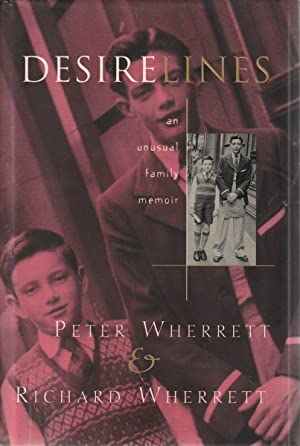

Desirelines: An unusual family memoir

Hodder Headline, $29.95 hb, 304 pp

Cross Lines

Autobiographical tales, at least in Australian culture, tend to come in three kinds: the kind that was written as a self-consciously literary product; the kind that has a unique or sensational angle, or focus, or moment; and the kind that was written by the famous to tell the story of their fame, usually with content well to the fore over style.

But the Wherrett brothers’ Desirelines is a different kind of book again. It is autobiographical but it was written by two people. The sensational angle is something they share. They are both famous, but it is not, or only incidentally is, a book about their fame. Both of them 'can write’, but it was not written as a high-literary book. Desirelines belongs to what has almost become a sub-genre of autobiography, at least in Australia – the harrowing-story-of-the-father book – and recalls books otherwise as widely different from each other as Merv Lilley’s Gatton Man, Germaine Greer’s Daddy, We Hardly Knew You, and even to some extent Sally Morgan’s My Place, as a chronicle of family secrecies and horrors engendered by paternal violence, failure, or silence.

For the figure at the heart of Desirelines is neither of the Wherrett brothers nor even, quite, their long-suffering and much-loved mother. Arthur Eric Wherrett, father of Peter and Richard, schoolboy athletics champion, disappointed suburban pharmacist, epileptic, alcoholic, wife-beating cross-dresser, is the focus of this book, and many of those episodes and reflections which do not involve him directly are presented, or must be read, as having their genesis in his tormented and tormenting self.

This is what the term 'post-feminist really means: it describes an era in which a good explanatory framework has been provided for hitherto inexplicable or, sometimes literally, unspeakable behaviour; an era in which it is possible to acknowledge and speak about constructions of gender and the horrors those constructions could bring on real, ordinary people, setting rigid standards and agendas for sexual and social behaviour at a time when gender difference was regarded as a matter of nature and essence, and ignorance was bliss.

Questions of gender and sexuality have determined the patterns of both Wherrett brothers' private lives, and each examines these in the course of their more or less alternating contributions to the book and as a kind of counterpoint to the stories about the development of their work in public life. Richard, musing on his appointment in 1979 as Director of the Sydney Theatre Company, remarks, ‘I’d entered the 1960s buoyed by the clarification of my sexual identity. I’d entered the 1970s buoyed by the clarification of my national identity. I was now entering the 1980s buoyed by my professional identity.’

It's Richard, also, who, in discussing his production of The Elocution of Benjamin Franklin, provides the clearest brief summary of his father’s and his brother’s practice as cross-dressers: I began to understand that cross-dressing was not essentially a sexual activity, and was most frequently a heterosexual practice of a very complex and sophisticated nature. That this is so is borne out by Peter’s account of the genesis of his own cross-dressing, which he remembers as intricately bound up with childhood fear and rejection of his father:

I am in bed and I am wakened by a noise which turns out to be my father screaming abuse at my mother. The sound is harsh, angry and frightening and I am very much afraid … I get out of bed and pad along the hallway to my parents’ bedroom and open one of my mother's drawers and take out a soft, silky item of her underwear. I carry it back to my bed and I cuddle it … With my security blanket I can survive. The security blanket is my mother and I hold onto her tightly.

I wanted to grow up to be like my mother. I loathed my father. I was in mortal fear of him, and of what he represented, seeing him as the archetypal male … I still have very few male friends and I am still fearful of the male pack mentality.

Disappointingly, this memory doesn’t lead to any speculation about Eric Wherrett's own childhood or where his cross-dressing might have come from, although one of the book's most intriguing images is of Peter, by then well into adolescence discovering his father's frocks and wigs. ‘In this, at least, I was my father’s son. It disturbed me because I didn't want to be like him. And then it occurred to me that he didn’t want to be like him either.’

The Wherrett brothers have between them contributed a great deal over a long time to a broad spectrum of Australian culture: theatre, television, movies, and the sprawling subcultures of car worship. Desirelines is worth reading for its account of that; and for its intriguing account of the psychosexual of a violent father’s sons; and for its vivid picture of a 1950s Australian suburban childhood. But what should really stand out is the skill of Peter Wherrett, who after all spent many hours carefully learning his craft as a journalist, whose writing is in consequence forceful and direct, and whose fishing-with-Father tale at the beginning of the book is one of the best parent stories I’ve read for a long time.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.