Books of the Year 2023

Kerryn Goldsworthy

What the authors of these three wildly different books share is a gift for creating through language a kind of intimacy of presence, as though they were in the room with you. Emily Wilson’s much-awaited translation of The Iliad (W.W. Norton & Company) is a gorgeous, hefty hardback with substantial authorial commentary that manages to be both scholarly and engaging. The poem is translated into effortless-looking blank verse that reads like music. The Running Grave (Sphere) by Robert Galbraith (aka J.K. Rowling), the seventh novel in the Cormoran Strike crime series and one of the best so far, features Rowling’s gift for the creation of memorable characters and a cracking plot about a toxic religious cult. Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional (Allen & Unwin, reviewed in this issue of ABR) lingers in the reader’s mind, with the haunting grammar of its title, the restrained artistry of its structure, and the elusive way that it explores modes of memory, grief, and regret.

Paul Giles

The major publishing event of the year in Australian literature was Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy (Giramondo, 4/23), a deeply impressive but long and complex novel that resists political simplifications and demands more than one reading. But the novel I enjoyed most was Richard Ford’s Be Mine (Bloomsbury, 8/23), with Ford’s alter ego Frank Bascombe painting a sardonically evocative picture of contemporary American landscapes as his own physical body starts to crumble. Commenting on the feel-good vibe of his health clinic, Bascombe observes how they promote the idea that ‘anyone and everyone can walk in, sign up for a round of chemo or a cardiac catheterization and be back in the Cities for dinner’. In literary criticism, Barron Field in New South Wales: The poetics of Terra Nullius, by Thomas H. Ford and Justin Clemens (Melbourne University Press, 7/23), offered a quirky but well-informed and perceptive account of the origins of Australian romanticism.

Zora Simic

My major reading project was an Annie Ernaux binge, and it continues, since her Nobel Prize has resulted in a steady stream of new translations. Two memoirs I had great hopes for exceeded my own high expectations: poet Amy Key’s Arrangements in Blue: Notes on loving and making a life (Jonathan Cape), the title and shape of which is inspired by Joni Mitchell’s classic album Blue; and Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You (Simon & Schuster) by Lucinda Williams. Pairing them highlights what they have in common, though Key is English and in her forties, while Williams, one of the greatest living American singer-songwriters, turned seventy not long ago. Both are poets who sit with the truth, no sugar-coating. Fiction-wise, my standout was Bryan Washington’s Family Meal (Atlantic) – he hooks me instantly each time. The year is not over though, and I’m excited by new fiction from Tony Birch, Melissa Lucashenko, and Christos Tsiolkas.

Frances Wilson

Two books about marriage are my best reads of the year. Marriage was George Eliot’s abiding fascination, but she lived, for twenty-four years, with a man she could not marry because he was married to a woman he could not divorce. In The Marriage Question: George Eliot’s double life (Allen Lane), Clare Carlisle reflects on the gamble of yoking your happiness to ‘the open-endedness of another human being’. Anna Funder’s Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s invisible life (Hamish Hamilton, 7/23) is about doublethink rather than double lives. Applying Orwell’s own phrase, from Nineteen Eighty-Four, to his treatment of his first wife, Eileen, Funder explores the contradictions at the heart of his beliefs about equality. Eileen, never mentioned by name in his letters or books, typed and edited his manuscripts, humanised his writing, influenced his style, sorted out the septic tank, and put up with his infidelities until, aged thirty-nine, she died of the exhaustion of being married to Orwell. She was not, he remembered, ‘a bad old stick’.

Bain Attwood

The most important book I read this year – Enzo Traverso’s Singular Pasts: The ‘I’ in historiography, translated by Adam Schoene (Columbia University Press) – ably delineates the various roots of a major shift in historical practice that is seeing scholarly accounts of the past increasingly written in the first person, and provides a measured critique of the results of this subjectivist turn. He would no doubt welcome the most exceptional history I have read this year: Graeme Davison’s My Grandfather’s Clock: Four centuries of a British-Australian family (Miegunyah Press, 11/23). This brilliantly conceived, beautifully written, and eminently wise book addresses fundamental existential questions – who am I, where do I come from, what familial and generational ties connect me to the past – without slipping into presentism and narcissism as Davison retains an analytical spirit and reveals the historical relationship between the collective and the individual, the particular and the universal, the ‘we’ and the ‘I’.

Philip Mead

Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy is a huge novel, more than 700 pages. There has never been another Australian novel like it. It is a huge reservoir of story about the lives of the northern Australian residents of Praiseworthy, including the crazy Aboriginal entrepreneur Cause Man Steel (also known as Widespread and Planet) and his wife, Dance, and their two sons, the self-harming Aboriginal Sovereignty and the little fascist Tommyhawk. There are huge waves of humour: widespread plans to survive the Anthropocene by building a global transport conglomerate using millions of feral donkeys – an idea Cause Man Steel got from watching the Discovery Channel. With her Sino-Aboriginal heritage, Dance wonders, movingly, about the stories that battle for precedence in a soul and its homeland. It is also a huge world of ferocious satire and critique of the racist stupidities of governments and their interventions in Aboriginal people’s lives. The wonderful thing about this novel is its huge difference of language and imagination. It is hard to see how it will be assimilated into Australian writing. And that’s its great value.

Stuart Kells

This year was a great one for ‘books about books’ and especially for books about William Shakespeare, given that 2023 is the 400th anniversary of the First Folio, the second collected edition of his plays (often incorrectly referred to as the first collected edition). For me, highlights included Judi Dench’s disarming Shakespeare: The man who pays the rent (Michael Joseph), Farah Karim-Cooper’s intriguing The Great White Bard: Shakespeare, race and the future of his legacy (Simon & Schuster), and Chris Laoutaris’s illuminating Shakespeare’s Book: The intertwined lives behind the First Folio (William Collins). There were also some important reissues and new editions to mark the anniversary. In the wider field of bibliomania, we saw Sarah Ogilvie’s excellent The Dictionary People: The unsung heroes who created the Oxford English Dictionary (Chatto & Windus, 11/23) and a sumptuous new offering from Edward Brooke-Hitching: Love: A curious history (Simon & Schuster). We are in a golden moment for books about book-making and bibliography.

Joel Deane

The Wren, The Wren (Jonathan Cape, 11/23), Anne Enright’s eighth novel, is effortlessly virtuosic. It nails the first-person voices of three generations of a damaged Irish family – a famous poet, his daughter and his granddaughter. It includes Seamus Heaney-like poetry written by the poet-patriarch, Phil. And it tells a multi-layered, multi-generational story about how Carmel and Nell, the women Phil abandoned, come to terms with the long shadow of familial betrayal. It is a brilliantly written book that doesn’t feel the need to show off. In poetry, I have found solace in Emily Wilson’s vivacious translation of The Iliad. In non-fiction, I’m enjoying Wolfram Eilenberger’s The Visionaries: Arendt, Beauvoir, Rand, Weil and the salvation of philosophy (Allen Lane) – a German take on how the traumas of the 1930s shaped Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Ayn Rand, and Simone Weil.

Jennifer Mills

In a year of troubled reckonings with colonisation, it is stories of justice and struggle that have kept me going. No one else could write about sovereignty and survival the way that Alexis Wright has in Praiseworthy, a magnificent work of politics and imagination. Bookending the year, Melissa Lucashenko’s Edenglassie (UQP, 10/23) is both a ripper riff on the historical genre and a brilliant manual for decolonisation in action – I’ll never see Magandjin the same way again. In between, I was delighted and horrified in equal measure by R.F. Kuang’s page-turning publishing industry satire, Yellowface (William Morrow), and stunned by the audacity of Pip Adam’s abolitionist space opera, Audition (Giramondo, 8/23).

Patrick Mullins

Biographies have supplied some of my best reading hours this year. Walter Marsh’s account of a lean and hungry Rupert Murdoch, in Young Rupert: The making of the Murdoch empire (Scribe, 8/23), was a fresh and timely counterpoint to the wizened and wily figure who this year ‘retired’ from News Corp. By Marsh’s account, I’d guess Murdoch’s dark appetites are nonetheless still unsated. Ryan Cropp’s thoughtful life of Donald Horne, in Donald Horne: A life in the lucky country (Black Inc., 10/23), charted the restless and provocative habits of his subject with care and elegance, and animated decades of faded news and current affairs with colour and poise. Kate Fullagar’s Bennelong & Phillip: A history unravelled (Simon & Schuster), meanwhile, used an inventive structure and humanistic care to cast her subjects in new light: not as paragons of a European enlightenment or doomed bit players, but as men wrestling with circumstance and culture, taking uncertain steps in uncertain worlds, towards futures they could not see or know.

Felicity Plunkett

Poet Terrance Hayes’s Watch Your Language: Visual and literary reflections on a century of American poetry (Penguin) starts with Toni Morrison’s words: ‘I want to draw a map … of a critical geography and use that map to open… space for discovery, intellectual adventure, and close exploration’. Hayes’s buzzy, inviting map locates illustrated micro-reviews alongside quizzes, biographical slivers, and a ‘bookbioboardgame’. Vaulting between questions, it explores his decades reading and (brilliantly) writing poetry, each ‘mostly a matter of keeping an eye on your thinking, of bearing witness, of keeping record’. This exhilarating catalogue of homage and reflection highlights poets excluded from racist and sexist canons, tenderly witnessing an expansive poetic treasury. The Book of (More) Delights (Coronet) comprises micro-essays by poet Ross Gay about delight, written as a practice of attention and sustenance. Gay parses light and shadow, something Amanda Lohrey’s virtuosic The Conversion (Text, 11/23) does in very different ways.

Tony Hughes-D’Aeth

Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy was a reminder, in case we needed it, of what she means to the Australian literary landscape. It is a book that modulates effortlessly through competing cosmologies. As much as anything, I love the earthiness of Wright’s world, and the way she weaves a poetry out of the tics and obsessions of her all-too-human heroes. In a rather different key, I was taken by Nicholas Jose’s novel about East Timorese independence, The Idealist (Giramondo, 11/23). A sophisticated and artfully restrained espionage thriller, it also manages to be a portrait of a certain coming-of-age in Australian political life. Finally, and though I cannot claim complete impartiality, Graham Akhurst’s Indigenous Bildungsroman Borderland (UWAP) is a novel that has stuck with me since I first encountered it in an early draft. Its story has an infectious verve, even as it speaks to areas of experience – particularly those of urban Indigenous young men – that have not quite had the attention they deserve.

Penny Russell

Outstanding books by Australian historians have come thick and fast this year. Uniting zest for narrative with immense research and hard-hitting analysis, Alecia Simmonds’s Courting: An intimate history of love and the law (La Trobe University Press) will transform your understanding of both love and law. Hannah Forsyth’s Virtue Capitalists: The rise and fall of the professional class in the Anglophone world, 1870–2008 (Cambridge University Press) is a riveting, iconoclastic account of the problematic idea of ‘virtue’ as the founding principle of the professions, and its beleaguered status today. Graeme Davison’s family history, My Grandfather’s Clock, entwines sentiment, reflection, and research in a narrative that enchants and enlightens. Alexandra Roginski’s Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World: Popular phrenology in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand (Cambridge University Press) is a rich, enthralling account of the popular science of phrenology and its shadowy practitioners. Great writing is a feature of all four books, but they show that history, at its best, does more than tell a good story. Tying Australia’s history to broader developments in law, science, and industrial and late capitalism, they shed analytic light on some of the knottiest issues of the present day.

Emma Shortis

It is difficult to describe the plot of Pip Adam’s Audition without sounding as if you’ve lost the plot yourself. Three giants, hurtling through space, must keep talking in order to both stop growing and keep their ship running. It is a relentless, captivating read. Leaping disjointedly through time and space, Audition captures the very real and very 2023 feeling that nothing quite makes sense and that yet everything is, somehow, connected. Reading it alongside Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger: A trip into the mirror world (Allen Lane, 11/23) was a surreal experience. Klein is, as always, singular in her ability to capture and explain our current moment. Likewise, Antony Loewenstein’s The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel exports the technology of occupation to the world (Verso) is a devastating analysis of Israel’s military-industrial complex and its connections with the world. All three explain our nightmares and, more importantly, offer us ways out.

Peter Rose

First, the handsome new edition of Franz Kafka’s The Diaries (Schocken Books). What a service translator Ross Benjamin has performed for devotees of Kafka, after the priggish intrusions of Max Brod. ‘Never again psychology!’ At least, never again the psychology of the self-serving literary executor. He restores Kafka to us: witty, preternaturally lucid, more complex than ever. Shirley Hazzard: A writing life (Virago, 3/23) is one of the finest literary biographies published in Australia, a country that fetishises first books and does scant justice to its finest writers (pace the welcome brace of lives of Frank Moorhouse this year). That literary critic Brigitta Olubas was new to the biographical form only magnifies her achievement in this discerning, consummately researched book. She captures the hurts, the glamour, the pretensions of Hazzard’s life. Better still, she sends us back, armed with new clues, to the novels and short stories. Last, and just finished: The Visionaries by Wolfram Eilenberger, who seems to be offering a kind of ‘salvation of philosophy’ of his own, as in his subtitle. Stirring it was to read of the flight of Arendt, Benjamin, and Weil from the Nazis in 1940, given recent godawful developments in the Middle East.

Tony Birch

I read many novels this year. My favourite was Briohny Doyle’s Why We Are Here (Vintage, 9/23), a story of love, disabling grief, and the raw courage of the novel’s protagonist, ‘BB’. This is a book I will return to again and again. Graham Akhurst’s début novel, Borderland deals with issues confronting young First Nations people. The central characters in the story, Jono and Jenny, embark on a journey, discovering their true selves, their shared heart and Country within a contemporary Australian landscape. For those (like me) who know that Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska is one of the greatest musical albums of all time, Warren Zanes’s Deliver Me from Nowhere: The making of Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska (Crown) affirms our conviction.

Geordie Williamson

J.M. Coetzee’s novella The Pole and Other Stories (Text, 7/23) occupies the same relation to the author’s oeuvre as Beethoven’s late piano works did for his: simpler, yet stranger. Witold and Beatriz’s story is the pure, heady distillate of a remarkable life’s work. Weirder still is English author M. John Harrison’s brilliant ‘anti-memoir’ Wish I was Here (Serpent’s Tail). This is an autobiography without a subject that shades into a writers manifesto whose mission remains obscure. Think of the book as a space shaped so that readers ‘can only navigate with a kind of emotional sonar’. Finally, two titles for a dark year locally – one in which non-Indigenous Australia has, once again, failed to embrace either its past or future: David Marr’s scarifying account of nineteenth-century frontier violence in Killing for Country: A family story (Black Inc., 10/23) and Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy, an epic, addled, visionary examination of the contemporary implications of those foundational crimes.

Yves Rees

As a 2024 Stella Prize judge, my lips are sealed on (most) new releases by Australian women and non-binary writers – but I can say it’s a knockout year in local publishing. Other notable reads include Noah Riseman’s Transgender Australia: A history since 1900 (Melbourne University Publishing, 11/23). In this pioneering history, Riseman shows beyond doubt that trans is nothing new. Contrary to what conservative naysayers may suggest, gender diversity has always been part of the human experience on this continent. Released against the backdrop of neo-Nazi attacks on the trans community, Riseman’s history could not be more timely or necessary. Dan Hogan’s Secret Third Thing (Cordite, 12/23) also deserves mention. In this début collection from the multi-award-winning poet (who was also shortlisted for the 2023 Calibre Essay Prize), Hogan confirms their place as a wildly inventive wordsmith whose work is as playful as it is political. Australian poetry is having a moment, and Dan Hogan is one to watch.

Diane Stubbings

In The Wolves of Eternity (Vintage) – Karl Ove Knausgaard’s companion novel to The Morning Star (2021) – characters spiral like matter around a point of transcendent singularity. Knausgaard dissects the profound tension between the mundane and the extramundane, the wholeness of self and its inevitable splintering. Few contemporary writers are so utterly enthralling. Mike McCormack’s This Plague of Souls (Tramp Press) is one of the most intriguing and distinctive novels I’ve read in some time. A finely balanced account of the memories evoked when its protagonist, Nealon, returns home after a stint in prison, the novel morphs into a mystifying, yet compelling, interrogation of purpose and providence. The Guest Lecture by Martin Riker (Grove Press) charts the intersection of one woman’s life with the broader political and environmental facets of contemporary society. Hypnotic, intelligent, and beautifully conceived. Paul Lynch’s Booker-shortlisted Prophet Song (Oneworld) is a gut-wrenching account of one family caught within a maelstrom of political violence. A dystopian novel that is all too real.

Frank Bongiorno

David Marr’s Killing for Country has an epic quality that reminded me of Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore. In compelling prose, Marr uses the saga of a family – his own – to show how settler Australia was forged through violence and silence. Kate Fullagar’s Bennelong & Phillip, while also dealing with relations between colonial invaders and Indigenous people, works in the opposite direction. By beginning with the deaths and posthumous reputations of the two characters in her dual biography and then working backwards, Fullagar challenges the relentless forward march of time characteristic of imperial and national histories. It is a brave, experimental, ground-breaking history. The second book in Sally Young’s trilogy on the history of Australian media and politics, Media Monsters: The transformation of Australia’s newspaper empires (UNSW Press, 7/23), was a tour through territory often embarrassingly unfamiliar to me. Young is an expert guide.

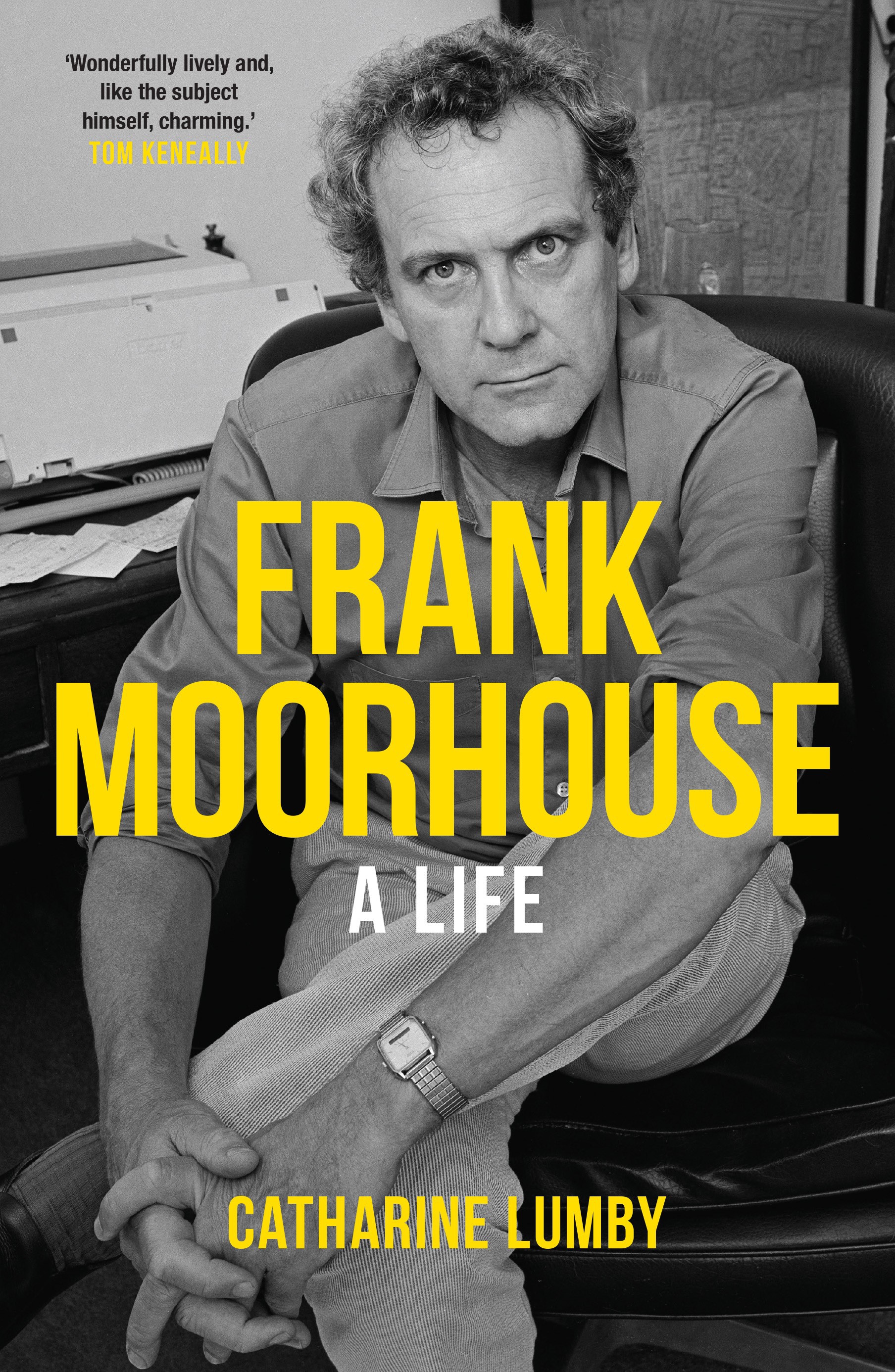

Glyn Davis

The year of a failed referendum sees bittersweet writing from Australia’s First Peoples. It is invidious to pick just one from the many hopeful guides to the Uluru Statement, but Thomas Mayo’s The Voice to Parliament Handbook (Hardie Grant Books), written with Kerry O’Brien, spoke eloquently to the issues. In a different register, David Marr’s Killing for Country is unflinching in describing the frontier wars. Otherwise unremarkable people prove capable of extraordinary cruelty, in a foundation story still little told. Elsewhere, biographies continue to shape memory and understanding, notably Catherine Lumby’s study of Frank Moorhouse: A life (Allen & Unwin, 11/23) and Ryan Cropp’s Donald Horne. Australian poets continue to impress, with Kathryn Lomer’s AfterLife (Puncher & Wattmann) evoking loneliness after love in Tasmanian landscapes exact and imaged. My favourite novels of the year look abroad: to Zadie Smith’s The Fraud (Hamish Hamilton), about a trial which merges class, race, and greed; Ali Smith’s Companion Piece (Penguin), with intriguing fragments evoking pandemic: and Martin Riker’s The Guest Lecture. In a stream of nervous consciousness, an economist lies in bed, near her sleeping family, agonising over career, choices, and the work of John Maynard Keynes.

Gideon Haigh

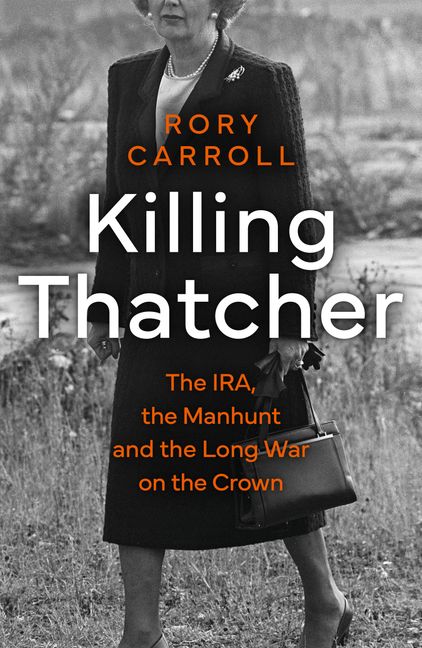

The Troubles exert an unfailing grip on imagination. In similar vein to Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing (2018), Guardian correspondent Rory Carroll’s Killing Thatcher: The IRA, the manhunt and the long war on the Crown (HarperCollins) is a brilliant work of reportage about the 1984 bombing of the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton, starting year by year and condensing steadily to second by second, so that even familiar events grow suspenseful. For readers of John Banville’s The Book of Evidence (1989) comes the story on which it was based. Mark O’Connell’s A Thread of Violence: A story of truth, invention and murder (Granta) concerns the tangled tale of Malcolm Macarthur, scholar, sophisticate, and stone-cold killer.

James Ley

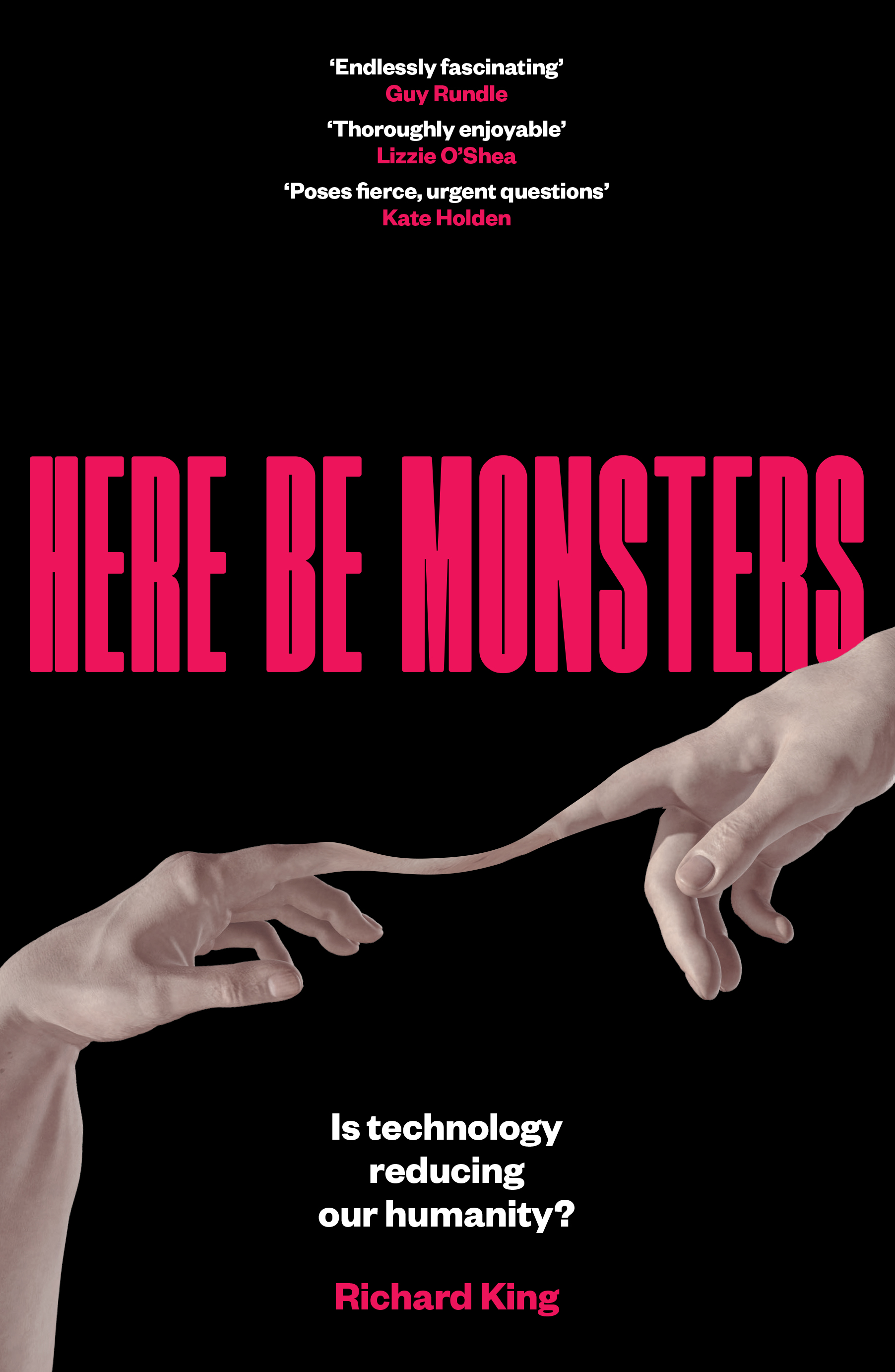

This year, I enjoyed Han Kang’s novel Greek Lessons (Hamish Hamilton), a slim and elegantly composed reflection on the twinned themes of suffering and loss, language and communication. A more fragmented and lyrical work than Han’s best-known book, The Vegetarian (2007), it nevertheless has a quiet intensity that is every bit as impressive. I also found Benjamin Labatut’s The Maniac (Pushkin) particularly engrossing. Presented in the form of a fictionalised oral biography of the scientific polymath John von Neumann, The Maniac is an extended and ultimately disturbing essay on the limitations and dangers of rationalism and the rise of artificial intelligence. On a related note, Richard King’s Here Be Monsters: Is technology reducing our humanity? (Monash University Publishing, 8/23) is well worth checking out as an intelligent and highly readable guide to the brave new world of technology.

John Hawke

The revived attention to women of the surrealist movement has seen the publication this year of major editions of poetry by the Swiss artist, Méret Oppenheim – The Loveliest Vowel Empties: Collected poems (World Poetry Books) – and of the violently transgressive Franco-Egyptian poet, Joyce Mansour: Emerald Wounds: Selected Poems of Joyce Mansour (City Lights). The volume I have returned to most often draws on this tradition. It Must be a Misunderstanding (New Directions), by the contemporary Mexican neo-baroque poet Coral Bracho, is an emotionally devastating reflection on her mother’s dementia. In his poem on the same subject, ‘In Departing Light’, Robert Gray expresses concern that his mother ‘has become a surrealist poet’: Bracho uses this recognition as a vital mode of poetic enquiry. Locally, Alan Wearne’s selection of narrative poems, Near Believing (Puncher & Wattmann, 11/22) was finally launched after long Covid delays. Wearne’s impressionistic survey of social milieux across postwar Australian history is a major contribution to our literature, and deserves a wide general readership.

Beejay Silcox

As chair of this year’s Stella Prize, I’m not able to divulge my favourite Aussie books just yet – you’ll have to wait for the longlist. But what a list it will be! The future of Oz Lit is retina-burning bright. Beyond our shores, two shape-shifting novels captivated me this year: one intertextual; the other, inter-galactic. In Blackouts (Granta), American author Justin Torres conjures a queer-Gothic version of the Hotel California. It’s a tale of cultural resilience and the dark psycho-history of American medicine. ‘From a certain distance, the catastrophic must be indistinguishable from the sublime,’ Torres writes. That’s what he manages in this magnificent meta-fiction – to hold us at the right distance. Cruelly robbed of the Booker Prize (the joy of which is disagreeing with it), Martin MacInnes’s eco-epic In Ascension (Atlantic) is proof – if more was needed – that the Scottish author is one of the most inspired conceptual writers on (and of) the planet.

Michael Hofmann

I had only one substantial difference of opinion with the late and much-missed Dennis O’Driscoll. It concerned the Polish poet Adam Zagajewski. He didn’t care for Adam’s work, and I did. Now he’s dead, and so is Adam, and we shall never know the rights of it. The poems in the ironically entitled True Life (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), published posthumously, have all the hallmarks of late work: weightlessness, speed, blurt, a scribbled calligraphy. They are neither buying nor selling anything. ‘The Old Painter on a Walk’ goes like this: ‘In his pockets treat for local dogs / He sees almost nothing now / He almost doesn’t notice trees suburban villas / He knows every stone here / I painted it all, tried to paint my thoughts / And caught so little / The world still grows it grows relentlessly / And yet there is always less of it.’ Translator Clare Cavanagh is, as ever, a gift to her author. It is sad to think he will never set an adverb again.

Kieran Pender

David Marr’s Killing for Country is an important exercise in truth-telling when, as events this year sadly demonstrated, too many Australians would rather forget the colonial violence at the heart of our nation’s history. Ellen van Neerven’s Personal Score: Sport, culture, identity (UQP) – a unique, poetic memoir and meditation on gender, sexuality, identity, and sport – felt timely as Women’s World Cup fever gripped the nation. My non-Australian book of the year is the engrossing High Caucasus: A mountain quest in Russia’s haunted hinterland (Hachette) by Tom Parfitt. A long-time Russia correspondent for English newspapers, Parfitt embarked on an epic 1,000-kilometre hike from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea in 2008 to deal with trauma, after reporting on the Beslan school siege. Part travelogue, part political history of a fascinating, complex region, High Caucasus takes the reader on a pacy, compelling journey.

Marilyn Lake

Two bold new books – one by an Australian historian examining changes in capitalism in the imperial ‘Anglophone world’, the other by a US philosopher, currently working in Germany – offer fresh thinking about the political and social outcomes of the ‘moral revolution’ effected by neoliberalism. Hannah Forsyth’s Virtue Capitalists offers a transnational account of the rise and decline of the professional class, replaced by an ascendant managerial class, presiding over a regime of ‘moral deskilling’ as it prioritises moneymaking and profit. In Left is not Woke (Polity), Susan Neiman calls for a return to the values of universal humanism, the distinction between justice and power, and the possibility of progress. In a world now ruled by ‘responsibility to shareholders’, Neiman reminds us of the importance of reclaiming the idea of ‘social rights’.

Lynette Russell

While at first this book seems to be a collection of essays written in a memoir format, Gemma Nisbet’s The Things We Live With: Essays on uncertainty (Upswell, 12/23) is an exploration of our often contradictory relationship with objects. Nisbet inherits her father’s and her father’s father’s collections. From macabre objects like her own discoloured baby teeth to the strange plastic array of tourist magnets, Nesbit interrogates the ambivalent feelings generated by the detritus of another’s life. When does a collection become a hoard, or indeed a collector become a hoarder? This is a question that we are allowed to ponder through her careful charting of the unpacking of her father’s possessions. What did the unknown portrait of a nondescript man mean, and why had it been carefully included in each move the family made? More questions than answers, all beautifully and lyrically described. This is a book for anyone who loves things.

Brenda Walker

Killing for Country is David Marr’s meticulous account of the wholesale and slyly – or overtly – sanctioned massacres perpetrated by the Native Police for the benefit of leaseholders on the sheep-runs of colonial Australia. Marr’s work began as a benign enquiry into his maternal antecedents. The discovery that his great-great grandfather was an officer of the Native Police transformed personal history into a precise and sardonic study of pathological violence, rape, child theft, judicial expediency, the denial of Aboriginal testimony (until 1876), contempt for the Aboriginal access provisions of pastoral leases, influence-peddling, and greed. This story would seem like a dark satire were it not for the fact that it is cruel and true. It would be too difficult to read were it not for Marr’s elegant, insistent style. This is a timely year for such a significant book.

Mark McKenna

This year, three works of history stood out. David Marr’s Killing for Country is a gripping and forensic examination of frontier violence that forces the reader to confront the injustice and inhumanity of modern Australia’s foundation. Kate Fullagar’s Bennelong & Phillip reminds us why history is such an exciting and rewarding discipline. Fullagar enters the well-trodden territory of the first years of the British invasion in colonial New South Wales and, by giving equal weight to the lives of two of the period’s most central figures, allows us to see their world anew. Stuart Ward’s Untied Kingdom: A global history of Britain (Cambridge University Press, 8/23), which tracks the unravelling of Britishness in the second half of the twentieth century, is unmatched for its intellectual verve, geographical span, and the quality of its historical analysis. Finally, I enjoyed Catharine Lumby’s Frank Moorhouse, which circles Moorhouse’s life, diving in here and there, and captures her subject’s warmth and mercurial intelligence. Although I was close to the book in the lead-up to publication, Ryan Cropp’s biography of Donald Horne is surely one of the sharpest, lucidest, and most compelling biographies of the past few years.

James Bradley

My most unforgettable reading experience of 2023 was undoubtedly American author Stephen Markley’s The Deluge (Simon & Schuster). A densely imagined, deeply researched, and frequently overwhelming portrait of global unravelling and eventual transformation as a result of climate change, it does a better job of imagining the human, economic, and political chaos that is descending upon us than anything I’ve read. I also loved Charlotte Wood’s quietly astonishing Stone Yard Devotional, a book which draws together the preoccupations of Wood’s earlier novels in powerfully suggestive ways, and cements her place as a major novelist. Gretchen Shirm’s The Crying Room (Transit Lounge) is also a quiet marvel of a book – beautiful, elusive, and deeply felt. And Thom van Dooren’s marvellous A World in a Shell: Snail stories in a time of extinction (MIT Press) offers a compelling and affecting field report from the frontline of the biodiversity crisis.

Des Cowley

Sebastian Barry’s Old God’s Time (Faber) continues his run of outstanding novels, pitching another of his world-weary protagonists – on this occasion Tom Kettle – against an Ireland bogged down in tradition and prejudice. Barry’s language and rhythmic prose are so ear-perfect, it strikes me as unconscionable that he failed to make the cut for this year’s Booker Prize. I approached Richard Flanagan’s Question 7 (Knopf, 11/23) with some trepidation, having been disappointed by his recent work. Fashioned in hybrid form – neither fully fledged memoir nor novel – his meditation on the mutability of family, place, the past, is imbued with wistful nostalgia, one that resonates deeply. It is by far his finest work since the underappreciated Wanting (2008). And any year that offers up 143 new pieces – should we call them stories, fictions, micro-fictions, poems? – by Lydia Davis is a laudable one. By turn witty, abstract, minimal, obtuse, her new book Our Strangers (Canongate) is to be savoured.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.