2017 Arts Highlights of the Year

To celebrate the year’s memorable plays, films, concerts, operas, ballets, and exhibitions, we invited twenty-six critics and arts professionals to nominate some personal favourites.

Robyn Archer

While the original production of Saul (ABR Arts, 3/17), directed by Barrie Kosky, was made in Europe, this version included several Australian singers, a local chorus, and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra. Christopher Purves in the lead role was superb.

Christopher Lowrey as David (top) and Christopher Purves as Saul (in front) in Saul at the 2017 Adelaide Festival (photograph by Tony Lewis)

Christopher Lowrey as David (top) and Christopher Purves as Saul (in front) in Saul at the 2017 Adelaide Festival (photograph by Tony Lewis)

I include David Hockney: Current (NGV) for a number of reasons. While I constantly advocate appropriate support for living artists in all genres, the visual art ‘contemporary’ bandwagon begs interrogation. Hockney said, ‘All art is contemporary, if it’s alive: and if it’s not alive, what’s the point of it?’ I’d argue that there’s as much alive in old stuff as there is in the new – and as much corpsed and pointless in the new as in the old.

Confessing bias (I was the MC and performed in it), I mention The Coming Back Out Ball (Melbourne Town Hall) not for the night itself, which was a moving hoot, but for the three-year project. Tristan is a terrific creator/performer but this work showed his dedication to the social issues facing elderly LGBTIQ people, and showcased the special ability of the arts to bring hard societal material into a joyous and celebratory space.

Ian Dickson

In a strong year for theatre, Lucy Kirkwood’s Chimerica (ABR Arts, 3/17) stood out. Kip Williams’s production matched the scale and sweep of Kirkwood’s enthralling play. Banished from the Opera House, Opera Australia presented two works in concert form. Nicole Car and Étienne Dupuis made an exciting pair of protagonists in Massenet’s Thaïs (ABR Arts, 7/17). Good though the much-heralded Jonas Kaufmann was as the eponymous Parsifal, the performance (ABR Arts 8/17) was dominated by Kwangchul Youn’s Gurnemanz. Best of all was the sound of the Opera Australia Orchestra, finally liberated from underneath the stage of the Joan Sutherland Theatre.

Terence Davies’ biopic of Emily Dickinson, A Quiet Passion (ABR Arts, 6/17) could have been a sombre affair, but Davies and the magnificent Cynthia Nixon found the humour and resilience in the belle of Amherst.

Cynthia Nixon and Joanna Bacon in A Quiet Passion (Palace Films)

Cynthia Nixon and Joanna Bacon in A Quiet Passion (Palace Films)

Rosalind Appleby

I’ve been brooding all year on the metaphors in Dmitry Krymov’s Opus 7 (Perth Festival). The production was a requiem for lives obliterated by the Nazi and Soviet regimes. Puppetry, mime, dance, string, cardboard, and buckets of black paint constructed an immersive journey underpinned by the swagger and pathos of Shostakovich’s music. Lost & Found’s innovative Trouble in Tahiti was similarly provocative, presented so physically and emotionally close to the audience that the work took on an uncomfortable personal resonance. The opera was set in a home in Perth’s affluent western suburbs, where Bernstein’s critique of consumerism and silver screens couldn’t have been clearer to the audience watching with voyeuristic fascination from the patio. In contrast, the rippling energy of WA Opera’s The Merry Widow was sheer fun. A young, versatile cast premièred Graham Murphy’s beautiful, dance-infused production where every act was a party fizzing with romance and comedy.

Harry Windsor

The best local features I saw this year were comedies, not a genre we do well often. But Pork Pie, a remake of Kiwi classic Goodbye Pork Pie (1981), directed by the son of the original film’s director, and Ali’s Wedding, directed by tyro Jeffrey Walker, were confident exceptions, deftly made charmers bursting with colour and a very Antipodean strain of self-importance-busting humour. In terms of international fare, the most affecting film I saw was Katell Quillévéré’s Heal the Living (Réparer les vivants). Set in Paris, it’s the story of a heart transplant seen from every angle: from the point of view of the donor and his grieving parents, the recipient and her frightened sons, and the hospital staff who trundle between them. It features the scene of the year, in which three teenage boys go surfing: a hypnotic symphony of music and image that rousingly celebrates a life being lived joyously, shortly before it’s snuffed out.

Heal the Living (Playtime)

Heal the Living (Playtime)

Des Cowley

There were many memorable performances by jazz and improvising musicians throughout 2017. Two that stood out incorporated strong visual and theatrical elements. Pianist and composer Erik Griswold partnered with the Australian Art Orchestra and visiting musicians from China and Singapore to perform his extended suite Water Pushes Sand at Jazzlab. The dramatic work, which features both traditional Sichuan melodies and jazz improvisation, was highlighted by Zheng Sheng Li’s startling ‘face changing’ dance. Composer and multi-instrumentalist Adam Simmons’s The Usefulness of Art (ABR Arts, 8/17), performed by a large ensemble at fortyfivedownstairs, similarly incorporated theatrical costume and design to heighten the power of this impassioned music. The Melbourne International Jazz Festival (ABR Arts, 6/17) was distinguished by the first Australian appearance by pianist Carla Bley, who, aged eighty-one, demonstrated why she is considered one of jazz’s finest composers.

Adam Simmonds and his ensemble perform The Usefulness of Art at fortyfivedownstairs (photograph by Sarah Walker)

Adam Simmonds and his ensemble perform The Usefulness of Art at fortyfivedownstairs (photograph by Sarah Walker)

In a year that included many films, I continue to be haunted by Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless, an excoriating vision of contemporary Russia. Raoul Peck’s powerful documentary on James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro (ABR Arts, 9/17), confirmed that the writer’s words remain as powerful today as when first published.

Anwen Crawford

Robin Campillo’s BPM – an urgent recreation of AIDS activism in Paris during the early 1990s – felt resonant and still timely. BPM won the Grand Prix and the Queer Palm at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, but seemed to fly under the radar at the Melbourne International Film Festival. Other MIFF highlights included Maud Alpi’s Still Life and Sergei Loznitsa’s Austerlitz, two experimental documentaries that investigate how we confront – or fail to confront – killing on an industrial scale. The former film is set inside a slaughterhouse; the latter takes Holocaust tourism as its subject. On a lighter note, Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen was a cut above the usual coming-of-age dramedy. Kelly Reichardt’s acutely observed Certain Women and Barry Jenkins’s exquisite Moonlight (ABR Arts, 1/17) both reached local screens at last; two gifted directors, two contemporary masterpieces.

Alex Hibbert and Mahershala Ali in Moonlight (Roadshow Films, photograph by David Bornfriend)

Alex Hibbert and Mahershala Ali in Moonlight (Roadshow Films, photograph by David Bornfriend)

Andrew Ford

I didn’t expect much from Myuran Sukumaran: Another Day in Paradise (Sydney Festival), but was deeply moved by the evidence of his burgeoning talent. He was a real artist – obsessed and hard-working. Had he not been executed, he might have become a very good one. Also in the festival, Mary Finsterer’s Biographica was full of fine music. The actor protagonist was distracting – shouting to be heard above the singers of Sydney Chamber Opera and players of Ensemble Offspring – so I blotted him out. As a result, I can’t tell you exactly what the opera was about, but it sounded magnificent.

At WOMADelaide, The Manganiyar Classroom called to me across a crowded park. I knew nothing about it in advance, but couldn’t move until it was over. I live in the country with a seven-year-old daughter, so don’t get too much. Together, we saw Disney’s Moana at the Bowral Empire. It’s rather good. To get the full effect, watch it in a cinema next to a child trembling with excitement.

John Allison

Coincidentally, Austria provided my two most thrilling opera experiences in 2017. The Landestheater Linz’s staging of Hindemith’s Die Harmonie der Welt vindicated a great rarity by this now sadly unfashionable composer. The hit of the Salzburg Festival was the artist–director William Kentridge’s staging of Wozzeck, an unusually satisfying realisation of Berg’s masterpiece. Several of the best concerts in Britain this year have often come courtesy of Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, the new music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Her free-thinking flair makes her the most exciting thing to have happened to the CBSO since Simon Rattle.

The cast of Wozzeck (Salzburger Festspiele, photograph by Ruth Walz)

The cast of Wozzeck (Salzburger Festspiele, photograph by Ruth Walz)

While not wanting to appear unserious about my work, I cheerfully admit to planning reviewing trips around art exhibitions. My most memorable show away from this year’s international blockbusters was at Bucharest’s National Gallery, where its brilliantly curated exploration of Romanian socialist realist art – Art for the People? 1948–1965 – proved fascinating to someone interested in Balkan culture.

Michael Halliwell

Pride of place goes to Brett Dean’s Hamlet (ABR Arts, 6/17), which premièred at Glyndebourne with an all-Australian creative team. A taut, musically mesmerising version of this highly challenging play makes it one of the most significant new operas in recent years. For my second choice I conflate two recent London productions: Girl from the North Country and Woyzeck in Winter (ABR Arts, 9/17). The first incorporates lesser-known songs from Bob Dylan into a searing melodrama by Conor McPherson, while Woyzeck, adapted and directed by Conall Morrison, conflates the play with Schubert’s Winterreise. Both extend the boundaries of the so-called ‘jukebox musical’, fusing Steinbeck with Brecht.

Jacques Imbrailo, John Tomlinson and Allan Clayton in Hamlet at the 2017 Glyndebourne Festival Opera (photograph by Richard Hubert Smith)

Jacques Imbrailo, John Tomlinson and Allan Clayton in Hamlet at the 2017 Glyndebourne Festival Opera (photograph by Richard Hubert Smith)

Finally, a Sydney production (Hayes Theatre Co) of Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins, directed by Dean Bryant, gives a welcome outing to this neglected work. A cast of young singers led by David Campbell provided an evening of unfailing energy and vivid characterisation. The performance I saw was coloured by the Las Vegas shootings a few days before. America and its guns – nothing changes!

Lee Christofis

Men in a state of meltdown dominate my two top dance shows this year: The Winter’s Tale, from London’s Royal Ballet, at QPAC (ABR Arts, 7/17); and Cockfight, by Joshua Thomson, Gavin Webber, and tiny Gold Coast company The Farm, at Dance Massive, Melbourne. Created by British choreographer Christopher Wheeldon and composer Joby Talbot, Winter’s Tale is the best dance drama to appear here in decades. Edward Watson, as the deranged Leontes, King of Sicilia, led a superlative cast in a strange story of deranged jealousy, brutal injustice, and gentle redemption. Cockfight is a hyper-kinetic contact improvisation work about a dysfunctional manager (Webber), who taunts and nearly kills a younger, smarter job applicant (Thomson) in a battle of wit and will. Seduction, lies, threats, and rage take dangerous flight across a sterile office. Each object, especially the phone cord, becomes a weapon as they fight for supremacy. Too brutal to watch, too funny to miss, this was Aussie Grand Guignol at its best.

Francesca Hayward and Steven McRae in The Royal Ballet's The Winter's Tale (photograph by Stewart Tyrell)

Francesca Hayward and Steven McRae in The Royal Ballet's The Winter's Tale (photograph by Stewart Tyrell)

Will Yeoman

Beyond Caravaggio at London’s National Gallery was impressive but also slightly oppressive. Stepping from this gloomy world into the blazing Australian and southern French sunshine of the Australia’s Impressionists (National Gallery) showing at the same time made a strong impression.

Back in Perth, the highlight of PIAF’s Beethoven and Beyond, with the LA-based Calder Quartet, was Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet, with local clarinettist Ashley Smith: a performance characterised by subtle and exquisite balance and phrasing, with Smith’s floating, plangent tone and deeply expressive playing matched by the Calder’s unerring instinct for light and shade. I enjoyed Terence Davies’ masterful biopic of Emily Dickinson, A Quiet Passion, Lost and Found’s innovative, witty production of Leonard Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti, mounted in a private home, and a sublime Mahler Fifth from WASO under chief conductor Asher Fisch, who, it appears, can do no wrong.

Morag Fraser

I Am Not Your Negro is the work of art to heed in 2017. Directed by Raoul Peck and narrated by Samuel L. Jackson, the film is artfully compiled – a model documentary. But it is James Baldwin – that mobile face and inimitable voice – who is the compelling, prophetic presence, as provocative and unanswerable now as he was when he uttered these confronting words: ‘The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. And it’s not a pretty picture.’

I am Not Your Negro (Madman Entertainment)

I am Not Your Negro (Madman Entertainment)

Baltimore offers guided tours of The Wire’s bleak territory, but its Museum of Art revealed another side of this intriguing, evolving city when it mounted a grand comparative exhibition of works by Henri Matisse and Richard Diebenkorn (many of the Matisses came into the Museum’s collection courtesy of Baltimore’s redoubtable and philanthropic Cone Sisters). The art was breathtaking, and the documentation – encompassing both artists’ lifelong shuttle between representation and abstraction, and the subtlety of Matisse’s influence on the Californian – a curatorial triumph.

Zoltán Szabó

Two highlights came from the same genre: opera, presented by different companies. Neither work was staged, thus the artistic impression was entirely musical. In June, Pelléas et Mélisande (ABR Arts, 6/17) by Claude Debussy was performed in Sydney for the first time since 1998. At the helm of the SSO, Charles Dutoit led a mostly native French-speaking cast with restrained passion and boundless sensitivity. Debussy’s opera was much influenced by Wagner’s music dramas, so it was fitting that the latter composer’s Parsifal made a long-awaited return to the Opera House. Pinchas Steinberg conducted the excellent cast, where primus inter pares Kwangchul Youn’s mesmerising performance stood out in the role of Gurnemanz as much as Jonas Kaufmann’s singing of the eponymous hero.

Pelléas et Mélisande (Sydney Symphony Orchestra, photograph by Darren Leigh Roberts)

Pelléas et Mélisande (Sydney Symphony Orchestra, photograph by Darren Leigh Roberts)

A final memorable experience came from Tokyo, where András Schiff (who will visit Australia in October 2018) offered a thought-provoking and terrific juxtaposition of the penultimate sonatas of Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven (ABR Arts, 3/17).

Tony Grybowski

With the closure of the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Opera Australia grasped the opportunity to present opera in different venues across Sydney. One of these experiences was a concert presentation of Wagner’s Parsifal. It was a treat to see the Opera Australia Orchestra (usually hidden in the pit) shine on the stage of the Concert Hall.

Every five years the German town of Kassel is transformed into a magnet for lovers of contemporary art. At documenta 14, founded after World War II as a way to enable artists to join and express a voice to help rebuild a nation, it is exciting to see Australian artists on an international stage. This year, three Australians were represented: Gordon Hookey, Dale Harding, and Bonita Ely, all presenting large scale work that drew on narratives involving displacement, ecological destruction, and oral traditions of Aboriginal communities.

Bangarra Dance Theatre’s major 2017 production, Bennelong, by Stephen Page took the company to a new level – compelling and captivating with beautiful movement, dance, design, and a wonderful score by Steve Francis.

Beau Dean Riley Smith (centre) in Bennelong (Bangarra Dance Theatre, photograph by Daniel Boud)

Beau Dean Riley Smith (centre) in Bennelong (Bangarra Dance Theatre, photograph by Daniel Boud)

Susan Lever

After Nina Stemme’s and Stuart Skelton’s heart-stopping performance of Tristan und Isolde with the TSO in Hobart (ABR Arts, 11/16), concert opera performances were again high points of this year. Opera Australia’s Parsifal was glorious, but OA’s concert version of Thaïs was delightful in a different way, with the energetic young singers Nicole Car and Étienne Depuis clearly enjoying singing Massenet’s melodic music together in the warm atmosphere of the Sydney Town Hall.

I saw two exceptional theatre productions: first, Bell Shakespeare’s thrilling interpretation of Richard 3 (ABR Arts, 3/17), with Kate Mulvany; second, New Theatre’s revival of Dorothy Hewett’s The Chapel Perilous. The young performers of this play, especially Julia Christensen in the lead, found both the poetry and political power in Hewett’s classic. It was an intelligent and engaging production. If only more people had known about it.

Tim Byrne

Apart from Malthouse Theatre’s sensitive but radical production of Michael Gow’s Away (ABR Arts, 2/17) and some magnificent local choreography in Australian Ballet’s Symphony in C, this year’s best work came from sublime interpretations of major international work. Kate Mulvany was so poised and savage, so damaged and damaging as Richard III for Bell Shakespeare that she seemed born for the role. It was the most impressive performance of the year.

MTC’s production of Annie Baker’s John (ABR Arts, 2/17) was perfect; complex and meticulous, it used its cultural specificity to universal effect, and contained riveting performances from Helen Morse and Melita Jurišić. Sarah Goodes has quickly established herself as one of the country’s finest directors.

Johnny Carr, Helen Morse, and Melita Jurišić in Melbourne Theatre Company's John (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Johnny Carr, Helen Morse, and Melita Jurišić in Melbourne Theatre Company's John (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Gary Abrahams’s extraordinary rendition of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America at fortyfivedownstairs, with Morse joining a stellar ensemble, was so compassionate, so articulate, it seemed like a totally contemporary play. Galvanising and angry, it was theatre as a monumental political act.

Barney Zwartz

Two near-perfect performances: one an opera, one by an opera singer led 2017. Listening to brilliant bass Ferruccio Furlanetto singing Russian songs by Rachmaninov and Mussorgsky in the glorious acoustic of the Melbourne Recital Centre in October was like watching a Ferrari in a go-kart rink: far too much power for the arena, with a purring richness that was seldom extended, but the interest was in the incredible delicacy and control, the fine tunings and shadings, the intimacy, the emotional conviction. Opera Australia’s concert performance of Parsifal, with superstars Jonas Kaufman and Michelle deYoung, and another massive bass in Kwangchul Youn, was mesmerising. Honourable mentions go to Victorian Opera’s beautifully crafted and performed production of Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen (ABR Arts, 6/17), Opera Australia’s ambitious and deeply satisfying account of Szymanowski’s King Roger (ABR Arts, 1/17), and the MSO’s concert performance of Massenet’s lyrical opera Thaïs (ABR Arts, 8/17), with Erin Wall in the title role.

Cunning Little Vixen (Victorian Opera, photograph by Jeff Busby)

Cunning Little Vixen (Victorian Opera, photograph by Jeff Busby)

Brian McFarlane

It’s a large claim, but I suspect that Simon Phillips’s production of Macbeth (ABR Arts, 6/17) is the best I have ever seen. In a contemporary military setting, it never struck a jarring note as it melded two eras. Without interval, it made remorseless the rise and tragic fall of its eponym.

So many films clamour for mention that it is hard to limit my choice to three. In the part-Australian feature, Lion (ABR Arts, 1/17) first-time director Garth Davis showed himself admirably versatile as well as compassionate in dealing first with the child’s agonising loss and then in rendering the decent feelings of the foster parents without descending into sentimentality. Loving, the UK/US drama of interracial marriage and its ensuing legal struggles, was note-perfect in its retelling of a poignant, ultimately triumphant, real-life story. As for ‘real-life’, Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk is a stunning recreation of this ‘finest hour’ in all its chaos and courage.

Nicole Kidman, David Wenham, and Sunny Pawar in Lion (Transmission Films)

Nicole Kidman, David Wenham, and Sunny Pawar in Lion (Transmission Films)

Peter Rose

Nothing quite matched Pierre-Laurent Aimard’s phenomenal 2016 Messiaen recital (absurdly overlooked in the Helpmann Awards) or the TSO’s Tristan und Isolde concert, with Stuart Skelton and Nina Stemme, but there were some memorable performances. Two Hamlets I saw in June couldn’t have been more different: Brett Dean’s brilliant new opera at Glyndebourne, with an exceptional cast of singers, many of whom will return for the Adelaide Festival. Then came Robert Icke’s version of the play, with Andrew Scott’s searching, mystified prince cogitating his way through the soliloquys.

I relished Kip Williams’s revival of Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine (ABR Arts, 7/17), brilliantly mounted, hilarious in places, and featuring a memorable performance from Heather Mitchell.

Heather Mitchell and Josh McConville in Sydney Theatre Company’s Cloud Nine (photograph by Daniel Boud)

Heather Mitchell and Josh McConville in Sydney Theatre Company’s Cloud Nine (photograph by Daniel Boud)

And films? Sally Hawkins deserves an Oscar for her role as the eccentric painter Maud Lewis in Aisling Walsh’s underrated Maudie: physical acting at its best. James Baldwin, in the superbly edited documentary I Am Not Your Negro, makes present-day orators look like pygmies. Baldwin’s message, fifty years on, remains incensingly topical.

Leo Schofield

At the Edinburgh International Festival, I heard an unforgettable concert performance of Die Walküre, with a superb line-up of singers, including Bryn Terfel, Christine Goerke, Simon O’Neill, Amber Wagner, and Karen Cargill, plus the Royal Scottish Orchestra under Andrew Davis. A week or so later, Opera Australia came up with a magnificent concert Parsifal, with Jonas Kaufmann, Michelle deYoung, Michael Honeyman, Warwick Fyfe, the mighty Korean bass Kwangchul Youn, and the Opera orchestra and chorus under Pinchas Steinberg. If anything, this was musically finer than the Edinburgh performance, the half dozen Sydney Flower Maidens easily outsinging their eight Scottish Valkyrie sisters.

Michael Honeyman, Kwangchul Youn, Jonas Kaufmann, Pinchas Steinberg, and Michelle DeYoung in Opera Australia's Parsifal (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Michael Honeyman, Kwangchul Youn, Jonas Kaufmann, Pinchas Steinberg, and Michelle DeYoung in Opera Australia's Parsifal (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Other unforgettable events were the Brisbane season of the Royal Ballet and the open-air gala in Cairns; Daniil Trifonov’s dazzling solo recital at Angel Place; the ACO’s concert with the spotlight on Sätü Vanska, Timo-Veikko Valve, and Glenn Christensen; the Adelaide Festival trifecta of Glyndebourne’s smashing Saul, the third and by far the finest incarnation of The Secret River, and Lars Eidinger’s in your face Richard III. The once-great Adelaide Festival had finally its mojo back.

Diana Simmonds

In March I wrote, ‘Three of the most memorable musical experiences of my life have happened in Adelaide: Elke Neidhardt’s production of Wagner’s Ring, the State Opera of South Australia’s Cloudstreet, and now the Armfield–Healy Adelaide Festival’s offering of Barrie Kosky’s Saul.’ Meanwhile, in Sydney, independent theatre has been spectacular, with Siren Theatre’s The Trouble With Harry, and Dorothy Hewett’s The Chapel Perilous. Musical theatre hub Hayes Theatre Co thrilled with Paul Capsis in Cabaret, Virginia Gay in Calamity Jane, and Emma Matthews in Melba. The rise of Red Line at the Old Fitz continued; outstanding were Doubt: A Parable, the beautiful 4:48 Psychosis, a new work from Louis Nowra: This Much Is True (ABR Arts, 7/17), and a breakout performance from Gabrielle Scawthorn in The Village Bike. Women dominated the landscape: Kate Mulvany as Richard 3, Genevieve Lemon in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Helen Thomson in Hir, and Heather Mitchell in Cloud Nine.

Ben Brooker

Like almost everyone who saw it, I was blown away by Glyndebourne Festival Opera’s Saul, the Barrie Kosky-directed centrepiece of this year’s Adelaide Festival. The return of Adelaide’s prodigal son did not disappoint, proving a feast for all the senses. Also in this year’s Festival was Wot? No Fish!! (ABR Arts, 3/17), as intimate as Saul was epic. Based around sketches made by his great-uncle, a working-class East End Jew, British writer–performer Danny Braverman’s simply and sparklingly adumbrated family history moved me deeply. Mr Burns, a co-production by STCSA and Belvoir, brought American playwright Anne Washburn’s 2012 post-apocalyptic play, ostensibly about The Simpsons, to vivid life in a production directed by Imara Savage. I must mention Lucy Kirkwood, the young British playwright whose uncommonly ambitious dramas The Children and Chimerica I was fortunate enough to see in London and Sydney respectively. I’m excited about MTC’s production of The Children next year.

Danny Braverman in Wot? No Fish!! at the 2017 Adelaide Festival (photograph by Tony Lewis)

Danny Braverman in Wot? No Fish!! at the 2017 Adelaide Festival (photograph by Tony Lewis)

Christopher Menz

Fred Williams in the You Yangs (ABR Arts, 10/17), at the Geelong Gallery, was a model exhibition of one of Australia’s greatest artists. A judicious and thoughtfully displayed selection of just over sixty works – oil paintings, prints, gouaches – highlighted his best work from the 1960s.

Opera Australia’s concert performance of Parsifal, with a superb cast under the impressive baton of Pinchas Steinberg, was electrifying and showed how well Wagner’s music dramas present in the concert hall. Angela Hewitt (ABR Arts, 5/17) was in dazzling form during her Musica Viva tour, with intelligent, balanced programs including works by Scarlatti, Ravel, and Chabrier, as well as the obligatory Bach: this time, selected partitas.

Angela Hewitt (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Angela Hewitt (photograph by Keith Saunders)

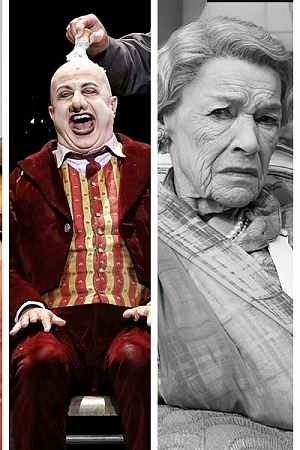

Michael Shmith

For various reasons, Melbourne Lyric Opera’s production of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppea) was one of my highlights of the year. As I wrote at the time, ‘the work itself is hard-edged – in soap-opera terms, more pumice stone than Palmolive. Accordingly, it duly received a swift and sinewy performance, keenly driven by [artistic director] Pat Miller, who conducted from the keyboard.’

Damian Whiteley in Lyric Opera of Melbourne's The Coronation of Poppea (photography by Sara Walker)

Damian Whiteley in Lyric Opera of Melbourne's The Coronation of Poppea (photography by Sara Walker)

The National Gallery of Victoria’s monumental exhibition of almost 180 works by Katsushika Hokusai elevated him far above his self-deprecatory summary, ‘Old man mad about drawing’. In fact, the exhibition made one as eternally grateful to the NGV’s Felton Bequest as it did for the eternally fecund genius of Hokusai. Thanks to Alfred Felton (old man mad about art?), a woodblock print of Hokusai’s most famous work, The great wave off Kanagawa 1830–34 has been in the Gallery’s possession for 108 years.

Kim Williams

Whilst there have been many pleasures this year in music, film, and opera, there were three pieces of standout Australian theatre, all conceptually large and all produced by the STC. Lucy Kirkwood’s Chimerica and Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine were both directed by Kip Williams. The other was a memorable revival of Neil Armfield’s production of Andrew Bovell’s The Secret River at the Adelaide Festival. The Secret River and Chimerica had substantial casts, all too rare on the Australian mainstage in today’s straitened times for the arts. Both were cinematic in their sweep, superbly acted and designed, and hauntingly dramatic. Cloud Nine, one of Churchill’s greatest works, is another reminder as to why she is one of the theatre’s true creative imaginations and a leader. Each play is relevant to today’s polemics on human rights, diversity, and reconciliation. We have much reason to be thankful to Williams, Armfield, their casts and creative teams for making theatre that matters.

Another major personal moment was the Sam Mendes’s London production of Jez Butterworth’s The Ferryman – a cast of twenty-one in an intimate but sweeping piece which was emotionally and politically shattering.

Chimerica (Sydney Theatre Company, photograph by Brett Boardman)

Chimerica (Sydney Theatre Company, photograph by Brett Boardman)

Andrea Goldsmith

Thirty years ago I saw Anthony Sher play Richard III. It was a memorable portrayal, one which became the Richard for me. When I read that Bell Shakespeare had cast a woman in the role, I was, frankly, appalled, dismissing it as part of the current trend of having female actors play Shakespeare’s major male roles. How wrong I was. It was a superb production. Kate Mulvany’s Richard was utterly compelling and showed him as wily and evil as well as humorous and seductive. Mulvany played the king in a way that revealed nuances of his character I’d never seen before. One of Bell Shakespeare’s best.

Kate Mulvany in Richard 3 (Bell Shakespeare, photograph by Prudence Upton)

Kate Mulvany in Richard 3 (Bell Shakespeare, photograph by Prudence Upton)

It’s a risky business revisiting old loves. In April, Patti Smith, performed the songs from Horses, her best-known album, originally released in 1975. By the end of the first song, I was on my feet, seized by the familiar music and Smith’s irresistible performance, and so I remained until the music died away. Patti Smith is seventy, she’s still creating, and she is magnificent. At home I dusted off my LP and prolonged the pleasure.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.