Archive

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE: A LITERARY LIFE by William Christie

This year I have read too many American political quickies, and large numbers of somewhat more satisfying detective stories. Amid the revelations about Hillary Clinton’s childhood, and the equally fictitious accounts of intrigue in Istanbul and Venice, a couple of books stand out. Andrew Wilson’s The Lying Tongue (Text) and Stephen Eldred-Grigg’s Shanghai Boy (Vintage) are ‘gay books’ that speak to themes other than sexuality, and deserve to be better known. Although ultimately too improbable, Andrew McGahan’s Underground (Allen & Unwin) evokes rather well a left-wing dystopia, centred on a Howard-like government. As for nonfiction, Tony Judt’s Postwar: Europe since 1945 (Heinemann), while telling us more about Poland and less about Spain than we need know, is a fascinating reminder of the Cold War era, evoked for the other side of the Atlantic in Thomas Mallon’s novel Fellow Travellers (Pantheon).

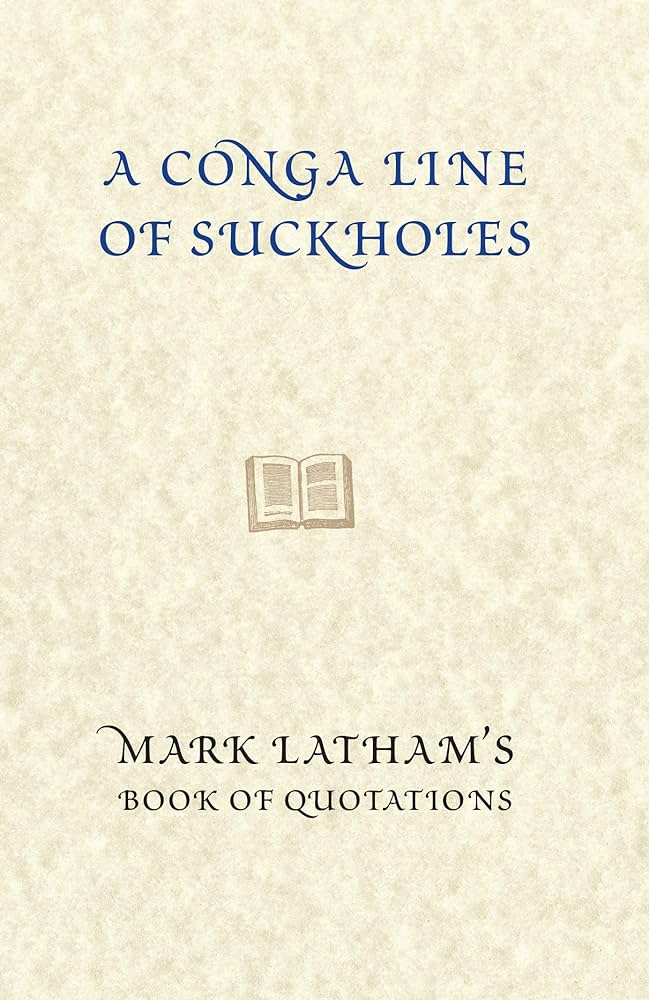

... (read more)A Conga Line of Suckholes: Mark Latham’s book of quotations by Mark Latham

Dennis Altman

In any given year we will read but a tiny handful of potential ‘best books’, so this is no more than a personal selection. Here are two novels that stand out: Stephen Eldred-Grigg’s Shanghai Boy (Vintage) and Hari Kunzru’s Tranmission (Penguin). Both speak of the confusion of identity and emotions caused by rapid displacement across the world. The first is the account of a middle-aged New Zealand teacher who falls disastrously in love while teaching in Shanghai. Transmission takes a naïve young Indian computer programmer to the United States, with remarkable consequences. From a number of political books, let me select two, both from my own publisher, Scribe, which offers, I regret, no kickbacks. One is George Megalogenis’s The Longest Decade; the other, James Carroll’s House of War. Together they provide a depressing but challenging backdrop to understanding the current impasse of the Bush–Howard administrations in Iraq.

... (read more)Tamas Pataki opens his review of Antony Loewenstein’s My Israel Question (October 2006) with a lengthy denunciation of the recent war in Lebanon. He decries Israel’s counterattack against Hezbollah as an ‘atrocity’, citing the ‘awful statistics’ of Lebanon’s larger casualty toll as evidence of the Jewish state’s nefariousness. But this is a curious calculus that ignores questions of who breached the peace by attacking whom, and the ethics of using civilians to shield military operations. The fatuousness of Pataki’s moral yardstick becomes apparent when it is applied to World War II. Germany suffered far greater casualties than the Western Allies. Surely this did not confer upon Nazism the status of righteous victim in that conflict. Pataki uncritically parrots Loewenstein’s contention that Israel’s ‘illegal occupation’ is the ‘cause of legitimate Palestinian resistance’. If by ‘occupation’ he means the territories captured by Israel in 1967, the timeline of conflict tells a different story. The Palestinian Liberation Organisation was founded in 1964 with the goal of Israel’s destruction. Arab violence against Jewish communities in the Holy Land even preceded the establishment of the Jewish state in 1948. So it seems that the ‘cause’ of terrorism is, after all, not Israel’s presence in the West Bank but, rather, Israel’s presence in any form.

... (read more)Kathy Kozlowski

The Library Lion (Walker), by Michelle Knudsen and Kevin Hawkes, is an almost perfect traditional picture book about a gentle creature who becomes enamoured of his local library. It tells a riveting story of misunderstandings made right, and has a really satisfying ending. Guus Kuijer’s The Book of Everything (Allen & Unwin) is an elegant little book, told from the perspective of a sensitive child, whose family is saved from the power of angry religious fervour by neighbourly kindness and common sense.

... (read more)