History

Racers of the Deep: The Yankee Clippers and Bluenose Clippers on the Australian Run 1852 - 1869 by Ralph P. Neale

In the years before steamships gained supremacy of the oceans, sailing ships became faster and were able, for two decades, to outrun the primitive new technology. This book concentrates on the clippers built in North America and used on the run from Liverpool to Melbourne during this period.

... (read more)In the Name of the Law: William Willshire and the Policing of the Australian Frontier by Amanda Nettelbeck and Robert Foster

William Willshire was Officer in Charge of the Native Police in Central Australia from 1884 to 1891, when he was charged with the murder of two Aborigines. He was acquitted, but was regarded by his superiors from then on as something of a liability, ending his career in an uneventful posting in Cowell on the Yorke Peninsula. He wrote three books about his life as an outback hero, glorifying himself as an anthropologist and sentimental champion of the people he had policed with ignorant brutality.

... (read more)Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA by Tim Weiner

Of the many damning revelations contained in this book, the fact that Allan Dulles, the CIA’s longest serving director (1953–61), would assess the merits of intelligence briefings by their weight is among the most startling. Coming in at 700 pages, Tim Weiner’s Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA is sufficiently hefty to have commanded Dulles’s attention. Were he alive today to read this searing indictment of the institution he did so much to construct, however, it is doubtful that Dulles would find much cause for cheer.

... (read more)Designing Australia's Cities: Culture, commerce, and the city beautiful 1900–1930 by Robert Freestone

The planning history of our cities is one that has received surprisingly little attention. While the catalogue abounds in detailed studies – Adelaide and Canberra between them account for the bulk of this literature – national overviews, much less international contexts, are thin on the ground. In this rarefied atmosphere, Robert Freestone has been a generous contributor. His earlier Model Communities: The Garden City movement in Australia (1989) provided a comprehensive overview of urban planning in the period here under review (1900–30). Designing Australian Cities now provides a complementary overlay.

... (read more)Man of Steel: A Cartoon history of the Howard years edited by Russ Radcliffe

If you look carefully at a political cartoon, the most remarkable thing is the quantity of latent information it depends on. Opening Russ Radcliffe’s collection from the Howard years at random, I spot something from one of the nation’s less fabled cartoonists, Vince O’Farrell of the Illawarra Mercury. It is a picture of a military aircraft marked Labor, barrelling along the ground. The pilot has a pointy nose and broad girth, and the co-pilot’s voice bubble tells us, ‘I say skipper … That’s the end of the runway and we still haven’t taken off’. The whole story of Bomber Beazley’s last, tortured term as Opposition leader is there in an image and a couple of words that takes only seconds to assimilate.

... (read more)Nature as Model: Salomon De Caus and early seventeenth century landscape design by Luke Morgan

In the early seventeenth century, the German princely territory of the Palatinate burst on to the centre of the European political stage. In August 1619 the Elector Palatine Frederick V – ruler of one of the most prosperous and culturally vibrant territories of the Holy Roman Empire, and a leader of Protestants throughout Europe – was elected king of Bohemia. This put him in opposition to the newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, an Austrian Hapsburg and leader of the Catholic forces, who had been deposed a year earlier by the same rebellious Bohemian estates which then elected Frederick. These events quickly fuelled what has come to be known as the Thirty Years War (1618–48), one of the most ferocious in Europe’s bloody history.

... (read more)The Enlightenment and the Book: Scottish authors and their publishers in eighteenth-century Britain, Ireland and America by Richard B. Sher

The Enlightenment gave birth to our modern world. Within this broad movement, spread over many countries, the contribution of Scotland was of pre-eminent importance. We all know the names of Adam Smith and David Hume, and we recognise their influence today, but how did their ideas get out into the wider world? Of course, there were books, Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40) and Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) amongst the best known. But where were their books published? Who printed them? Who published them? How were they marketed? These are questions which we have probably never posed to ourselves, but they are vital to our understanding of how writers from a small country on the edge of Europe came to play such an important part in this international movement. As Richard B. Sher points out, we know the writers but we don’t know the publishers and printers without whom their books would never have reached the public. In this book he sets out, amongst other things, to redress the balance.

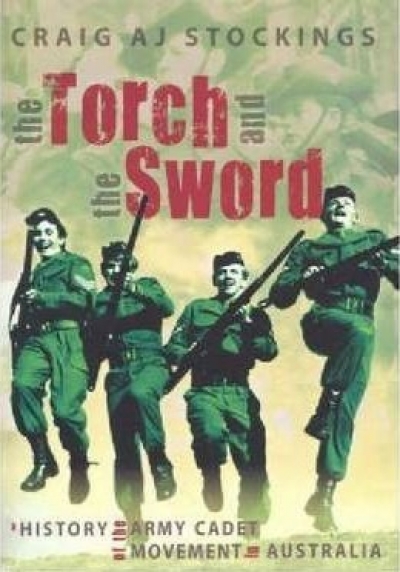

... (read more)The Torch and the Sword: A history of the army cadet movement in Australia by Craig A.J. Stockings

The Torch and the Sword began life as Craig Stockings’s PhD thesis, and shows its origins on every page. He presents a hypothesis and refers to it often as he proceeds systematically through a chronological and thematic exposition of his subject.

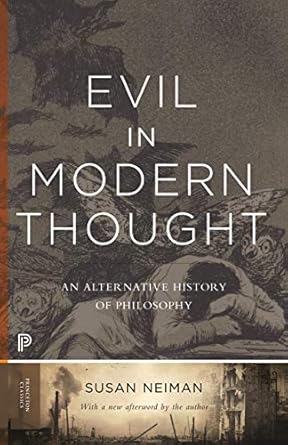

... (read more)Evil in Modern Thought: An alternative history of philosophy by Susan Neiman

Late in in the thirteenth century, Alfonso X (‘The Wise’), king of Castille, declared: ‘If I had been of God’s counsel at the Creation, many things would have been ordered better.’ He raised a storm. That wickedness, natural disaster and the inexorable corruption of things filled the world with suffering had hardly gone unnoticed, of course. Theologians had long sought to reconcile the existence of evil with God’s omnipotence and benevolence. But Alfonso reanimated a worm in the heart of reason: the suspicion that, really, God could have done better.

... (read more)The official published accounts of Captain Cook’s three great voyages (1768-79) were immense popular successes in Britain. That for the third voyage sold out within three days of publication in 1784. When the Frenchman La Pérouse sailed from Botany Bay in March 1788 into the Pacific – and into oblivion – he remarked that Cook had done so much that he had left him nothing to do but admire his work. In the previous year, the German, Georg Forster, had published in Berlin his eulogy of Cook, Cook der Entdecker (Cook the Discoverer). Cook was the first international superstar, and time has only increased his celebrity status. Major scholarly biographies continue to be published, and seminars which feature Cook in their titles are sell-outs. The name is box-office magic.

... (read more)