWs from Lark Force, as well as Dutch and British civilians destained for Haiman. In Roger Maynard's book 'Ambon', dad is mentioned. He was very reluctant to say much, as he was scared - 70 years following the fall of Ambon to the Japanese - that DVA would take away his service pension if he spoke out against the Australian government of the day. Rest in peace, Dad. Lest We Forget.

For instance, the statement referring to a concept of a veteran as a, "...notion of a consolidated and unified collective, and a figurative and metaphorical representation of loyalty, service, citizenship, and nationhood..." is best read as careless hyperbole given the calamity.

"Patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel", as Samuel Johnson wrote, and I am surprised to see it emerge here unchallenged in 2024.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.