Biography

Quentin Bryce: The authorised biography by Juliet Rieden

Considering the number of biographies published about distinguished Australian women in the past few years, we have had to wait a surprisingly long time to read the life story of Quentin Bryce, Australia’s first woman governor-general. Certainly, her achievements merit a full biography: she has been a lifelong advocate for women and children, one of the first women barristers in Queensland, a prominent member of the National Women’s Advisory Council (NWAC), Federal Sex Discrimination Commissioner, CEO of the National Childcare Accreditation Council, principal of the Women’s College at the University of Sydney, and governor of Queensland. She was not satisfied with carrying out a purely ceremonial role as governor-general either, making comments that suggested she supported an Australian republic and same-sex marriage.

... (read more)Gough Whitlam: The vista of the new by Troy Bramston

Troy Bramston is fast becoming the Peter FitzSimons of Australian political biography. Every few years a door-stopping volume on a prime minister appears, brandishing the same formula of ‘never before seen’ documents and ‘fresh revelations’. In the Acknowledgements to this latest biography of Gough Whitlam, Bramston virtually pleads with readers to render homage to the ‘hundreds’ of interviews he conducted, the ‘thousands’ of pages turned in archives, the miles clocked in libraries visited. There is a diligent busyness to the enterprise. But Bramston’s relentless emphasis on the quantitative smothers his underlying inability to master the material. The result, sadly, is an incomplete picture of Whitlam: a workman-like chronicle of the life, but not a deep exploration of the political and intellectual dimensions of the man.

... (read more)This week on The ABR Podcast, we feature a special essay by biographer Nadia Wheatley titled ‘Liars, inventors, embroiderers: Rewriting the life and myth of Charmian Clift’.

... (read more)What does a biographer do when she discovers she has something wrong? I am not talking about a misinterpretation, but missing a great big whopping fact …

In this case, the new information did not concern my subject directly, but her mother. Nevertheless, it has caused me to rewrite parts of both the life and the myth of Charmian Clift.

... (read more)Walter Lippmann: An intellectual biography by Tom Arnold-Forster

Walter Lippmann might be the defining example of a public intellectual. He profoundly influenced public and political debate in America during the twentieth century. A prolific journalist and columnist, he also published ten major books and even more edited collections and compilations. The best of these were thought-provoking disquisitions on public opinion, communications, politics, international relations, and the ways in which liberal thought has developed in the United States. His was, argues Tom Arnold-Forster, ‘a six-decade commentary on the vicissitudes of politics’.

... (read more)This week, on The ABR Podcast, Patrick Mullins reviews Hawke PM: The making of a legend by David Day. Approaching Day’s second volume of the Hawke biography, Mullins asks: ‘how much more can there be to say?’

... (read more)There is a fine tradition in Australia of two-volume prime ministerial biographies. John La Nauze on Alfred Deakin (1965), Laurie Fitzhardinge on Billy Hughes (1964, 1979), John Edwards on John Curtin (2017, 2018), Allan Martin on Robert Menzies (1993, 1999), Jenny Hocking on Gough Whitlam (2009, 2012): all are insightful and enduring accounts of significant figures who exerted deep influence on the country.

... (read more)Defiance: Stories from nature and its defenders by Bob Brown

In a dark age on a burning planet, radical hope is not an easy assignment, but every decade or thereabouts, Bob Brown invites Australians to give it a crack. His Memo for a Saner World (2004) was followed by Optimism (2014), and his new release, Defiance, opens as a redux of both, with the cinematic story of the environmental campaign that changed Australia’s political contours.

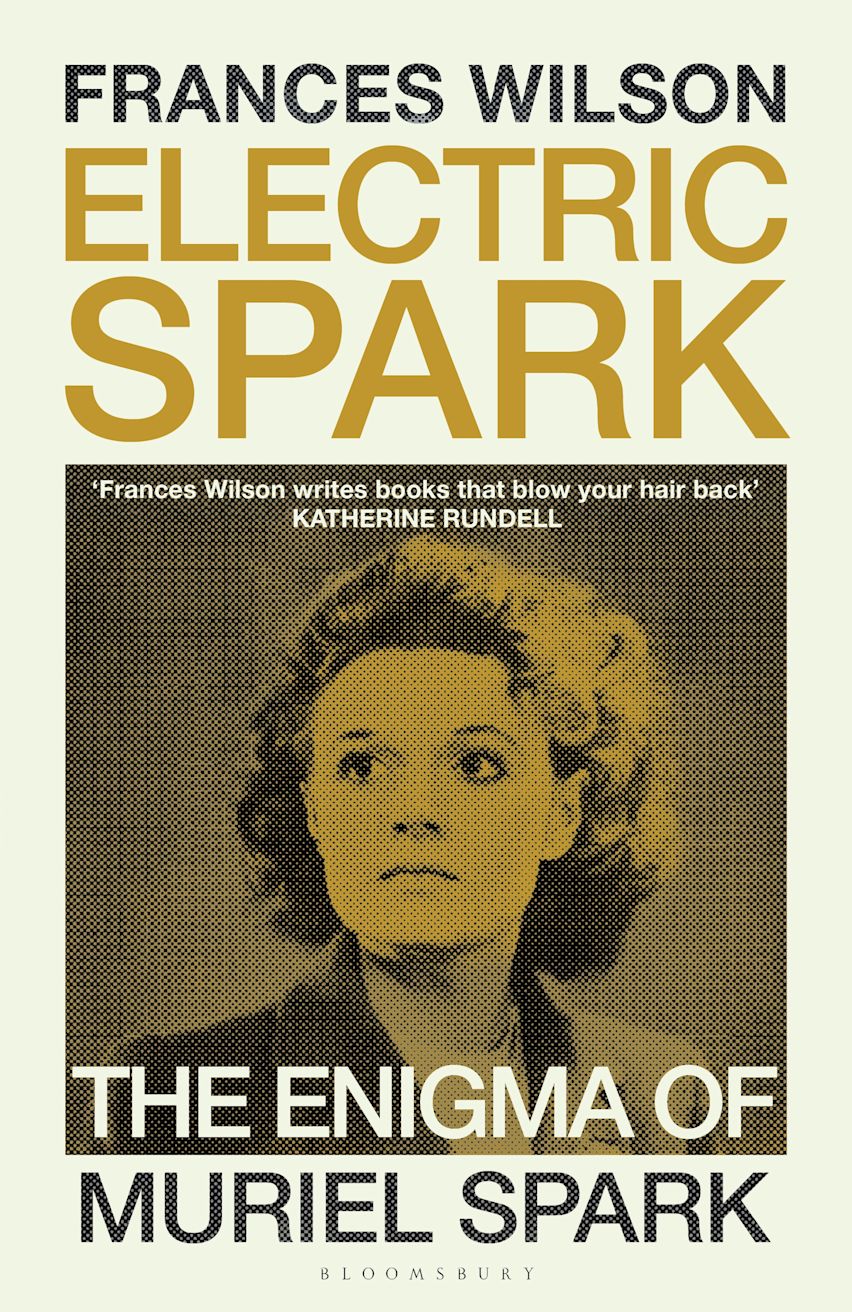

... (read more)Some literary biographies are best known for their gestation – or malgestation. Some authors, we might go further, should have a big sign around their neck – noli me tangere. Muriel Spark is one of them. Her voluminous archive, lovingly tended all her life, is full of booby traps. Twice she went into battle with biographers: first Derek Stanford, a former lover; then Martin Stannard, whose biography of Evelyn Waugh she had admired.

... (read more)The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath by Sylvia Plath, edited by Peter K. Steinberg & Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark

For seven years after her 1963 burial, Sylvia Plath lay in an unmarked grave near St Thomas the Apostle Church in Heptonstall, West Yorkshire. The gravestone, when it came, bore her birth and married names, Sylvia Plath Hughes, the years of her birth and death, and a line from Wu Cheng-en’s sixteenth-century novel Monkey King:Journey to the West: ‘Even amidst fierce flames, the golden lotus can be planted.’

... (read more)