Archive

Jonestown: The power and the myth of Alan Jones by Chris Masters

by Graeme Turner •

Blessings and praise

to the dark entanglement of caught branches

I continue to see,

after years of crossing the causeway,

as a black swan

holding her place in the current, her head

held resolute and serene,

her cygnets the shadows that advance and recede

in the eddies she makes going nowhere.

... (read more)The body’s peasant workers – hands –

daily toil in the fields of light.

They never question our wishes.

They can fail, but not misunderstand.

They are our strangeness that we are blind to.

At night they lie like maimed spiders

or star fish swept to shore. They know

about love as much as mouths and eyes.

Throughout the day, they give the mouth ... (read more)

daily toil in the fields of light.

They never question our wishes.

They can fail, but not misunderstand.

They are our strangeness that we are blind to.

At night they lie like maimed spiders

or star fish swept to shore. They know

about love as much as mouths and eyes.

Throughout the day, they give the mouth ... (read more)

The Gospel According To Luke by Emily Maguire & Rosie Little’s Cautionary Tales For Girls by Danielle Wood

by Louise Swinn •

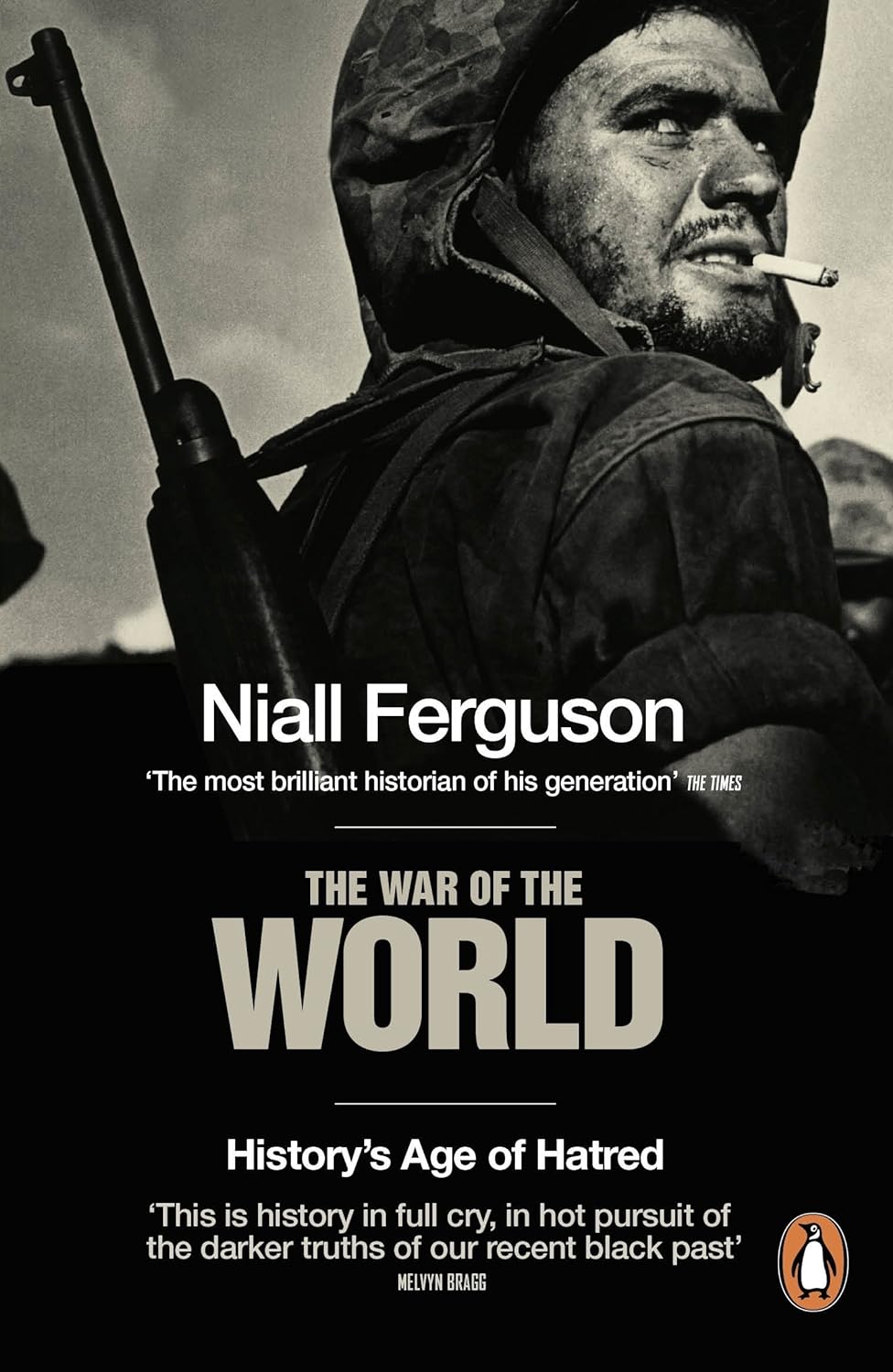

The War of the World: History’s age of hatred by Niall Ferguson

by Geoffrey Blainey •

.jpg)