Archive

The Ghost Names Sing by Dennis Haskell & Album of Domestic Exiles by Andrew Sant

by Brian Henry •

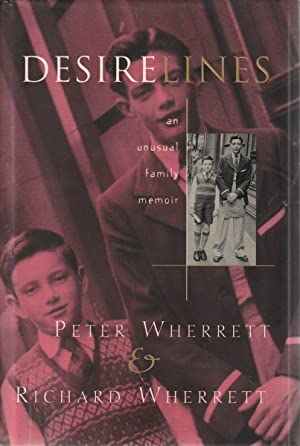

Desirelines: An unusual family memoir by Peter Wherrett and Richard Wherrett

by Kerryn Goldsworthy •

Personal Best edited by Tessa Duder and Peter McFarlane

by Garry Disher •

From Denis Altman

Dear Editor,

I suspect I’m the ‘(male) baby boomer academic who should have known better’ referred to by Delia Falconer in her piece in the Gangland symposium (ABR, November 1997).

... (read more)John Howard: Prime Minister by David Barnett and Pru Goward

by Joe Rich •

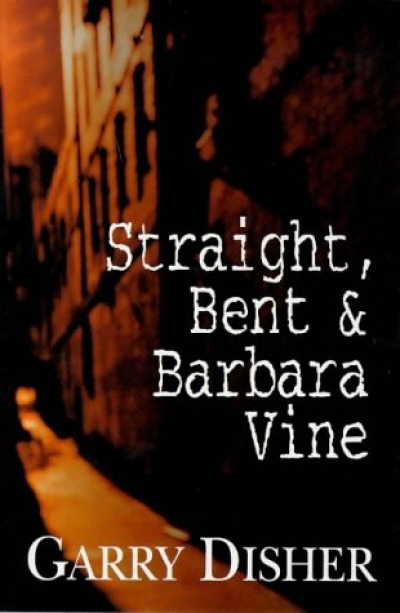

Straight, Bent and Barbara Vine by Garry Disher & Raisins and Almonds by Kerry Greenwood

by Stuart Coupe •

Rise & Shine by David Legge & I Know That by Candida Baker, illustrated by Alison Kubbos

by Nicola Robinson •

Ubu Films: Sydney underground movies 1965-1970 by Peter Mudie

by Juno Gemes •