Beyond the mundane

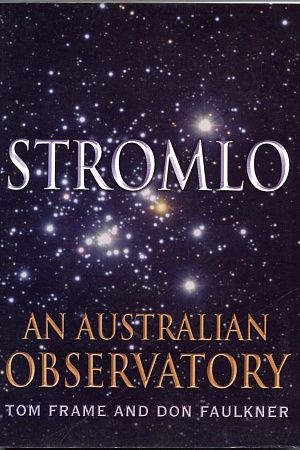

After Netflix’s intriguing sci-fi thriller 3 Body Problem streamed into Australia earlier this year, readers rushed out in droves to buy the book on which the series is based: Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (2008), which was first translated into English in 2014. Most reviews have focused on the philosophical, literary, and cultural aspects of the book – and they are, indeed, fascinating. But the thing that interests me here is the accurate scientific detail that Liu uses to drive the story. Of course, this is sci-fi, so ultimately he presses real concepts into unreal (but imaginative) service. Still, much more physics and maths appear in his book than in the Netflix series, which, according to Tara Kenny’s review in The Monthly (April 2024), ‘offers a welcome workaround’ the science through visual effects. In the book, by contrast, ‘Lengthy passages are spent dutifully explaining physics theories and technological functionality, which is likely to deter readers who haven’t thought about science since they dissected a rat in high-school biology.’

Kenny’s assumption about the likely response of Australian readers to complex scientific ideas is telling – and probably fairly accurate overall, judging by the relatively low number (around ten per cent) of Year Twelve students undertaking advanced mathematics and physics courses. Perhaps this is why in-depth popular science writing is rarely rated as ‘literature’ by our literary gatekeepers. For instance, it rarely makes the shortlists of our non-fiction literary awards, now that the special science categories that existed a decade or two ago have disappeared. When it does, the emphasis is on the social and political consequences of science, rather than on its ideas. Still, ‘hard science fiction’ (a science-oriented subgenre of sci-fi) attracts quite a readership here, as does popular science. In fact, many passages in The Three-Body Problem read like popular physics, including, naturally, an explanation of the eponymous problem, in which the paths of three or more gravitationally interacting bodies can become chaotic, unlike the predictable orbital ellipses of a two-body system such as Earth and Sun.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (2)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.