Diary

Film | Theatre | Art | Opera | Music | Television | Festivals

Welcome to ABR Arts, home to some of Australia's best arts journalism. We review film, theatre, opera, music, television, art exhibitions – and more. To read ABR Arts articles in full, subscribe to ABR or take out an ABR Arts subscription. Both packages give full access to our arts reviews the moment they are published online and to our extensive arts archive.

Meanwhile, the ABR Arts e-newsletter, published every second Tuesday, will keep you up-to-date as to our recent arts reviews.

Recent reviews

January 5: Planning for the Australian Poetry Centre (APC), thanks to the largesse of CAL; we’ll be in ‘Glenfern’, the handsome Boyd/a’Beckett house in St Kilda. Otherwise I’m feeling fit as a whippet, unlike Peter Costello.

January 17: Drove to windy Ballarat for Jan Senbergs’s drawings, David Hansen keeping us wittily diverted – the drawings, after 1992, suddenly very good, as Jan’s crowded Middle Park studio had given him cramped interiors, away from surreal cities. Out in the street, I saw someone who resembled Paul Kane, and uttered a tentative ‘Paul?’ – there they were, Paul and Tina, far from New York – so they persuaded us to drive north, coming to side roads that, like Donne’s pursuit of truth, ‘about must and about must go’. It perched on the bald head of an old volcano, in the full tug of wind: ‘The council engineer said we had to chain it to the hill.’

... (read more)Some weeks ago, I visited my friend Leideke Galema, a Dutch nun who lives in comfortable retirement on the outskirts of Arnhem in the eastern Netherlands. I knew Miss Galema years ago when, living in the belfry of the church of S. Agnese in Agone on the Piazza Navona in Rome, she and her co-religious Miss Koet hired me as a general dogsbody, telephone-answerer, plant-waterer and errand-runner. It was heaven.

... (read more)In the park outside my hotel in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, there is a splendid statue in bronze of President James Garfield, modelled in 1885 by one Charles H. Niehaus and cast in Rome. The pose is oratorical and forms a convenient hub for several witty panhandlers. Somebody has lodged a Panasonic logo high up inside the twentieth president’s lapel. The Cincinnati Club is down the block, a huge post-Albertian palazzo that would have made the Gonzagas blush. For a wedding, floor-to-ceiling arrangements of white and pink roses and several truckloads of lily of the valley effervesce upstairs amid chandeliers, while jungly orchids creep down the front hall banisters – all clearly visible from the other side of the street. Obviously, they have invited only the immediate country. Around the corner is a hat shop from another era, with the elevated thrones of a separate shoe-shine department running down one side, and a fully operational hat-steamer snorting among stacks of boxes behind the wide counter opposite. I find myself being fitted for a beautiful pork-pie hat by Biltmore of Canada.

... (read more)When I was at school, I was infected by the idea that writing was a genteel art. Set to read The Prince for its political insights, I was captivated by a single image: Machiavelli coming in from the fields of an evening, washing the sweat from his body, slipping on his silken robe, seating himself at his desk – and writing. That picture leapt straight from the page into what passes for my soul. I knew that was where I wanted to fetch up: at that desk, in my silken robe, writing. The glorious lucidity of Machiavelli’s prose also confirmed my suspicion that books were magical extrusions into the muddy mundane from a calm, blessed place where people could think important thoughts even talk about them, without being told to please, please shut up and feed the cat.

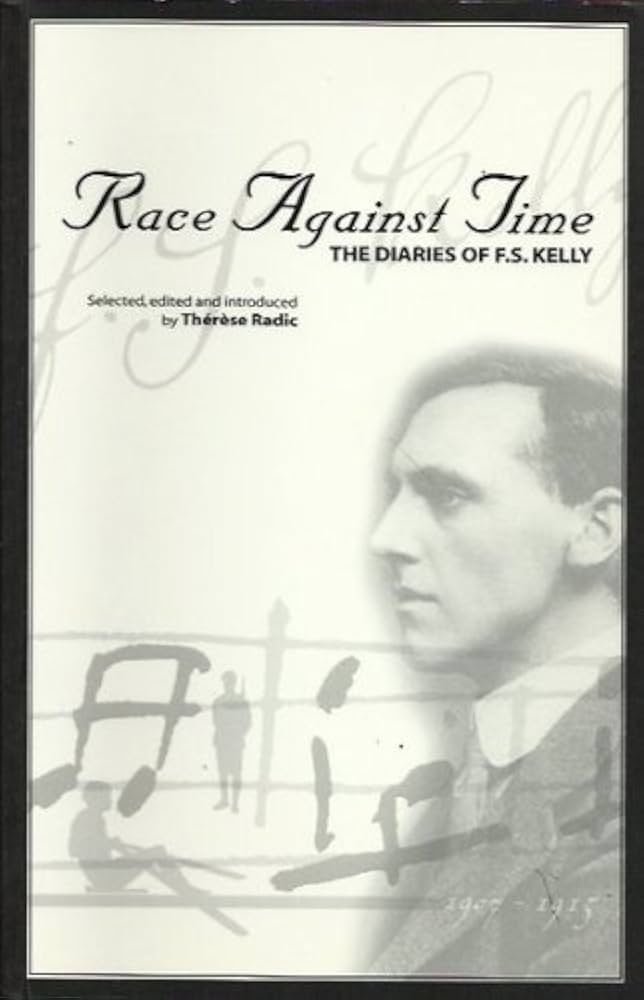

... (read more)Race Against Time: The diaries of F.S.Kelly edited by Thérèse Radic

During the summer, Fire Island Pines, a scrubby Atlantic-facing dunescape off the southern shore of Long Island, is entirely colonised by gay men from Manhattan. Little dogs, swelling pectorals, postcards of Prince William and other clichés abound. The only way to get there is by ferry. There are no roads, just paths, jetties and boardwalks. This alone makes it worth the trip. Yet Fire Island has a distinctly ‘science fiction’ aspect, as if a cruisy gay nightclub in outer space for curious aliens and time-travellers. Here, glamorous youth and leathery, wobbling-tummied capital are exquisitely interdependent. From about four o’clock in the afternoon until six or seven, at the quayside tea dance, hundreds of shirtless men writhe to ‘Let the Sunshine in’ and other camp classics. All shapes and sizes. You can’t help thinking of those nature documentaries where colourful water birds peck grubs and insects from behind the ear of some lumbering wildebeest. I am not sure where I fit into this eco-system. It does not seem particularly fragile.

... (read more)September 18

Arrival in Savannah, Georgia, a town that seems to have at least seven syllables to its name. The heat is grey and sullen: the famous Spanish moss on the trees crackles at a touch. Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil is everywhere; the place gives a general impression of being quite pleased with itself, though both wealth and poverty are sharply obvious. An odd place, perhaps, to look for the pianist and social reformer Hephzibah Menuhin, whose biography I’m in the northern hemisphere to research, especially since she never came here. But Savannah is only a step away from Beaufort, South Carolina, and this is where Hephzibah’s daughter Clara Menuhin Hauser lives. Clara is very important indeed

... (read more)It’s the silence. Even by the river, my ears are straining. It’s the silence. At this moment it’s a warmish humid silence with the grass outside lushly mesmerising the eye.

... (read more)‘It’s the essence of Bollockshire / you’re after: its secrets, blessings and bounties.’ So Christopher Reid reads from his hilarious poem at the King’s Lynn Poetry Festival.

park and pay ...

assuming this isn’t the week

of the Billycock Fair, or Boiled Egg Day,

when they elect the Town Fool.

From here, it’s a short step

to the Bailiwick Hall Museum and Arts Centre.

As you enter, ignore the display

of tankards and manacles, the pickled head

of England’s Wisest Woman;

ask, instead, for the Bloke Stone.

Surprisingly small, round and featureless,

pumice-gray,

there it sits, dimly lit,

behind toughened glass, in a room of its own.

... (read more)