Biography

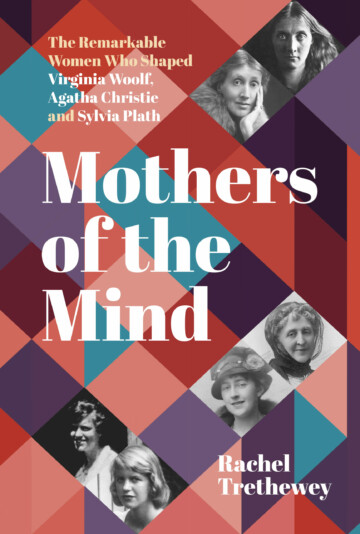

Mothers of the Mind: The remarkable women who shaped Virginia Woolf, Agatha Christie and Sylvia Plath by Rachel Trethewey

Reading for this review I came across some apposite words by Jacqueline Rose, biographer of Sylvia Plath, cultural analyst and explorer of the lives and roles of women:

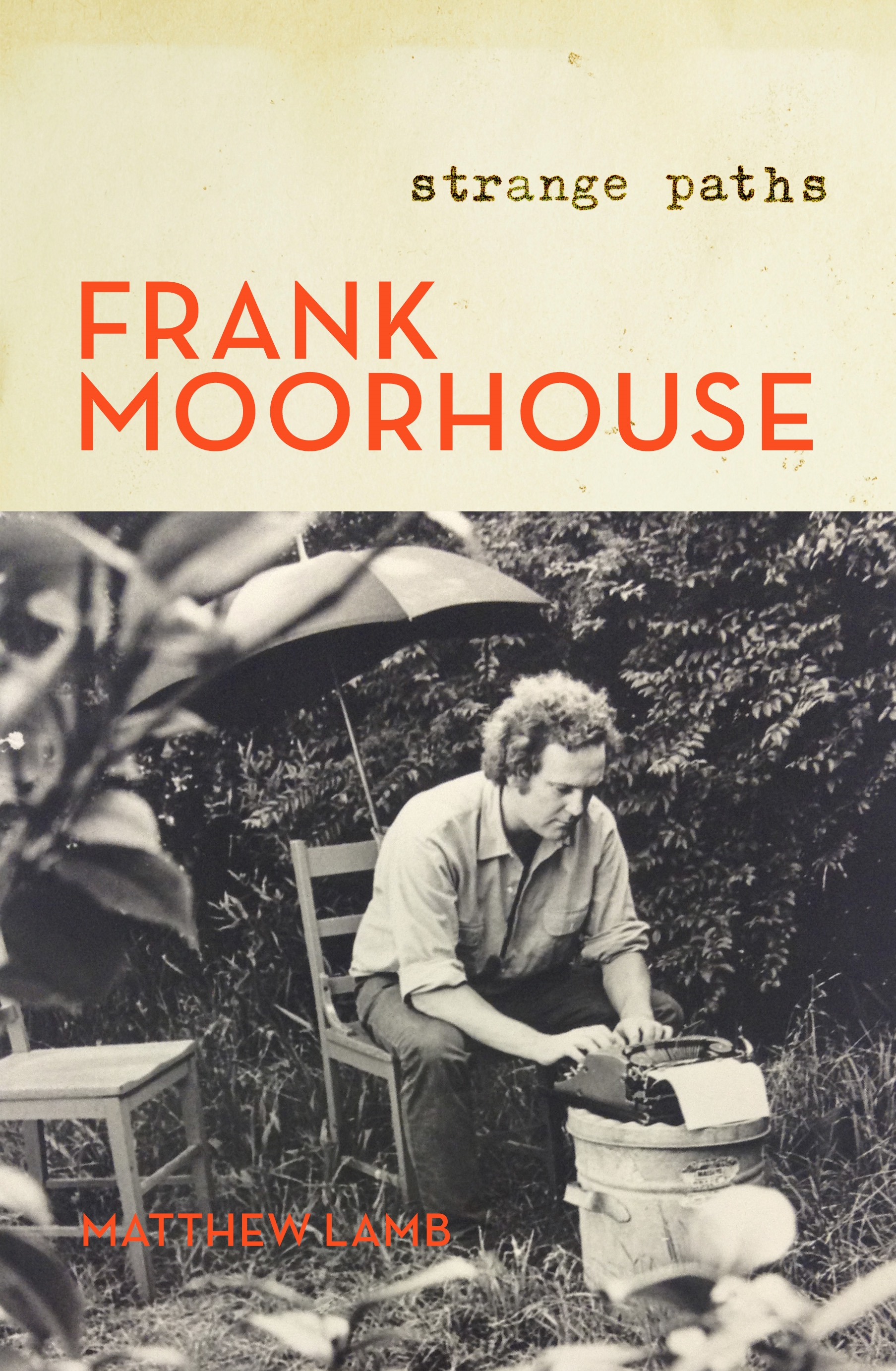

... (read more)Frank Moorhouse: Strange paths has no introduction, but Matthew Lamb describes it in his author’s note as ‘the first in a projected two-volume cultural biography of Frank Moorhouse’, covering the long writing apprenticeship of 1938–74 during which Moorhouse ‘br[oke] into the literary establishment, on his own terms’. Lamb does not explain his use of the term ‘cultural biography’ within the book, but the term is apt to describe how ‘biography intersects with social history’ as the book tracks Moorhouse’s ‘negotiation of shifting social conventions and historical moments’ (as Lamb puts it in an article on the Penguin website titled ‘“When the facts conflict with the legend” – How does a biographer balance storytelling with the truth?’).

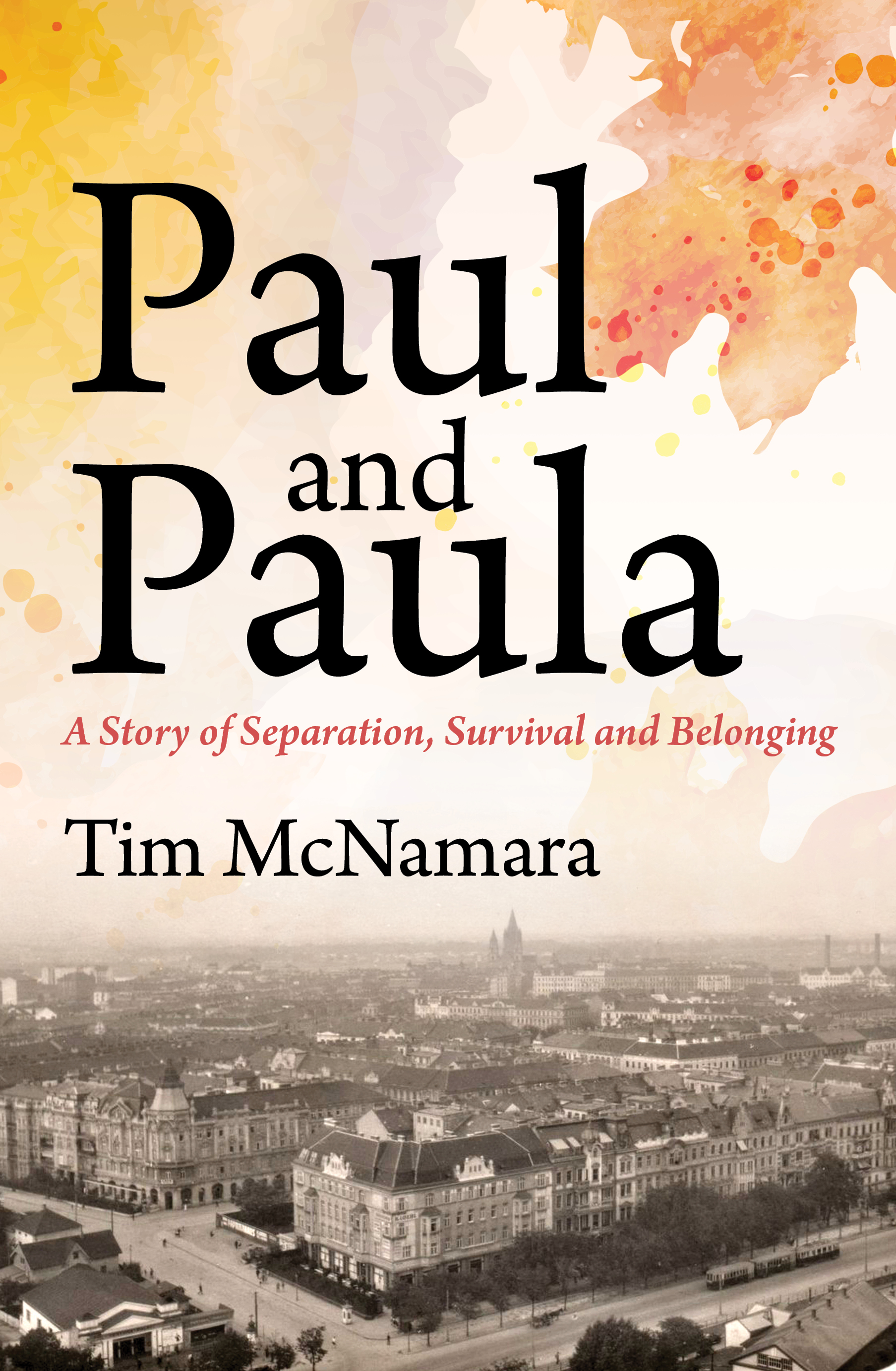

... (read more)Paul and Paula: A history of separation, survival and belonging by Tim McNamara

In Working: Researching, interviewing, writing, published in 2019, the great biographer Robert A. Caro tells of his writing methods and the lengths to which he goes to gain a better understanding of his subject. Reading Tim McNamara’s Paul and Paula, I was reminded of Caro’s way of research and writing and of his determination to place himself in his subject’s milieu. McNamara spent considerable time in Vienna researching Paul and Paula, stalking the streets for clues, and his efforts show. He writes with verve about the book’s three main characters – Paul Kurz and his wife, Paula, and the city of Vienna, before and during the Nazi occupation – and his search to uncover and understand their stories.

... (read more)It was mid-afternoon when I turned a typewritten foolscap page from 1939 and found the name I had been searching for: Detective Sergeant Mischenko. The report was a pretty banal cry for resourcing. Poor Mischenko was doing the work of two detectives in Japanese-occupied Shanghai and desperately needed some assistance. On turning the page, I felt like Archimedes himself (though running through the US National Archives yelling ‘Eureka!’ might have been a touch dramatic). My journey to the suburbs in the middle of a clammy Washington DC summer had held no guarantees of finding this.

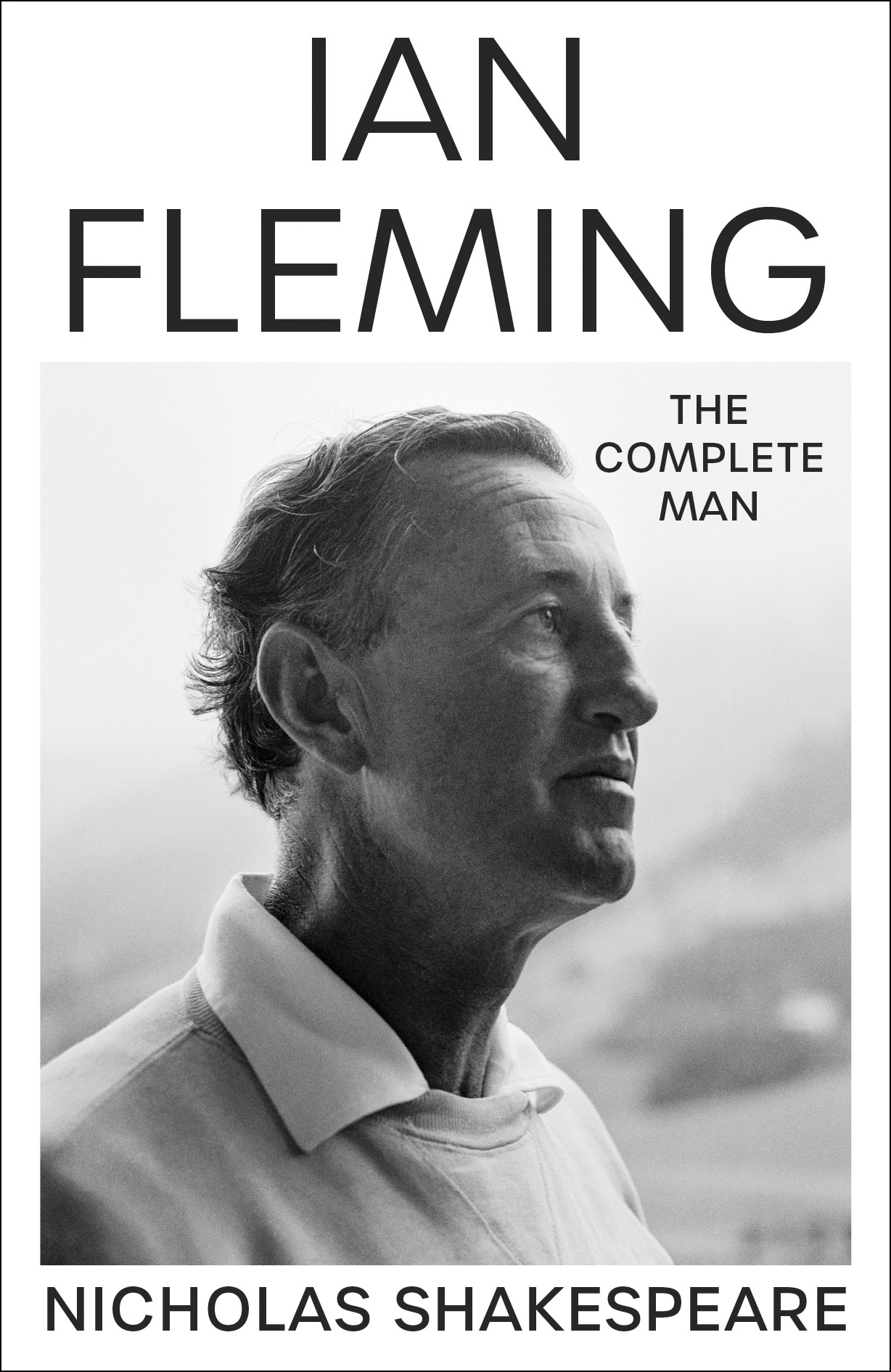

... (read more)Ian Fleming: The complete man by Nicholas Shakespeare

The smallest, dullest link in the fateful chain binding John F. Kennedy and his assassin Lee Harvey Oswald is that both men were big fans of the fictional spy James Bond. In the immediate aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, when investigators searched the tiny boarding room in Dallas that Oswald rented for $8 per week, they found the four Bond books that citizen Oswald had assiduously borrowed from a local library.

One of these was From Russia with Love, Ian Fleming’s novel from 1957, which has at its heart the cat-and-mouse relationship between Bond and the crack SMERSH assassin Donovan Grant, who is tasked and determined to take out Bond, and with him the agency he represents.

... (read more)The death of Gabrielle Carey earlier this year was a cruel loss for the Australian literary world, especially its Joyce community. I first met Gabrielle shortly after moving to Sydney from London in 2010. She invited me to her annual Bloomsday celebration, which took place in a Glebe pub. I was new in town and delighted to join the readings and revelry. I suspected, rightly, that my Dublin accent would glean me some credibility, if nothing else did.

... (read more)Bennelong & Phillip: A history unravelled by Kate Fullagar

The story of the extended encounter between Eora Aboriginal man Bennelong and Arthur Phillip, first governor of the British colony at Sydney, has often been told as both emblematic and predictive of the history of British possession of Australia, and of Aboriginal dispossession. Historians such as Grace Karskens and Keith Vincent Smith have peeled back the layers of this narrative to find ways of telling more complex, contextualised, and open-ended stories. Fullagar reaches a new stage in this journey, and the journey of Australian history more generally. She offers a fresh perspective on Bennelong and Phillip, on the nature of their exchange and the broader currents in which they swam.

... (read more)In Michael Wolff’s telling, the final stretch of Rupert Murdoch’s seventy-year media career plays out like a ghost story. When, in 2016, Rupert’s sons, Lachlan and James, vanquished Roger Ailes – disgraced architect of Fox News – in a rare moment of fraternal unity, the money-printing reactionary machine Ailes had built for their father kept on mutating and metastasising, in ways that would haunt the company and the Murdoch family. Fresh from writing a blockbuster trilogy documenting the Trump presidency, in The Fall Wolff braves the ‘nest of vipers’ that is the late-stage Fox News empire with a deep contact list and a strong stomach. Gone is the rare access to Rupert himself that informed The Man Who Owns The News (2008), but, fortunately for Wolff and his readers, the largely unnamed vipers of The Fall are a chatty bunch.

... (read more)Nick Drake’s ‘Fruit Tree’, one of his best-known songs, addresses the idea that even if an artist is ignored in their lifetime, their legacy can be secured, and their work imortalised, with an early death. The song, as we learn from Richard Morton Jack’s exhaustive biography of the English singer-songwriter, was partly inspired by the precocious English boy poet Thomas Chatterton, who committed suicide at the age of seventeen, in 1770.

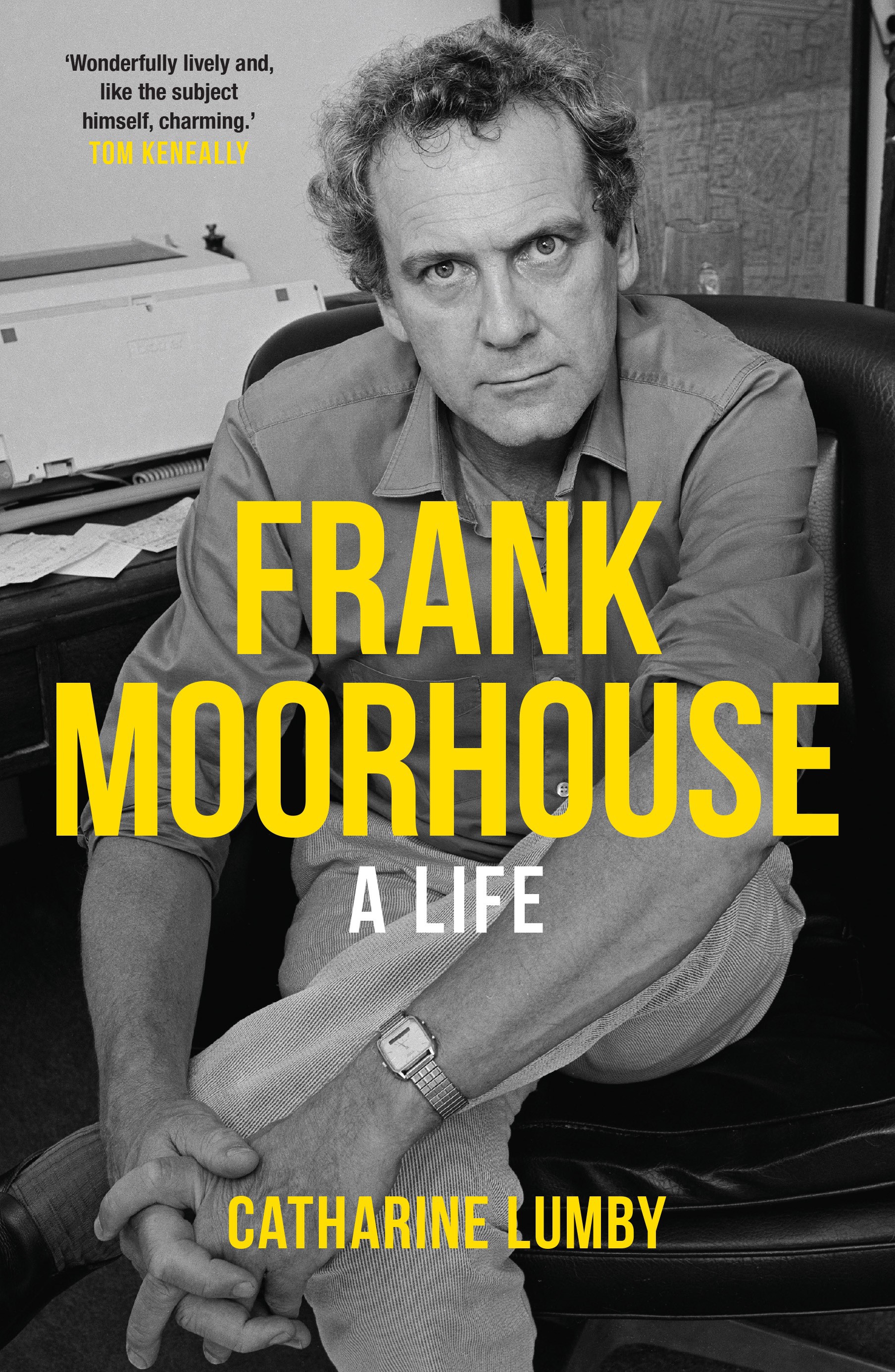

... (read more)Near the end of this biography of Frank Moorhouse, author Catharine Lumby tells a story that will strike retrospective fear into the heart of any male reader who has ever climbed a tree. Watching an outdoor ceremony in which a cohort of Cub Scouts was being initiated into the Boy Scout troop to which he belonged himself, and having climbed a tree to get a better view, the young Moorhouse ‘slipped, and he slid a couple of metres down the trunk of the tree with his legs wrapped around it. He came to rest on a jagged branch, his crotch caught in the fork.’

... (read more)