Australian History

Painting Ghosts: Australian Women Artists in Wartime by Catherine Speck

Those attending art history conferences over the last few years have been beguiled by the papers given to Catherin Speck, based on her research into aspects of Australian women artists and war. Each paper has detailed newly uncovered artists, works and information, and whetted the appetite for Painting Ghosts: Australian Women Artists in Wartime: not a reproduction of Speck’s previous work but fresh information, artists and images (such as Adelaide painter Marjorie Gwynne) placed into better-known depictions of war by artists such as Hilda Rix Nicholas and Nora Heysen.

... (read more)Liz Conor’s accomplished history of the ‘modern appearing woman’ in 1920s Australia has much to recommend it. The archival work that it represents is fascinating and suggestive of a trove of female energy, sadness and invention. Hilarious and ambivalent stories emerge of Sydney ‘gals’ and Business Girls, of a New York flapper with traffic lights painted on her silk stockings, and of Amelia, an indigenous maidservant, who invented grunge without her mistress recognising style when it stepped up to her table in a red skirt, man’s striped shirt and big boots. These and other stories trace the vigour of young women’s determination to respond to the consumer possibilities of a spectacular new world of media images, electric light and postwar male uncertainties.

... (read more)Times & Tides: A Middle Harbour memoir by Gavin Souter

Near a little beach at Northbridge, in the heart of Sydney’s northern suburbs, the vertical rock face carries the image of a whale, about life-size, created by the original inhabitants at some indeterminate date. ‘[B]ecause of its precipitous location,’ says Gavin Souter, ‘one cannot stand far enough away to take it in all at once. Head, fins, flukes and flippers have to be viewed separately, then put together.’

... (read more)Professional Savages: Captive lives and Western spectacle by Roslyn Poignant

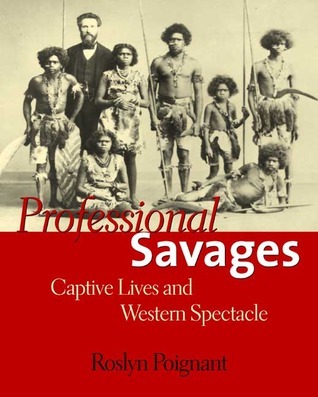

One photograph in this beautifully produced book is indelible. It is Paris, 1885, and against a painted show backdrop, Billy, young Toby and his mother pose with their boomerangs and a miniature dog. The disoriented, troubled eyes of these north Queenslanders look you right in the face. The sharp-focus dog, a taxidermist’s creation, paradoxically strikes a more animated stance than the living humans. This macabre depiction of people as ‘types’ led Roslyn Poignant to investigate an historical epic of dynamic performers.

... (read more)Childhood is a fertile territory for writers. Almost all first-time authors hoe it, and some continue to do so for the rest of their careers. Given the chance, most people cannot resist the impulse to reminisce about the horrors and delights of being a child.

... (read more)On Shaggy Ridge by Phillip Bradley & Kokoda by Peter FitzSimons

Of all the campaigns that took place in the western half of Australian New Guinea during World War II, Shaggy Ridge is among the most neglected. It does not deserve this status. There used to be a graphic, brooding diorama depicting the massiveness of the ridge in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra; unfortunately, it has been removed and replaced by other exhibits.

... (read more)What the hell is Bob Ellis? Discuss. Ellis might put it like this himself. Chances are he’s asked the question of a street window once or twice in wonderment and mock self-mockery. He’s earned it. From the back-cover blurbs down the years, one has got, by way of label, ‘l’enfant terrible of Australian culture’ (The Inessential Ellis, 1992), ‘a kind of dusty national icon’ (Goodbye Babylon, 2002) and now, in a disappointing regression to understatement, ‘a political backroomer’. We can assume, I think, that these are self-descriptions. Another, from the text of Goodbye Babylon, puts it this way:

... (read more)More Than a Game: The real story of the Australian Rules Football edited by Rob Hess and Bob Stewart

In his spirited foreword, well-known football writer Martin Flanagan notes that ‘More Than a Game is in the best traditions of Australian football writing. It is unauthorised, a necessary virtue given the blurring of the Australian media with the corporate interests behind football.’ Flanagan also knows that writing about football in Australia has become a dignified and scholarly pursuit. Still, football as representing the verities of life is a powerful and relatively new symbol. As the editors and contributors amply demonstrate, Australian Rules history has been measured out in tribal rivalries and violence. These two themes, along with many contemporary evaluations, are explored in detail.

... (read more)A New Britannia by Humphrey McQueen & Social Sketches of Australia by Humphrey McQueen

There must be few Australian history books that have run to a fourth edition, and it’s hard to think of any that have provoked as much discussion – and rancour – as Humphrey McQueen’s ‘New Left’ classic A New Britannia. It’s the Sergeant Pepper of Australian historiography: racy, emblematic of its time and place, and full of special effects – the impolite may call some of them recording tricks. Does it still have the capacity to shock the first-time reader, as it did me when I encountered it as an undergraduate in the 1980s? Perhaps, having been bred on so many of the legends to which McQueen laid waste, I was just very shockable. Like a lot of readers, I had never imagined Henry Lawson as a fascist.

... (read more)In 1989 John Mulvaney proposed that ‘the greatest gift of Aboriginal society to multicultural Australia’ was ‘a spiritual concept of place’. It was a momentous pronouncement, but two decades later both the statement and the gift itself need reassessment. If Mulvaney was right, then non-Aboriginal Australians enunciated their most precise and passionate concepts of place in the two decades after 1980. Yet ‘multicultural Australia’, that is, non-Anglo-Celtic Australians, didn’t really share the gift at all. Maybe they didn’t want it. Nor did the great gift of a spiritual concept of place come without cost to the indigenous people themselves. Today, newer forms of belonging are sometimes not concerned with Australia-specific land at all. Mulvaney’s observation, I conclude, is losing some of its force.

... (read more)