Australian History

A Nation At Last?: The changing character of Australian nationalism 1880–1988 by Stephen Alomes

The dilemma for confessedly nationalist intellectuals has always been what to do about their strange bed-fellows, the scoundrels who have sought a last refuge under the same patriotic blanket. Generally they have distanced themselves with glib distinctions between good and bad nationalisms, left and right nationalisms, radical and conservative and larrikin and respectable nationalisms. Often, too, they looked back – radicals to the 1890s, conservatives to the Great War – and contrasted an idealised past nationalism with contemporary selfishness. How often does discussion of Australian nationalism not get past the 1890s?

... (read more)A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900 by Andrew Roberts

It is such an obvious subject for a book. The two most powerful peoples in the world in the past thousand years have been the Chinese-speaking and the English-speaking peoples, and in the past hundred years those speaking English have been the more influential. While Winston Churchill wrote four volumes, which were bestsellers in their time, on the history of the English-speaking peoples up to the year 1901, I know of no other book which has surveyed this century of their greatest power.

... (read more)Inside the Welfare Lobby: A history of the Australian Council of Social Service by Philip Mendes

Most of you will have heard of the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS), but for those who have not, it is the peak lobby group of the community welfare sector. ACOSS’s website will tell you that its aims ‘are to reduce poverty and inequality by developing and promoting socially, economically and environmentally responsible public policy and action by government, community and business while supporting non-government organisations which provide assistance to vulnerable Australians’. ACOSS has seventy member organisations, including eight Councils of Social Service at state and territory level, and another four hundred associate members. Every year, Council of Social Service staff lobby federal, state and territory politicians and bureaucrats with proposals and budget submissions. And every year, bureaucrats and ministerial staffers craft careful speeches for politicians game enough to face the Council’s tough questions about budgetary allocations.

... (read more)The roll-call of Australian female singers of the past resounds like a comforting resurrection of anachronisms: Ada Crosley, Florence Austral, Gertrude Johnson and the epitome of stardom, Melba. The name Amy Castles represents another thing, as Jeff Brownrigg’s recent addition to the cultural history of early Australian songbirds attests. Born into a Catholic and unmusical background in Bendigo in 1880, she was destined to suffer a condition not unknown to musical novitiates: vastly more hype than talent or accomplishment.

... (read more)1001 Australians You Should Know edited by Toby Creswell and Samantha Trenoweth

Scheherazade, you have much to answer for! 1001 nights were fine for you, but by now there might well be that number of volumes offering that much advice about books, films and paintings, not to mention screen savers and blogs. So this bulky new book should be seen first, even primarily, as a marketing opportunity.

... (read more)Port Phillip Gentlemen: Good society in Melbourne before the gold rushes by Paul de Serville

One of the most interesting developments in recent Australian historiography has been a pushing back of the frontiers, a recovery of times or phases which seemed quite beyond recall, even when remembered. Such history-writing bears something of the character of sounding in archaeology.

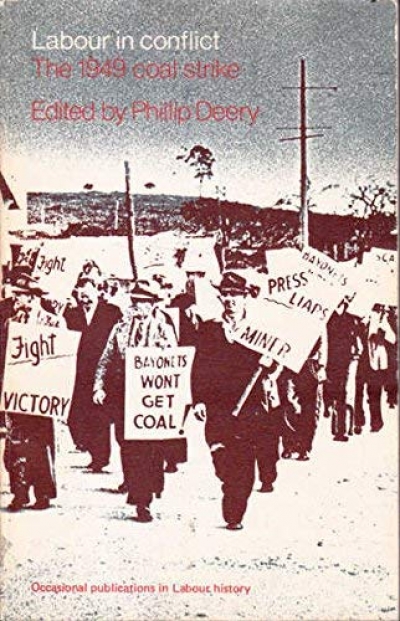

... (read more)Labour in Conflict: The 1949 coal strike edited by Phillip Deery

One of the great merits of Phillip Deery’s presentation is the way in which he shows the immediacy of the coal strike: its great significance in changing the lives of the miners and in transforming the political situation in New South Wales. It was a time of great bitterness, in which those who expected the interests of the Labor movement and the Labor Party to converge, considered themselves betrayed. Nor did the swiftness of the Chifley government in moving to crush the miners’ strike garner them any favour in the public’s eyes. The public considered the hardships brought about by the coal strike to be merely the latest in a series of events that seem destined to threaten their comfort and standard of living. The communists were blamed for the strike, probably unjustly, for although there were communists among the miners, the vast majority were non-communists with legitimate grievances against the mining companies.

... (read more)Jessie Street: A rewarding but unrewarded life by Peter Sekuless

Jessie Street, the subject of this biography, is one of the women we have ignored. She is an important figure in our history, but few people know much about her life. She was involved in feminist and socialist movements, in the Labor Party, in campaigns for Aboriginal rights and in the movement for world peace – in a long active career which spanned the years 1911–70.

... (read more)Veiled Valour: Australian Special Forces in Afghanistan and war crimes allegations by Tom Frame

Almost fifteen years ago, struck by the paucity of information in the media about the ADF deployment to Afghanistan, I edited a short collection of essays that posed a modest question: What are we doing in Afghanistan? (2009). I wish I had known then half of what Tom Frame reveals about the ADF’s activities in Central Asia in his new book, Veiled Valour.

... (read more)The Unforgiving Rope: Murder and hanging on Australia's western frontier by Simon Adams

Simon Adams’s thesis is that capital punishment was crucial in how the West was won: ‘The gallows were a potent symbol of an unforgiving social order that was determined to stamp its moral authority over one-third of the Australian continent.’ But hanging was discriminatory; it ‘was never applied fairly or impartially in Western Australia’. Adams points to the fact that ‘there were 17 men hanged between 1889 and 1904, all of whom were “foreigners”: two Afghans, six Chinese, one Malay, two Indians, one Greek, one Frenchman and four Manilamen’, but not a single ‘Britisher’. Capital punishment was racist, reflecting the ‘distortions and prejudices of the British colonial legal system’.

... (read more)