James Bradley

What the authors of these three wildly different books share is a gift for creating through language a kind of intimacy of presence, as though they were in the room with you. Emily Wilson’s much-awaited translation of The Iliad (W.W. Norton & Company) is a gorgeous, hefty hardback with substantial authorial commentary that manages to be both scholarly and engaging. The poem is translated into effortless-looking blank verse that reads like music. The Running Grave (Sphere) by Robert Galbraith (aka J.K. Rowling), the seventh novel in the Cormoran Strike crime series and one of the best so far, features Rowling’s gift for the creation of memorable characters and a cracking plot about a toxic religious cult. Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional (Allen & Unwin, reviewed in this issue of ABR) lingers in the reader’s mind, with the haunting grammar of its title, the restrained artistry of its structure, and the elusive way that it explores modes of memory, grief, and regret.

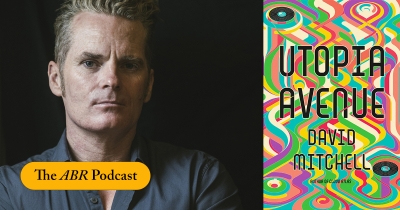

... (read more)In today's episode, author and critic James Bradley speaks to ABR's digital editor Jack Callil about David Mitchell's latest novel Utopia Avenue. Mitchell is perhaps best known for his 2004 work Cloud Atlas, a work of sprawling interconnected narratives. In a similar vein, Utopia Avenue traces the intricate lives of four band members during their ascent to fame during the bustle of the 1960s. Yet as James Bradley details, the book is less concerned with history or music then with its own 'metaphysical game'.

... (read more)I’m always little uneasy about the edge of élitism underlying the policing of language, but I have to confess to a loathing for psychological banalities like ‘closure’ and ‘unconditional love’, most of which are actually worse than meaningless.

... (read more)