Art

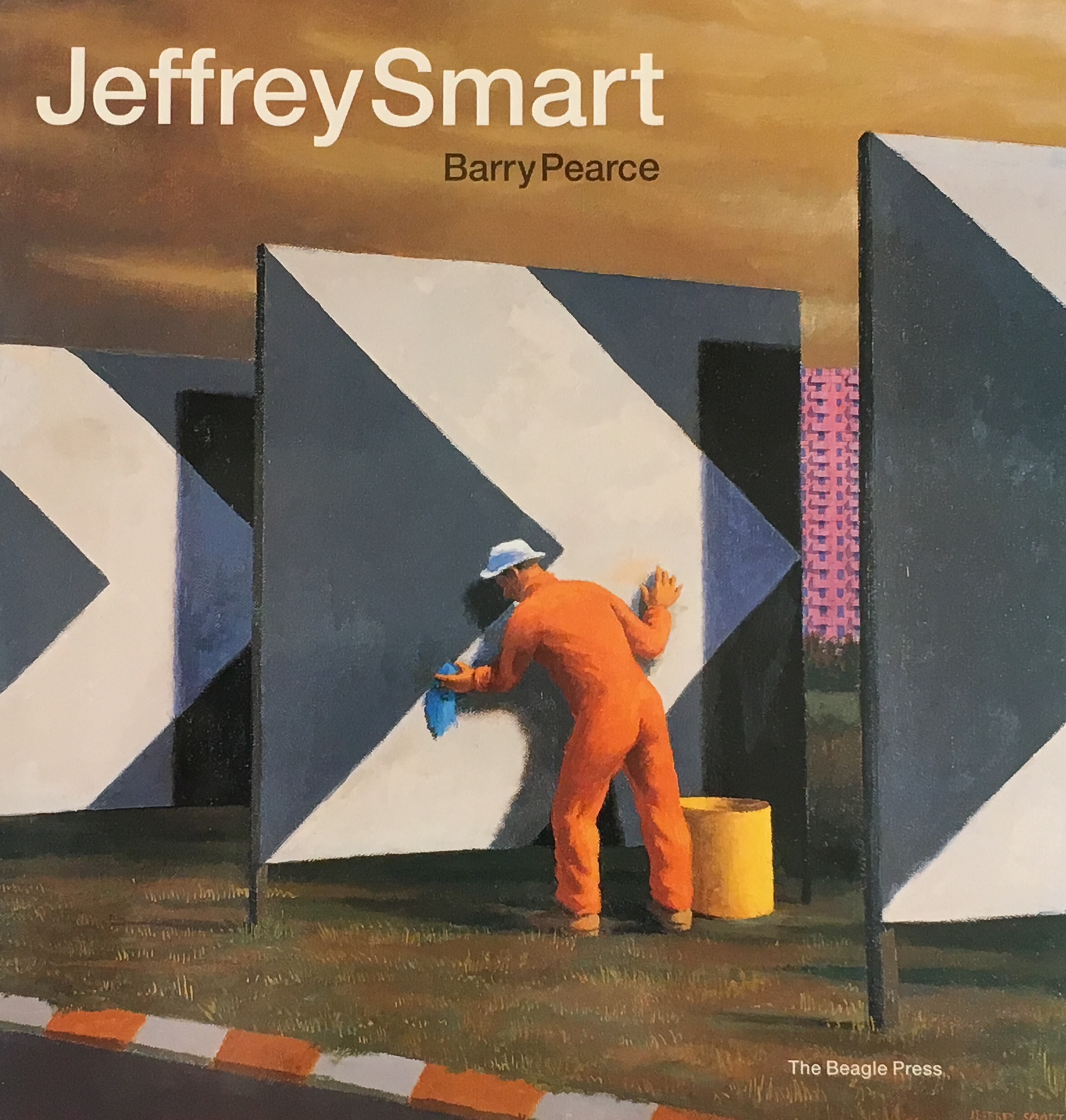

This timely monograph presents the life and work of an artist whose paintings have altered the way we see the modern world, particularly the industrial landscapes fringing our cities. Jeffrey Smart’s intensely realised paintings have the effect of making the ‘familiar strange’. They force us to reconsider both our relation to and perception of man-made environments, dominated as they are by factories, apartment blocks, freeways and street signs. Smart’s paintings display a mastery of classical composition, light and perspective as well as revealing the artist’s ongoing concern with the interplay between realism and abstraction. The 252 plates included in this volume allow the reader to appreciate the development of Smart’s unique oeuvre over a period spanning more than sixty years. Accompanying these illustrations is a text by Australian modernist scholar and curator Barry Pearce. This provides a valuable addition to the existing literature on the artist.

... (read more)The Felton Illuminated Manuscripts in the National Gallery of Victoria by Margaret M. Manion

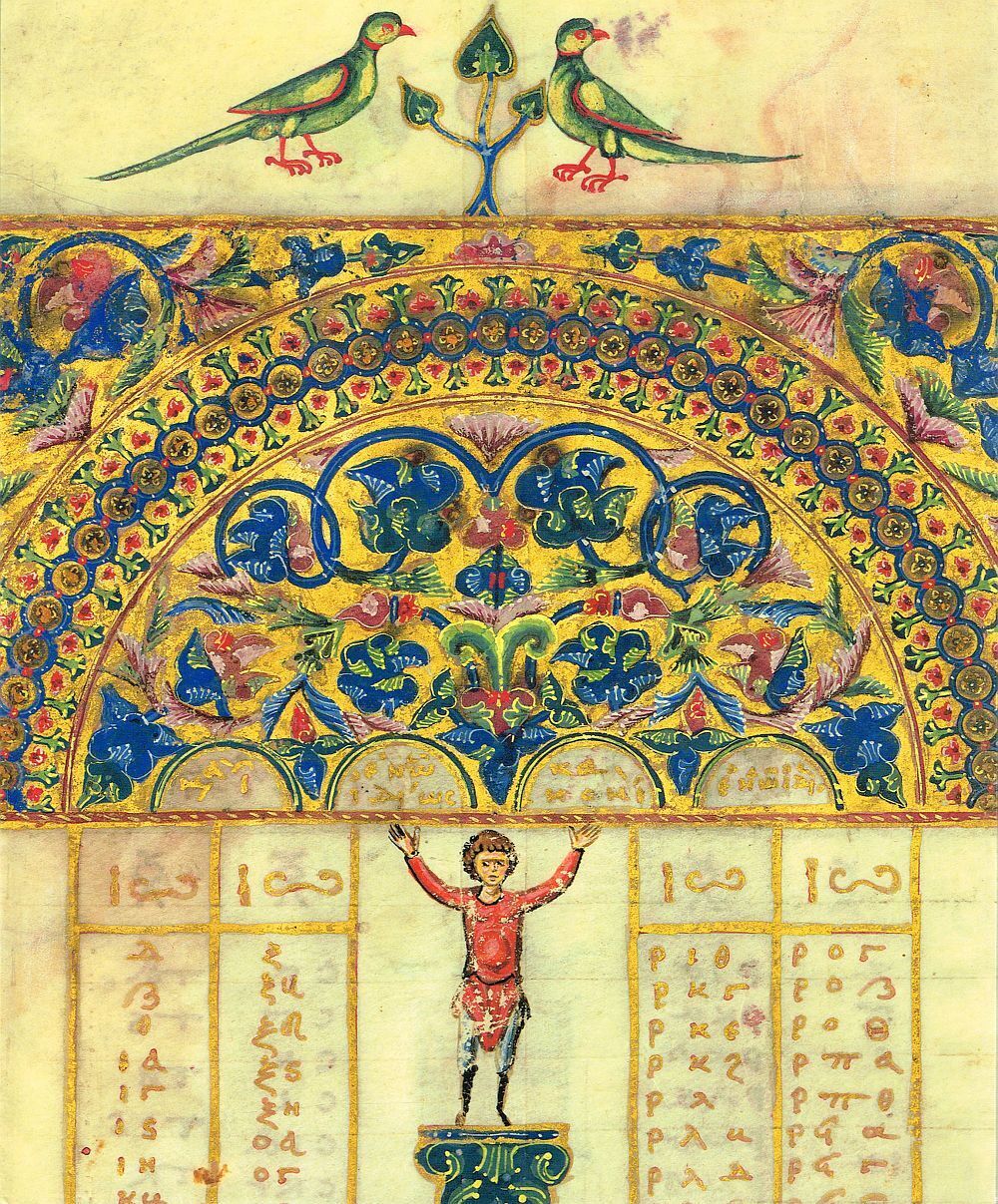

To commemorate the centenary of Alfred Felton’s death in 1904, the National Gallery of Victoria and Macmillan Art Publishing have published the five illuminated medieval manuscripts and the single leaf ac-quired for the Gallery through the Felton Bequest. This stunning volume is profusely illustrated with colour plates taken by the photographic team of the NGV of all the decorative features in the manuscripts; in addition, there are numerous coloured figures of comparative works in other collections. Decorative elements from each Felton manuscript ornament the opening pages of each section, and embellish the title and end pages of the book. In design and illustration, this volume is itself a work of art, with hundreds of coloured images to delight the eye.

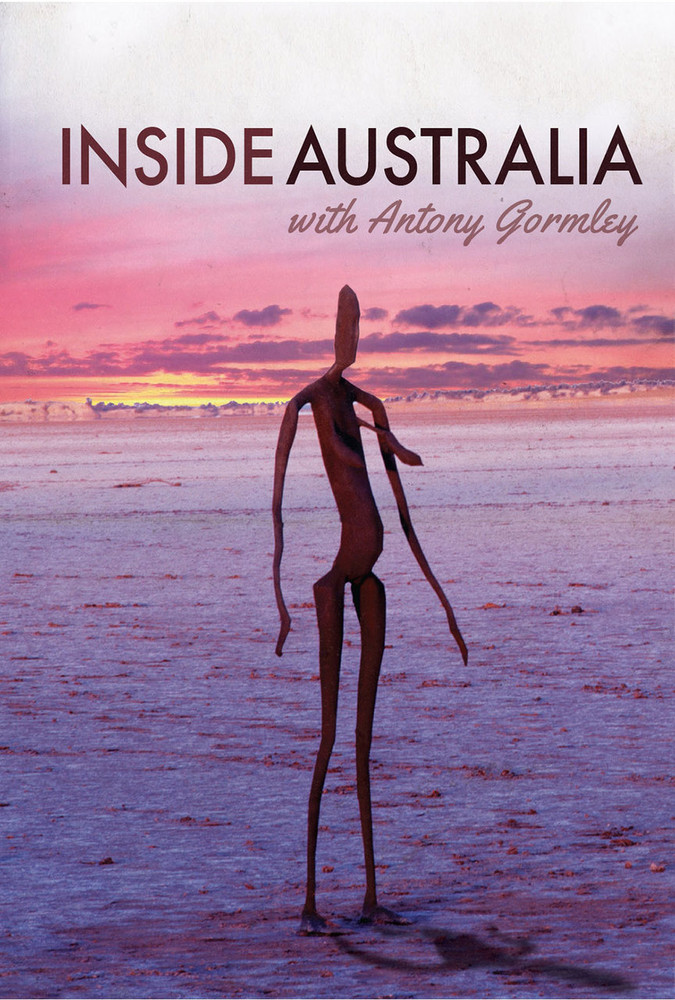

... (read more)Imagine turning up in Menzies, 132 kilometres north of Kalgoorlie and 729 east of Perth in Western Australia, and then inviting the town’s inhabitants to take their clothes off. This is exactly what the British artist Antony Gormley did in June 2002. Improbably perhaps, after some coaxing, 131 people in Menzies, and later in Perth, agreed. Inside Australia documents Gormley’s remarkable artistic project to make and install more than fifty ‘insiders’ over ten square kilometres on Lake Ballard, a salt lake near Menzies. The first step in this process was to take full-body scans of anyone who was willing, to capture each individual’s unique three-dimensional geometry. All the scans were then ‘gormleyised’, that is, reduced by two-thirds. Next, polystyrene models were made from the digital files. Finally, metal figures were cast from the models in the VEEM foundry in Perth.

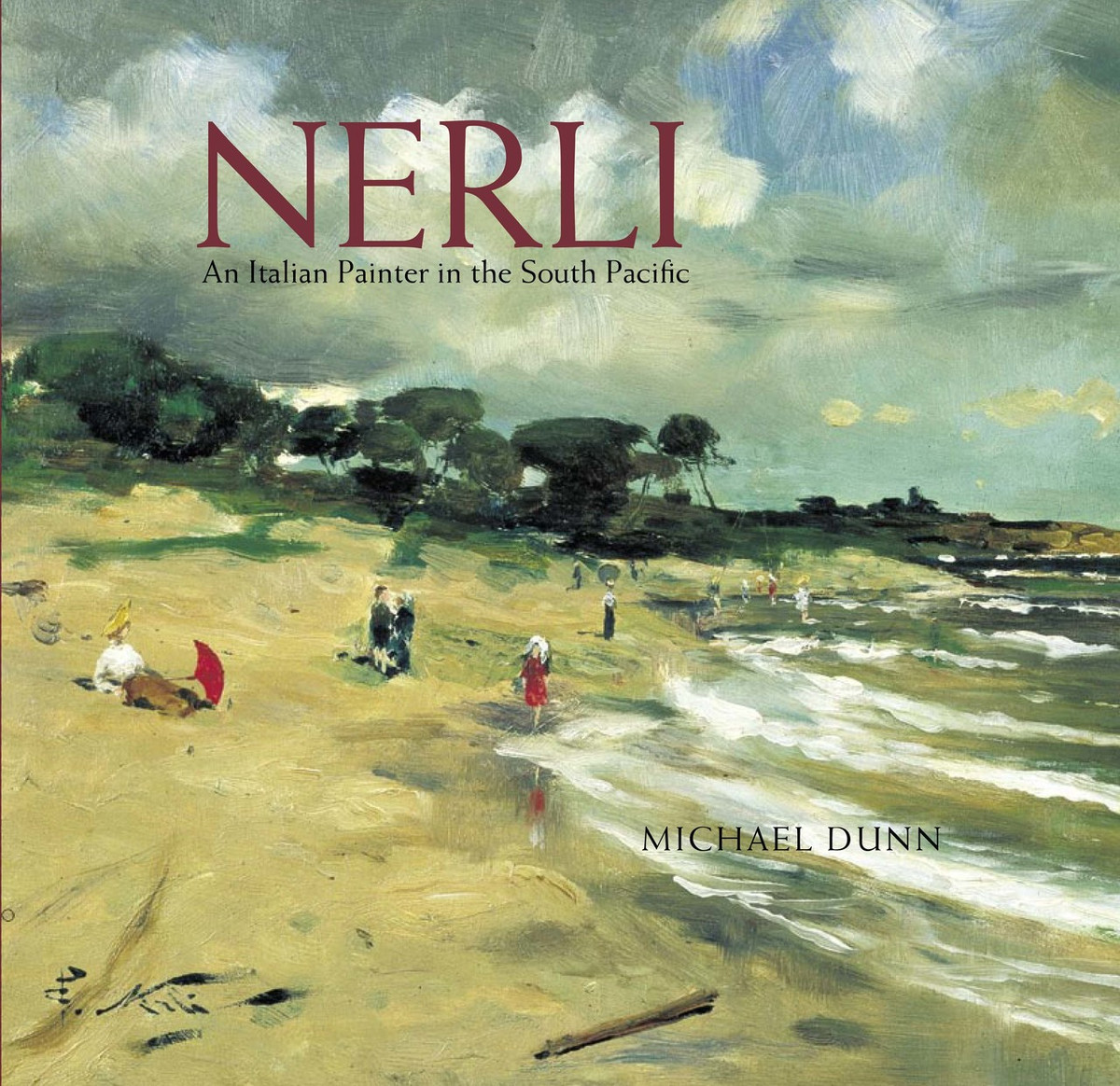

... (read more)Nerli: An Italian painter in the South Pacific by Michael Dunn

Girolamo Nerli, Michael Dunn writes in Nerli: An Italian Painter in the South Pacific, was ‘an uneven painter who ranged from the good to the downright bad’. It says much about the difficult development of the visual arts in Australia and New Zealand that someone with such apparently modest abilities should be worthy of such a lavishly illustrated and comprehensive study – especially in these days of constraint in art-historical publishing. Nerli has generally been depicted as a flamboyant Continental whose European heritage and thick Italian accent imbued him with an authority that made local artists and philistines alike listen receptively to his views. As a foreigner, he was permitted to be ‘irreverent, avant-garde and daring’, in ways denied local artists. Nerli’s place in Australian art history is assured by his association with the Heidelberg School artists, while his brief but influential role as Frances Hodgkin’s teacher secures his place in New Zealand’s art history. In this, the first published extended study of Nerli’s time in Australia and New Zealand (including a foray to Samoa), Dunn seeks a ‘fresh appraisal of the man and his achievements’.

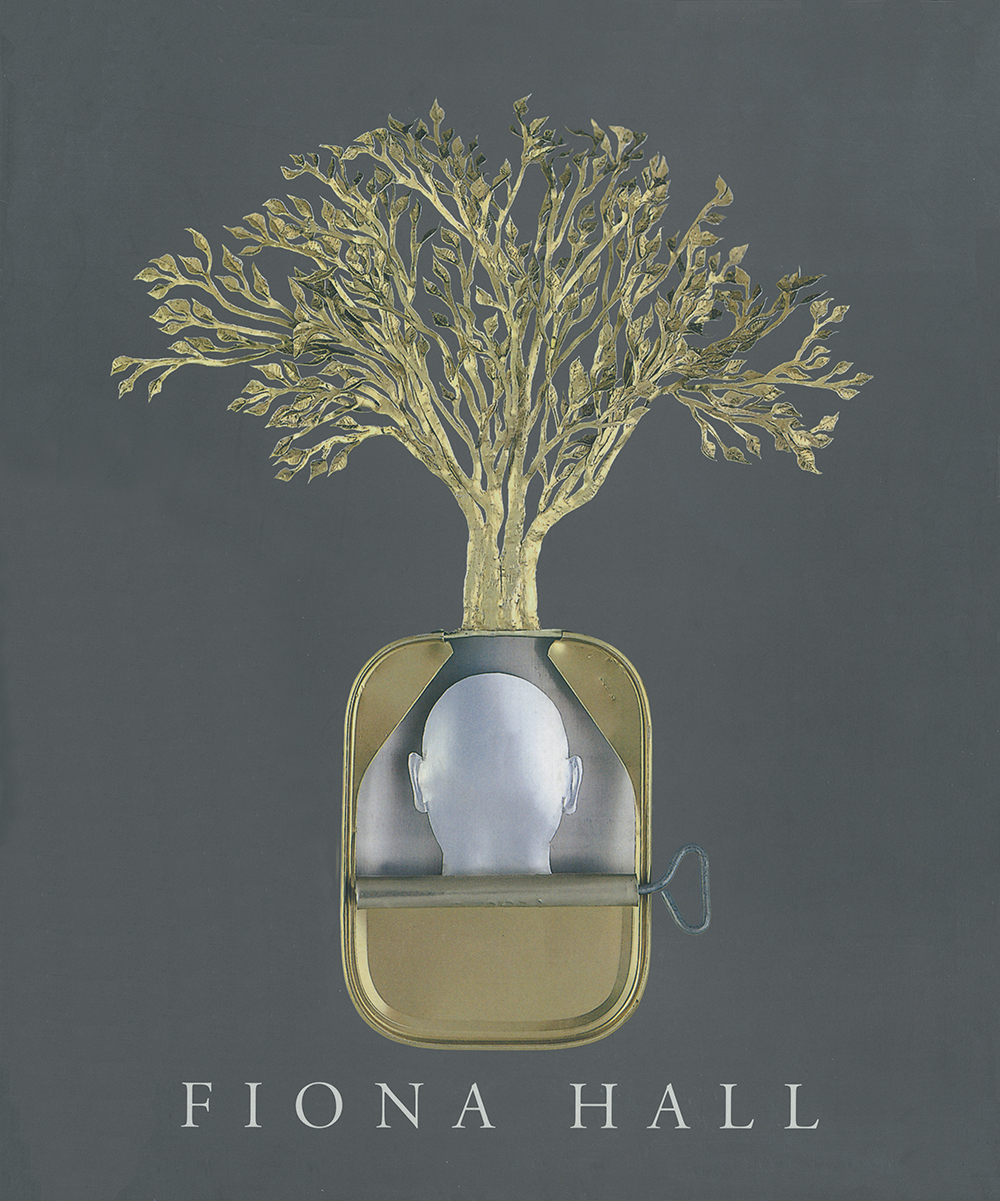

... (read more)For her participation in the 2002 Adelaide Biennial, Fiona Hall encapsulated her recent practice and its emphases on the fragilities of ecosystems, and on the instability of the social and political structures on which our cultures are based. She stated that ‘now we know that the seemingly infinite, disparate variety of living matter on earth, of which we are but a part, is life’s giant, polymorphic skin, encasing us all, inside which we dwell in kindred, genetic proximity’. And so it is that the seemingly infinite possibilities and disparate conceptual and material elements of Hall’s extra-ordinary practice are integrated between the covers of Julie Ewington’s outstanding monograph, Fiona Hall, which was published to coincide with the Queensland Art Gallery’s focused survey of the artist’s work since 1990.

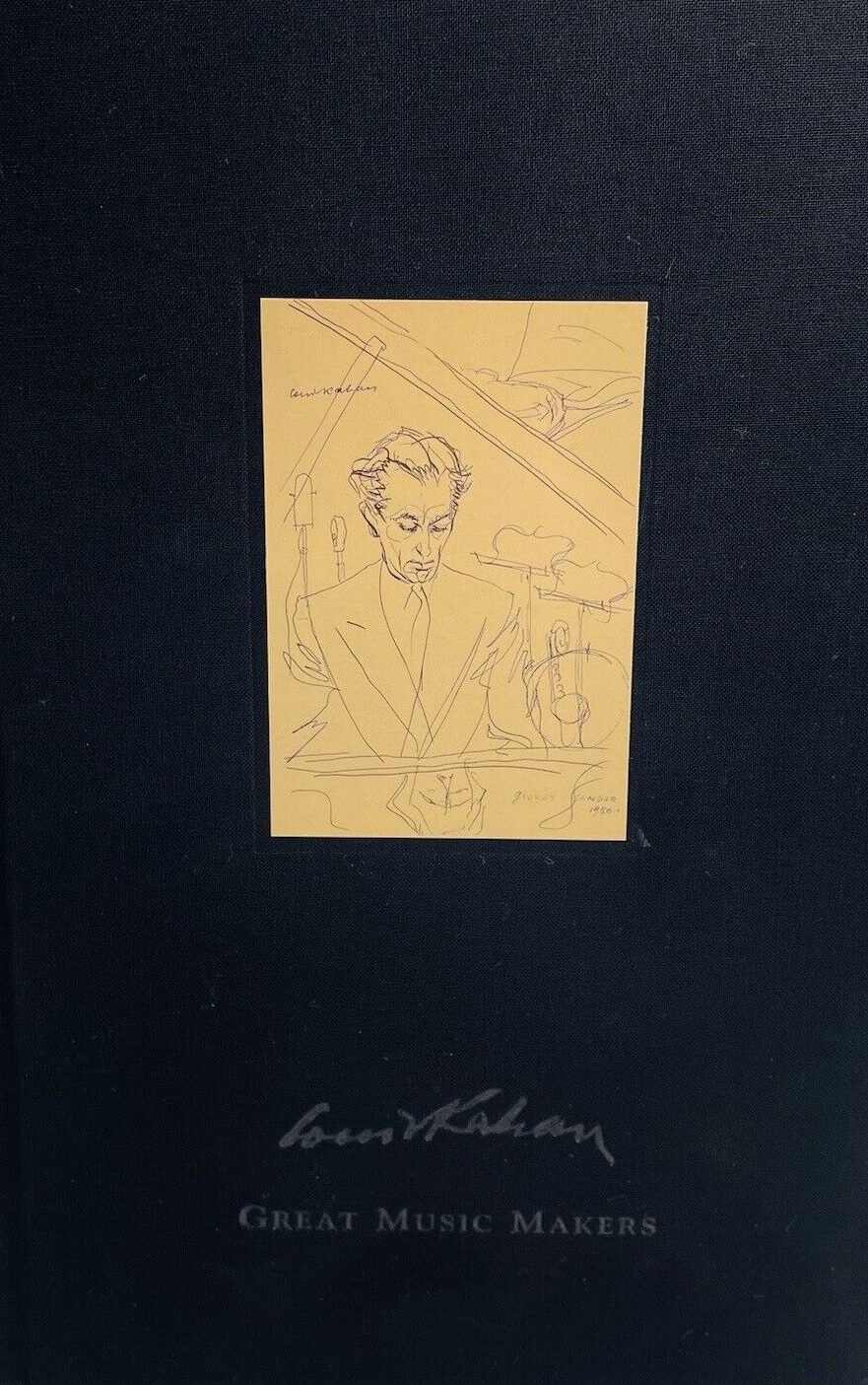

... (read more)ABR readers may be more familiar with Louis Kahan’s illustrations for Clem Christesen’s Meanjin or with his portrait of Patrick White (which won the Archibald Prize in 1965) than with his sketches of musicians, but this stylish book from Macmillan Art Publishing reveals not just the fluidity of Kahan’s style but also his passion for music and music-makers. And what a range of artists he could draw on (mostly at rehearsals) during the second half of his life. Present-day concert-goers, inured to leaner rostrums resulting from high fees and a faded currency, will marvel at the list of luminaries who performed here during the three decades after the war. There is Claudio Arrau (1947), grave and poetic; Otto Klemperer (1950), Olympian, bespectacled; a young Lorin Maazel (1961), gaunt and driven like a Schiele self-portrait; Luciano Pavarotti (1965) before the years of glory and girth; and Marian Anderson (1971), mighty in her sensible hat.

... (read more)Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius by Nikolaus Pevsner

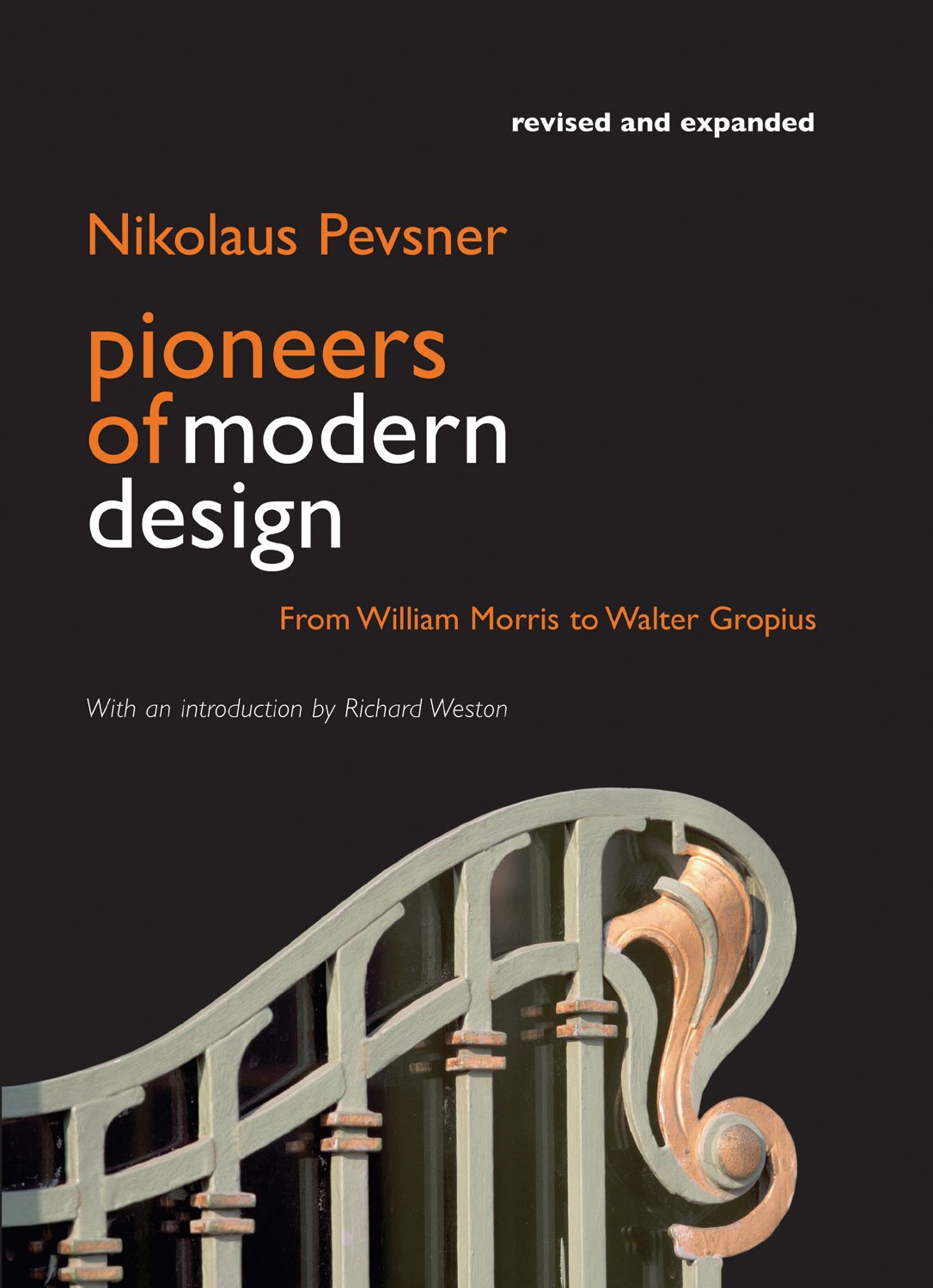

‘All machinery may be beautiful, when it is undecorated even. Do not seek to decorate it. We cannot but think all good machinery is graceful, also, the line of the strength and the line of the beauty being one.’

Although ridiculed in his own day as a fashion victim in dress and manners, Oscar Wilde, the exemplar of the excesses of the Aesthetic Movement, is not normally quoted in design histories. Being Wilde, what he wrote above is probably not in praise of the machine, but its inclusion in Nikolaus Pevsner’s Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius (first published in 1936) shows the breadth of reference in this excellent and now classic introduction to modern design and twentieth-century modernism.

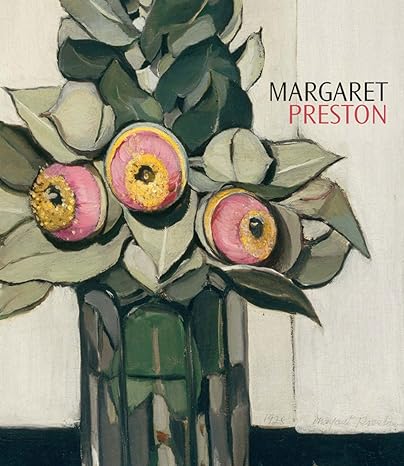

... (read more)Margaret Preston by Deborah Edwards (with Rose Peel et al.) & The Prints of Margaret Preston by Roger Butler

There is something immensely satisfying about a work so ambitious and comprehensive as Deborah Edwards’s Margaret Preston, published by the Art Gallery of New South Wales to accompany its current retrospective on this pre-eminent Australian modernist. From the outset, we are introduced to Preston’s perennial capacity to stimulate not only debate but also downright factionalism. The introductory chapter takes the form of multiple quotes, leaving no doubt that Preston continues to ignite debate over issues surrounding an authentic Australian vision.

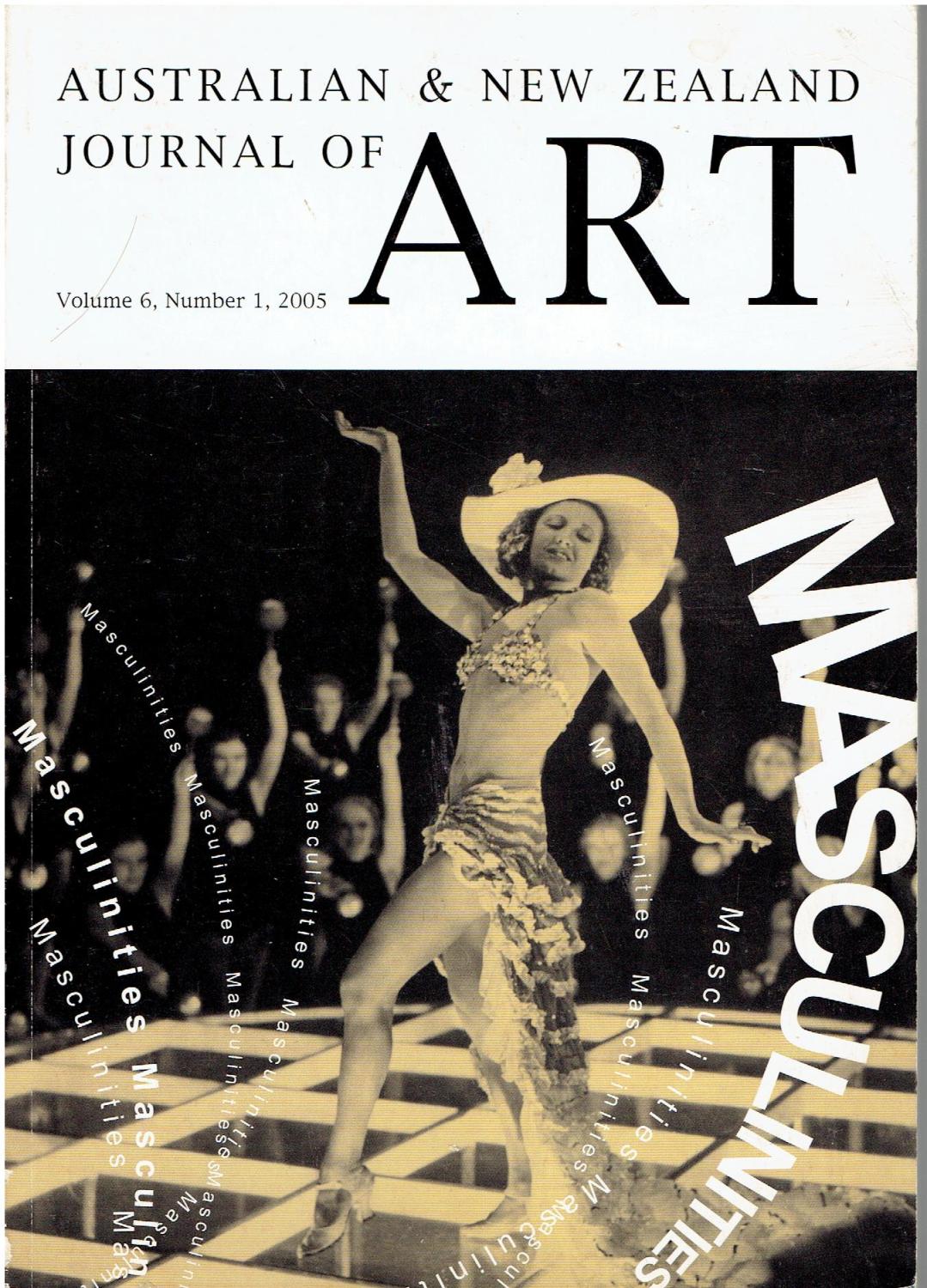

... (read more)Australian & New Zealand Journal of Art: Masculinities, vol. 6, no. 1, 2005 edited by Karen Burns et al.

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art has dedicated its latest issue to the theme of ‘Masculinities’. This is a timely contribution to debates about the construction of male identity in visual and popular culture in the wake of Brokeback Mountain. The controversy this film has generated has focused on the love affair between two cowboys and the threat seemingly posed to an archetypal bastion of manhood, but if you remove the queer element, you have a work that isn’t so different from conventional films such as The Man from Snowy River. A similar quandary is posed by Ross Moore’s standout essay on James Gleeson and the ‘de-gayification’ of his paintings by art writers. Gleeson may have avoided decades of controversy, but delete the queer reading from his imagery and he becomes unproblematically Australia’s greatest surrealist painter.

... (read more)